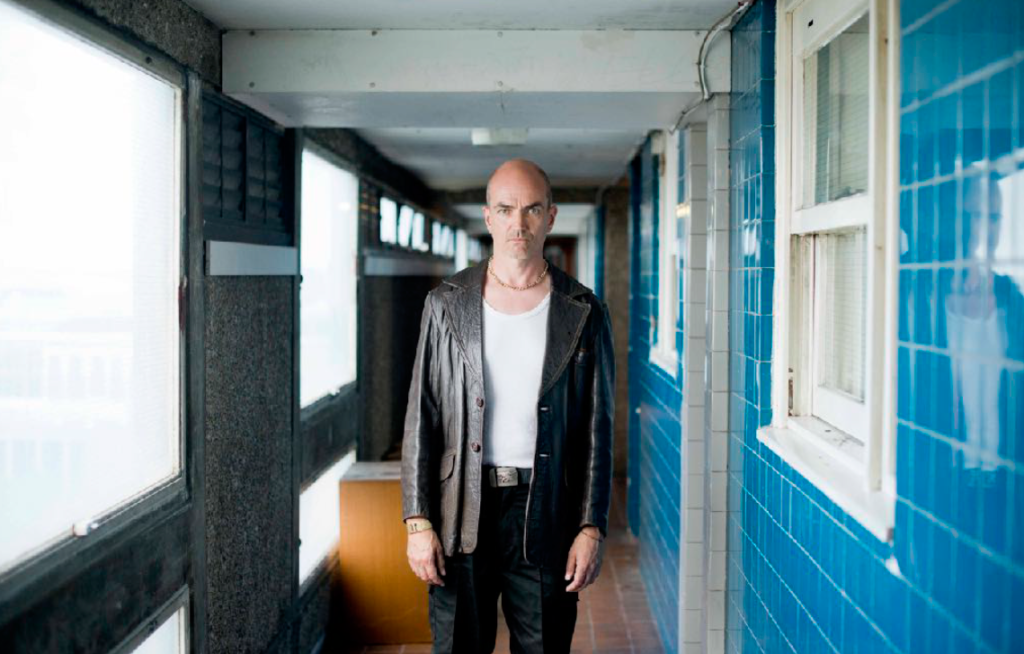

Felix Mortimer is a former member of Punchdrunk who has gone on to found RETZ with Simon Ryninks to respond to the need for a dialogue between performance, film and the internet. Felix has produced and directed many large-scale site-specific, technology-led performance projects. Felix has also worked for BBC Radio Drama, Punchdrunk, The Royal Court, The Old Vic and The Bernie Grant Arts Centre and is a fully qualified teacher. RETZ performed an experimental version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest called O Brave New World, which took place over six months and across the physical and online worlds. To read PART I of this article, click here.

Adapting Franz Kafka’s the trial

For our piece The Trial, we decided to adapt two Franz Kafka stories, The Trial, the seminal novel about being stuck in bureaucracy which you can’t escape rife with paranoia and desolation. In The Penal Colony: a short story about the officer of a penal colony who invents a device that inscribes a person’s crimes on their skin before killing them and eventual himself. Cheery.

Adapting to now

Our challenge was not only to adapt these two stories into 2013 but also to adapt them across six locations in East London.

This was the first production we had set in London so we had to first begin to modernise the 100-year-old text.

The piece became about the pervasive power of the internet, we recast the machine of in the penal colony as the panopticon of the world wide web, able to see all actions and anticipate crimes.

We re-wrote the source material almost entirely, transposing it into our locations. We broke the original stories down into key sections, adapting them both to cast the audience member as the desperate Joseph K. figure, following fruitlessly a character actually called “Joseph K,” deeper down the rabbit hole of narrative that we created.

We also had to adapt to multiple locations:

Loosely the story became:

The audience member reaching Shoreditch Town Hall, imagining they were seeing a play, being ushered into the basement where they stumbled across a variety of material about Joseph K.; an alarm was set off and they were evacuated outside.

