Written in 1918, Lu Xun’s A Madman’s Diary marked the advent of modern Chinese literature. Generally understood as an attack on the “cannibalistic” nature of traditional Chinese society and culture, the short story depicts the spiritual awakening of a scholar, dismissed by everyone around him as a bout of madness.

Although it is one of the most influential works of 20th-century literature, A Madman’s Diary does not lend itself to adaptation. More ambiguous than Lu’s later works, even the first paragraph poses challenges to a would-be director: “The moon is bright tonight. I had not seen it for 30 years; the sight of it today was extraordinarily refreshing.” Why 30 years? What happened on this day three decades ago? Why is the narrator suddenly “seeing” the moon again today?

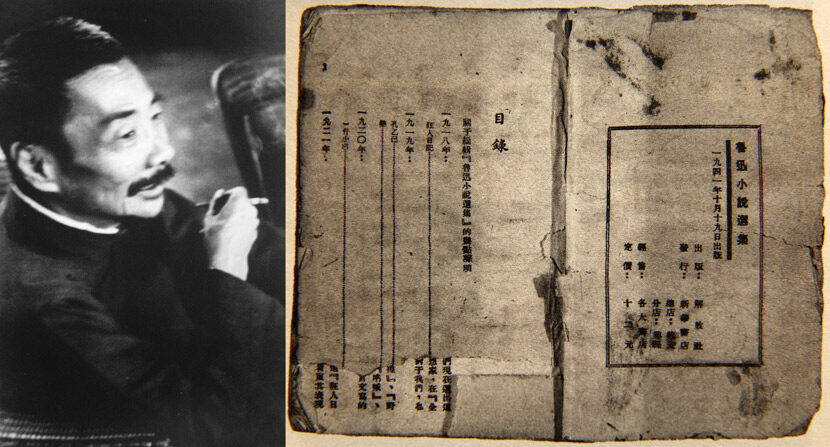

Left: A photo of Lu Xun from 1936. Sha Fei/IC; Right: A collection of Lu Xun stories published in 1941. IC.

The text of A Madman’s Diary is full of such narrative gaps, and the way famed Polish director Krystian Lupa fills them sets his recent adaptation, staged in Shanghai this March, apart from earlier efforts, like Li Jianjun’s from 2011. In fleshing out his script, Lupa draws on Lu’s other tales, from The True Story of Ah-Q and My Old Home to Kite, taking audiences on a journey deep into the minds — or mind — of madman and author alike.

It’s a clever device. Take Lupa’s handling of Mr. Zhou — the name he gives to the play’s narrator and a reference to Lu’s given name, Zhou Shuren. In the first act, Mr. Zhou’s story is so closely intertwined with that of the eponymous madman that the lines between the two begin to break down completely. When Mr. Zhou reaches the lines, “the green-faced gang, they all burst into laughter” in the madman’s diary, the sound of women’s laughter bursts from the next room over. Did this really happen, or was he hallucinating? Where does Mr. Zhou’s world end and the madman’s begin? In Lupa’s hands, the pair are mirror images of each other, effectively circumventing the vertical teacher-student dichotomy that characterizes most stories of enlightenment.

A photo of Krystian Lupa’s stage adaptation of A Madman’s Diary. Shanghai, 2021. Courtesy of Qian Cheng.

In the second act, Lupa abandons the plot direction of the first and pivots to telling the story of the madman. Lupa carefully sorts out the threads of the madman’s character development, laying out the progression of his madness. The opening scene depicts the madman’s epiphany, as we see him running joyfully up to the roof, a clear and glorious space, to feel the new life brought to him by the moon: “Moon, you are here, I am here, I am human, I want to create the world!”

Lupa’s staging accentuates the story’s fantastic elements — one character, a representative of the old order, appears riding on a plume of smoke, self-righteously proclaiming supposedly unimpeachable values: “To disrespect elders and those of higher rank than you is a sin, is evil, and evil is to be eaten by morality.” Lupa here introduces images of the crucifixion, juxtaposing the madman’s suffering with that of Jesus. If this seems like a stretch, it’s not out of line with Lu’s own writings. He wanted to suffer for others as well. In What Is Required to Be a Father Today, Lu declares he will “carry the burden of his own inheritance, shoulder the gates of darkness, and release them, his children, into the wide light.”

If there are two Lu’s in the popular imagination — the man and the myth — then it is the former that Lupa tries to guide us back to. This Lu is not the fatherly figure who stands on high and offers guidance, but a madman, full of sorrow and self-loathing, and always seeking to save himself. “I now realize I have unknowingly spent my life in a country that has been eating human flesh for 4,000 years…I, too, may have unknowingly eaten my sister’s flesh. And now it’s my turn.”

In my opinion, the spiritual high point of the whole play is the appearance of the madman’s mother. This scene gives the most crucial clue as to what’s tormenting the madman’s soul: eating his sister. This is the source of all of the madman’s spiritual woes, and the reason why he grew weak and never saw the moon again.

Yet Lupa also attempts to go beyond the context of Lu’s specific time and place to tackle more universal and contemporary problems. In the third act, a doctor character is introduced to poke fun at modern science, and a university student reflects on the state of contemporary education. Today’s college students were raised on Lu’s work, but in many ways they remain trapped in the same cannibalistic system that the author criticized. There is nothing wrong with these updates: All profound propositions contain a certain universality, and the purpose of contemporary interpretations of classic works should be to explore this universality.

This article was originally published by Sixth Tone on May 3, 2021, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ziwen Gao.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.