Acclimatization refers to the process by which an individual organism adjusts to a change in its environment. The process allows organisms to survive by self-regulating and conforming to a range of environmental and societal conditions. Mountain climbers, for instance, spend a few days acclimatizing themselves to high altitude. What better word, then, to describe the resilience, tenacity, and adjustment of contemporary Iranian women throughout their recent history of revolution, war, economic hardships, and socio-cultural upheavals?

Mahin Sadri, the Iranian female playwright, began writing Hamhavāie (Acclimatization) three years before its successful debut, directed by Ms. Afsāneh Māhiān, in Tehran’s Hafez Hall in 2014. Since then, Acclimatization, a.k.a A Bit More Everyday, has toured other cities in Iran, Turkey, and Europe (Lisbon and Paris). The play garnered the best script award for Sadri and a best acting award for its two actresses at the 2015 edition of Iran’s Fadjr International Theatre Festival. The present analysis is in response to a restaging of the play directed by Kiarash Salimian (Kiārash Salimiān) for the large community of Persians living in Toronto and features the case of Persian audiences in Toronto becoming acclimatized to Iranian women’s climate.

The script of Acclimatization consists of three parallel, interconnected episodic monologues based on a series of interviews and extensive archival research about the true lives of three contemporary Iranian women. As a semi-documentary play, it contributes to the emerging trend of documentary and verbatim theatre that has begun to be well practiced by young Iranian women playwrights in the last decade.

Each monologue dramatizes the life history, memories, and tragic lived experience of three women over the span of three decades since 1980: a war widow (Elhām), a convicted murderer (Setāreh), and a professional mountain climber (Bārān). Their monologues cross, each leading smoothly to the next, often through verbal associations. The characters have no names; the script identifies them by the name of actors but their real identities are recognizable through familiar storylines and associations. The life stories of all three figures have resided in Iranians’ collective memory to various degrees, particularly the compelling case of Shahla Jahed, who was convicted of and executed for stabbing her lover’s wife to death in 2010.

Sara Imānzādeh as Setareh (Shahla Jahed), photo by Sepideh Razi

The opening episode of Acclimatization is about Mahnaz Daliri Fard, the wife of General Abbas Dowran, an acclaimed fighter pilot and a national hero of the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), and the mother of their only child. We listen as Elhām recalls her memories of the first days of her love-bound marriage with Abbas Dowran and the final days of their marriage following his martyrdom in 1982. The narrative then continues to the present, when, after three decades, she still commemorates their eternal love by visiting, washing, and decorating his gravestone, his grave containing only a leg bone. What distinguishes Elhām’s character as an amicable housewife are her virtues of patience, fidelity, and endurance. Her episode, which is narrated episodically in between the other two narratives, creates an extreme emotional experience for its audience, inviting them to witness the physically and mentally agonizing life condition of the bereaved families of martyrs and veterans.

Setāreh’s episodes trace Shahla Jahed’s hidden love affair with Kāzem, the ex-football-player, her emotional ambivalence, the hardship of the life of the sigheh (temporary marriage) wife of a public figure, and the excruciating conditions of convicts in the course of judiciary complications over the span of about fifteen years. Setāreh’s episode draws in its audience with equal emotional engagement, taking them on a journey of connecting, committing love and crime, and an ultimate unjust disconnecting. It is replete with tangible descriptions of Setāreh’s obsessive care and search for Kāzem and Kāzem’s patronizing, often belittling, behavior toward Setāreh. We begin questioning the limits of love, the stakes of and a woman’s vulnerable and marginalized social status and destiny as a secret lover, later a sigheh, and, ultimately, a murderer.

But in addition to showing the precarity of their love life, and the socio-cultural harms of temporary marriage that is much promoted by the Shi’i religious patriarchy, the episode provokes an important question in audiences’ minds about whether the death penalty is and can be a right and appropriate punitive practice.