Outside on the street, a police officer approached them and arrested them for wandering into a restricted area. He instructed them to travel up the street to visit a lawyer.

They journeyed up the street to the accompaniment of the lawyers answer phone which they were instructed to call the police.

Upon reaching the lawyer’s office they met his secretary, who quizzed them on their ‘crimes,’ the lawyer revealed that they were scheduled to be executed at the Department for Digital Privacy and given time to attend.

They were then met by a woman who had something to show them, in a garage out back “Joseph K.” was cowering. As you spent some time alone with him two thugs joined you and killed him in front of you as you escaped a man leaving a nearby church scooped you up and using a priestly voice told you a story of the futility of the law.

This structure took scenes from Kafka’s novel and replaced them, characters remained but situations changed.

Building a network

Rehearsal Process

We rehearsed and wrote this piece in the preceding two months. We had written all the dialogue and rehearsed with long chunks for the actors to memorise. Very quickly into the rehearsal process, it became apparent that as the audience members were not present in the rehearsal process it meant we were missing a key actor in the narrative. We tore up the scripts and instead gave the actors plot points to hit and a place to psychologically deliver the audience member at the end of their five-minute section. This process led to a more rewarding experience for each audience member as actors improvised around their environments and characters created a fresh performance for each of the three thousand audience members that ventured into their company for their five-minute scenes.

This enabled even the most passive audience members to be brought out of their shells and disruptive audience members being subdued by the flicker of an eyebrow.

Timings and curating the second half

The rehearsal process for the second half which took place in the Department for Digital Privacy was radically different but built on the principles of the first half, in the second half me and the dramaturg, Alex Crampton, gave the actors far more freedom to explore. We built two sets of five rooms, each to be contained by an actor, reflecting the first half. Each actor was given five minutes with the audience member, and became increasingly bizarre as they got closer to “the machine.”

The first room a caretaker told you a story about someone else who had been executed, then you were shown your picture haplessly searching for the lawyers office and quizzed about your personal life, then you were ushered into a “lawyer’s office” lined with books, where you were told your rights had been completely withdrawn, then a silent room where your last supper is offered, and finally a ritual of cleansing in the now almost darkness. This twenty-five minutes improvised section was designed to prepare you slowly for your inevitable death.

The extension of the plot points of the first half came with successes and failures, actors who felt comfortable improvising and building up characters succeed in giving this section the gravity that it needed, others failed and filled these sections with exposition distracting from the thrust of the piece.

Externally curated pieces

We chose to work with learning-disabled theatre company Access All Areas to curate the very beginning of the second half of The Trial, we wanted to suggest an alternate world, one which was strange yet familiar and Access All Areas are well respected for their unpretentious and direct approach. We tasked them with creating a reception and processing the audience members in as bizarre and anarchic way possible. Many of them pooled on their experiences of the benefits system and created characters who revelled in the meaninglessness of stamping, interviewing, signing and organising. These characters again grew backstories and interactions, we enabled a narrative universe where our actors could play and exist for hours on end.

The Trial was never going to directly emulate Kafka’s book, but like all adaptations, it was designed to channel the feeling of paranoia, claustrophobia and helplessness. Casting the audience member as the protagonist enabled us to build an intensity of feeling which was almost overwhelmed some. In one instance an audience member, upon being arrested ran down the road and had to be retrieved by a stage manager, the experience had triggered a hostage situation he had been in, but he returned to the performance again and said it was remarkably cathartic to live through these events in a safe environment.

The Trial saw us spread a universe through the streets of east London across two hours not six months. We experimented with journeys through the real world and capsules of content all of which fed into our largest project to date, Macbeth, across 12 hours and one monolithic tower.

Macbeth

As soon as you see the Balfron Tower in Poplar as you storm down the A12 motorway which cuts through the Lea Valley in east London it’s profile never leaves you. Defying logic architect, Erno Goldfinger created a silhouette of two towers, one unnervingly thin, one flat and expansive both connected by corridors suspended in midair. Goldfinger lived at Balfron Tower in Flat 101 for six months when it first opened and used this time to design Balfron’s sister Trellick in West London with almost no changes in design.

Standing at 27 stories, in 1956, this tower represented a revolution, soon to be joined by the Blackwall tunnel these post-war architectural pieces of utility-inspired JG Ballard’s novels Crash and High-Rise heralding an age of steel, concrete and social engineering. The millennium was still a life time away.

Balfron Tower and it’s neighbours became a byword in the 1980s and 1990s for urban poverty and decay, unloved communities, pirate radio and rap videos. Balfron welded itself into popular consciousness in Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and residents were painfully aware of the negative connotations of the ‘community in the sky’ where they lived.

When I was asked by the housing association that owned the building to pitch a performance to take place within it, I wandered through the dusty carpark, into the coffin-shaped lifts, over the gravity defying corridors and into the very human flats hewn into the concrete. Overlooked by the glass and pomp of Canary Wharf, London’s financial centre. Comparatively this 27-floor feast of a residential utopia that never was stands stark, a reminder, a blight on the landscape, a symbol of the utilitarian necessity after the second world war. Unapologetically aggressive. A project to change society for the better by an architect who did not compromise and lent his name to a bond villain.

Standing on that balcony thinking through the prison of our 1970s communist frame, I decided that Shakespeare’s Macbeth had the right bombast, fury and aggression to match our setting.

With that decided the epic responsibility of adapting Shakespeare’s darkest tragedy-laden with marital regicide, witchcraft and a full blown war was on us.

We decided quite quickly to set the action over one night and to perform it in real time over the same period. Descriptions of the night pepper the script and the plot and aftermath of the death of Duncan are enacted so quickly that to stage them across the evening culminating with Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking was a natural choice. We wanted to infect audiences members dreams as they slept in the spaces that had been stalked through by characters.

Come, thick night, / And pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell, / That my keen knife see not the wound it makes, / Nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark, / To cry “Hold, hold!”

“you secret, black, and midnight hags!”

We decided to stretch Macbeth over twelve hours, allowing times for audience to pause, consider, reflect, react and interact. This, of course, meant we also had to feed and accommodate them over night.

Role of the Audience

We made the decision to cast them as visitors to Macbeth’s Castle much like Duncan is at the beginning of the play. The witches scene took place in an underground car park under the Tower, with Macbeth and Banquo arriving in a 1950s jeep followed by Ross on a motorbike. The first scene over the cauldron became a summoning of the audience into the action itself.

Making it possible

It was our intention to make the piece feel like it was happening in the tower at the time when the audience were watching. We wanted to create a frenetic energy which allowed them to get swept up in the play.

We devised a complex stage management system which allowed us to have ten productions of Macbeth running concurrently. We cast three Macbeths, three Banquos, three Lady Macbeths and Lady Macduffs, all the other characters were staggered through the piece with audiences starting at ten minute intervals. This created a complex series of demands for our audiences and actors as they were strictly timetabled to perform the piece to all the different audience groups. It allowed actors to perform the same scenes ten times in repetition, interacting with different actors and different audience groups each time. Scenes were timed to the second and fitted together in a giant spreadsheet, stage managers and the guides in the rooms with audiences were tasked with keeping to the strict timings to ensure that for the audience scenes were flowing majestically into one another. The corridor off which the 10 flats were located was buzzing with actors storming their way in and out of flats, Lady Macbeth emerging in a nightgown at one end while not having even committed murder at the other.

Audiences came together with other groups for meals, for which we built two restaurants, and at the end of the play for the battle between Macbeth and Macduff on the roof of the building and a party to celebrate the victory of Malcolm.

For the first two performances, I was rushing around fixing TVs, desperately trying to get timings in line and sometimes failing miserably: actors ran into each other, didn’t know where they were going and popped up late or into the wrong scenes.