Azādeh Chāvooshi, photo by Sepideh Razi

Bārān’s episode casts a bird’s-eye view on the daring life struggles of the pioneer of Iran’s women’s mountain-climbing movement. Leila Esfandyāri was the first Iranian woman to, despite all the limitations and discriminations, scale the deadly summit of the Himalayas. On July 22, 2011, having completed the ascent to Gasherbrum II, one of the highest peaks of that range, while returning, Bārān lost control on the ice and fell 300 meters down the mountain. Following her wishes, her body was never recovered and rests in the heights of the Himalayan range. Most of Bārān’s monologue relates her personal and public challenges as a child of divorced parents, as part of a failed remote marriage, and as living an independent resilient life under the coercive systems of patriarchy and norms of the community. Bārān’s life, however, is disturbed by the death of a teammate, whose loss makes Bārān even more determined to fulfill her mountain-climbing goals.

From left Azādeh Chāvooshi, Behnoush Āmery, and Sara Imānzādeh in the final scene. Photo by Sepideh Razi

In the end, the play presents all three women joining in a graveyard as a unified whole, representing the contemporary Iranian woman and the air she breathes in and must acclimatize to, but also signifying a universal picture of the everywoman.

The political power of this semi-documentary play lies in the fact that by relating their thoughts and feelings to each other and to their audience, the characters not only transform private meaning to public meaning but also blur the line between fiction and reality. As a cogent, clever, and timely contribution to the Iranian theatre of the witness, the play attempts to situate its audience as witnesses to the process of witnessing by presenting onstage the testimony of the individuals to whom the events happened, hence arousing audiences’ ethical responsibilities.

Unlike the Tehran performance of the play, the Toronto performance is more humble, simple, and minimal. It was staged in Persian by Kiarash Salimian and his Thousand and One Group at the Small World Music Centre on April 7, 8, and 14, 2018, and toured in Waterloo, Ontario, in May 2018. The group dedicated this performance to all Iranian women. As an active member of the Iranian theatre community in Toronto, Salimian has a history of producing and staging social and political plays, among them The Body Of A Woman As A Battlefield In The Bosnian War, by Matei Vișniec.

The Toronto performance of Acclimatization featured some distinctions from the Tehran production in style, funding, and logistics. In the Toronto revival, simplicity and minimalism are dominant regarding both the mise-en-scènes and blocking as well as the stage props and décor and even the crew. This minimalism is partly due to the lack of financial and professional support, but more importantly, it indicates Salimian’s aesthetic choice. Three big chairs and a broken rope hanging from the top reaching the stage floor, a radio, a bottle of nail polish, a notebook, and a rose are the main props used by the three actresses, who mostly remain seated throughout the show until the last moment. Salimian has a complex lighting design combining frosted whitewash with purple or amber to convey the characters’ mentality and emotions. He uses a sharp red light on the broken rope behind Setāreh at the time of her execution, and in the final moment of reunion when Elhām puts the red rose on the gravestone, the whitewash light that embraces all three women turns into a bright beam spotlighting the red rose.