But by the third performance, a miracle happened, timings began to work, the legion of stage managers kept their scenes to 4:04 or 7:09 and got their audiences to the other side of a mammoth building (sometimes up or down 20 flights of stairs) in time. They built a narrative around these journeys and became the glue that bound the universe together.

I would stand in a stairwell and watch a group of the audience leave the elevator at the same time a Macbeth ran past, at the same time a witch descended from the ceiling, it became a stage management symphony. Why is this important dramaturgically? Because these chance encounters and journeys that bound the play together offered chaotic room for improvisation, allowed the audience to breath and understand the performance as it roared around them. It also gave the impression of action swirling around the scenes being played out: a distant conversation being enacted, a far off shriek, a group of people huddling on a landing. The narrative universe was alive and well and organically growing within the structure we had proscribed: backstories, dance routines, interconnections and interactions were growing and lending an energy of creativity.

Structured additions

Of course to stretch the play from 8pm – 8am we had to structure several additions to the narrative, building on our experience adapting The Tempest we wanted to add depth to previously under-explored characters allow the audience a chance to revisit the narrative. Expanding the experience from the Shakespearean words, bridging between the improvisation of the guides and more minor characters and the overarching narrative of the production. Allowing a different perspective on characters and situations seen, or about to be seen.

We commissioned writer Thomas McMullan and the actors playing the witches to create an investigation into that role. He wrote a piece which built on their backstories and created a chance for interaction with the audience. The witches brought a group of the audience into their flats, sat them down on cushions all together and created a seance-like atmosphere, asking the audience how they had arrived and when was the last time they came. In smaller groups, they were told a story which riffed on the historic marginalisation of women. His piece revolved around an incident which had unfolded in this flat which had led to the escape of the witch character and then her discovery of the flat again.

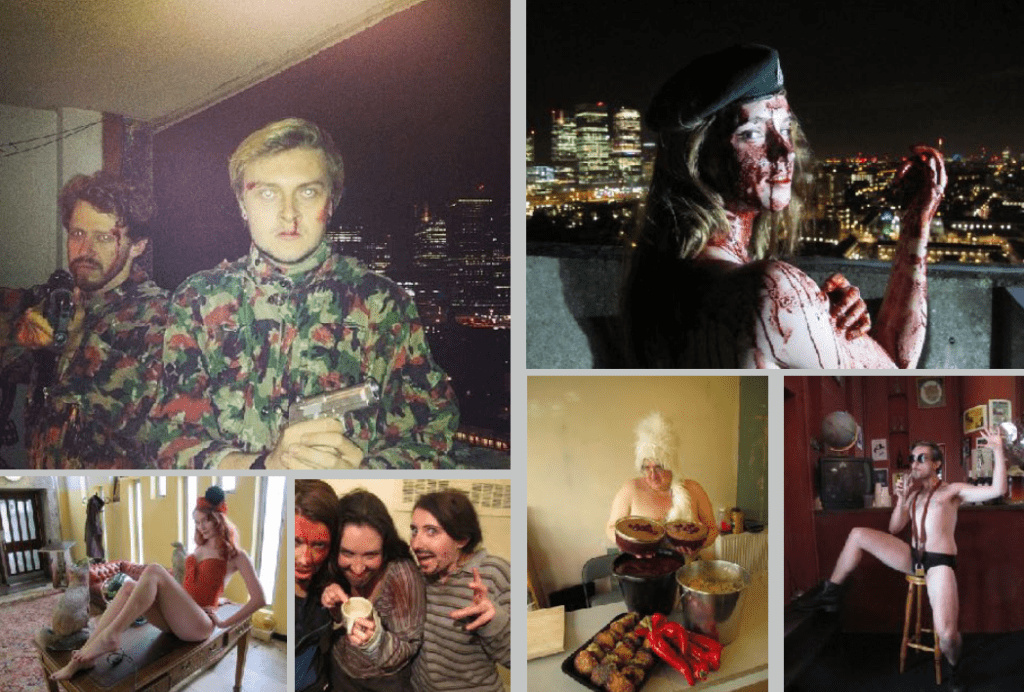

Similarly, we also worked with grotesque ensemble Gruff expand the characters of the murderers. These shady types have very few lines but enact much of Macbeth’s dirty work as he spirals into madness. The murderers are traditionally brutes or spies. Our murderers became Macbeth’s bastard children, four of them psychotic siblings, obsessed with the family unit and subverting it, brutally throwing Lady Macduff’s baby out of a window 20 floors up. Within the scenes they featured they drifted in and out, sitting on Macbeth’s lap as he caressed them, wiping away blood, stalking corridors like the lost boys.

In a newly created scene devised with Gruff, the audience were invited to join them at a party in the flat that Duncan was murdered in. They danced awkwardly next to his dead body, forcing each other to drink blood and watch the audience squirm as they performed humiliating acts.

Half of the audience saw the witches scene, and half saw the murderers back story, so when thrust together a disconnect was created allowing the audience to share different experiences and understandings of the characters as they reoccurred. Structuring in splits to experiences, much like individual encounters allowed audiences to share experiences. Our overarching objective is to facilitate creativity through inspiring audiences and collaborators to share, react, and build on the narratives we have given them.

Unstructured additions

As the performances wore on over three months of a hot summer, unrehearsed interactions began to grow. The actors playing the witches and many of the stage managers and stewards clambered into audience members beds in the night telling stories in characters, gremlins in our now well-oiled machine.

Our cook, Hilary, began to revel in joining audience as they ate a dinner of Borscht, Peppers and Trifle. She developed a character called Adriana Topolov and began to sell sauces. She would then appear on the roof before the battle scene and launch into an improvised speech usually lambasting the audience for not taking action sooner.

As the rolling news, we had filmed started to show troops descending on the castle we led troops made up of supernumeraries into each flat, breaking down the doors and marching audiences to the roof. In these sequences, just after Lady Macbeth had killed herself, Macbeth had fled in desperation as Burnham Wood came to Dunsnaine. The atmosphere was desperate.

Our recurring character Uri here doubles as news reporter leading the charge and eventually stumbling into people’s rooms, they have gone from observer to observe. Watching the news to being on it. These shifts in perspective as also key to building a universe enabling people to see events from multiple angles and through multiple media.

We also prepared a panel discussion show for the audience to watch, from a safe distance as the audience members felt one kind of reality approaching. These audio visual intervention allows the performance to feel more multifaceted. The filmed footage was never going to be as immediate, but that wasn’t its intention, it was designed to wash over the audience to consider their place in the events.

Over the twelve hours that audience members spent in Balfron Tower our aim was to allow them to occupy and own the world of the story. With the help of a claustrophobic and awe-inspiring space, we built a complex series of scenarios, suggestions, encounters, experiences which channelled the atmosphere of this imposing monolith into the ambitions of its inhabitants. Some of it’s greatest moments were unrepeatable, transient like the soft warmth of a murders blood-soaked palm on your shoulder or a group of strangers bursting into a choreographed dance routine after dinner. As a maker you create the conditions for a journey to be undertaken by an audience member, you are not the party to that journey and it can be an emotional or physical one. This production was strengthened by its strong cohort of collaborators and rich universe but ultimately it allowed the audience to breathe the air of the play, in a similar way that audiences have for four hundred years.

I hope this survey of considerations and practical approaches to making theatre across platforms has been helpful.

These forms have become essential as paradigms for modern makers, there is too little discussion of their impact and definition of these techniques and ideas. Just like when Dziga Vertov tantalising audiences with trains hurtling towards cinema screens, modern theatre-makers now come equipped with the capacity to create intimacy, visceral danger, sow content within performances and bleed cha

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Felix Mortimer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.