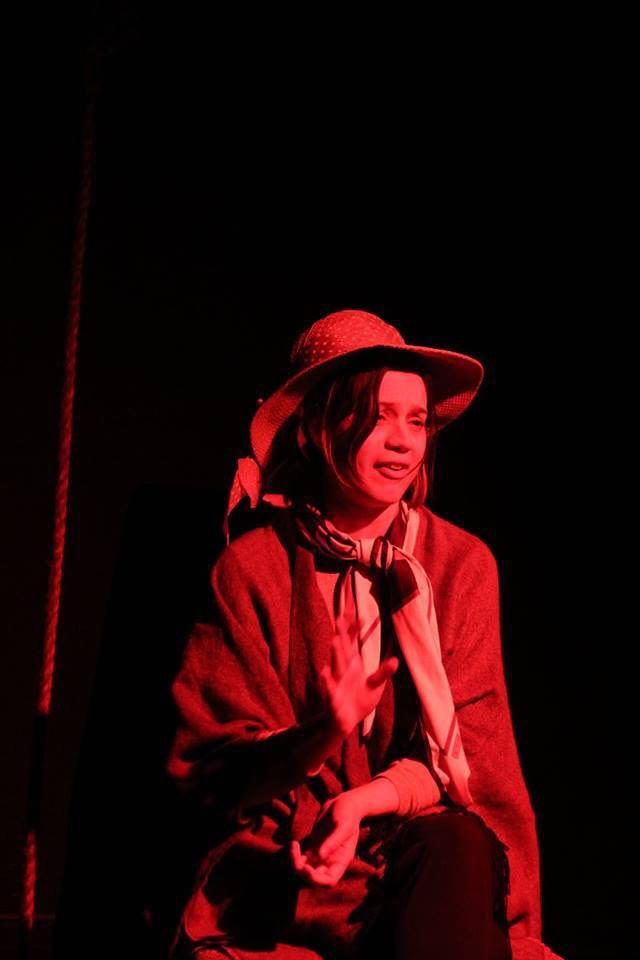

In contrast to the Tehran production, where the actresses had to cover their heads throughout, in the Toronto production, the women observe the dress code only when the textual references require them; for instance, Elhām wears a hijab when she appears in the TV interview or at the graveyard. Likewise, Setāreh’s headcover changes, following the textual clues about the setting of her narrative. As a teenager, her hair has twin tails; she wears a floral scarf when going on her dates; on her foreign trip she wears a floppy hat, and only at the time of her execution does she wear a black chador. Obviously, this freedom in costume and headcover choice demands less imagination and suspension of disbelief and allows the Toronto team to pitch their realistic aesthetics in a different direction.

Sara Imānzādeh as Setāreh (Shahla Jahed), photo by Sepideh Razi and Masih Bohrani

The Iranian diaspora theatre in Toronto has undergone unprecedented growth in recent years. Those immigrants who still pursue their theatrical ambitions in their new home face a variety of issues: harsh material reality, existential fear, a language barrier, the strange and complicated bureaucratic processes of grant application (especially for newcomers), and limited access to professional networks. The director of Acclimatization, Kiarash Salimian, is also the show’s producer and set designer; to mount the show, he depended on personal funding and private sponsors from the Persian community in Toronto. The actresses Azādeh Chāvooshi, Sara Imānzādeh, and Behnoush Āmery are three young and passionate Iranian-Canadian patrons of theatre in Toronto who get involved in their community’s cultural events with little financial expectations. Despite this condition, Iranian diasporic artists cannot ignore their craving for theatre-making, as they find this creative process an opportunity for self-reflection, intellectual liberation, and, often, healing.

Depending on Persian sources of funding has forced many Toronto-based Iranian artists to stage their theatrical productions at the Fairview Public Library Theatre, located in Toronto’s North York neighborhood, where a large population of Iranians live. The fact that Salimian’s group decided to perform at the Small World Music Centre, located in the heart of downtown Toronto, shows their resistance to this cultural ghettoization. Indeed, their choice of venue speaks a lot about Iranian artists’ attempts to de-ghettoize the Iranian diaspora theatre. To Salimian and his team, it was very important to draw their audience to downtown Toronto, which is the hub of Canadian multicultural activities.

The availability of financial support from Persian patrons has encouraged many diasporic theatrical activities to be commercial performances showcasing populistic tastes in putting stories at the mercy of culturally nostalgic signs and themes including Persian music and visual effects. However, Salimian is among those emerging artists in Canada who refrain from being tamed and controlled by the audience’s insatiable appetite for such performances. Having slyly acclimatized their Persian audience in Toronto to non-commercial or nostalgic performances, recently, Iranian theatre practitioners are making timely and important gestures in producing more thought-provoking plays that reflect the shared concerns of current Iranians living in their homeland. The reviews and responses to performances of Acclimatization, both in Tehran and in Toronto, reveal that the creative team were able to acclimatize their audiences to good effect.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marjan Moosavi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.