Marie Curie, whose image as an unsmiling scientist wearing a high-necked, black dress has been immortalized in her numerous portraits, may seem an unlikely heroine for a stage musical, a genre that celebrates excess in every aspect. Yet in the latest South Korean rendition of the figure, she has been successfully transformed into one.

Although the musical features a Polish-born French scientist as its protagonist, it is homegrown in every sense. Its creators are all Korean, whereas many original productions involve an international creative staff these days. The narrative also speaks to the largest musical theater audience demographic in Korea: women in their twenties and thirties who are calling for more diverse representations of women on the stage.

The musical grew out of a series of state-funded ventures over four years with the intention of incubating a cultural export with wide appeal. The libretto, authored by Cheon Se-eun, made its first mark in 2017 as the final contestant of “Glocal Musical Live,” a competition for original musicals hosted by the Korea Creative Content Agency. Subsequently, the musical premiered in 2018 with support from the Arts Council Korea and was showcased at the K-Musical Road Show, a stepping-stone event created to grant international exposure to locally produced original musicals. After extensive revisions, the musical was remounted in February 2020 to popular and critical acclaim and reopened in late summer at the Hongik Art Center.

This is not a typical bio-musical that attempts to faithfully recreate the eponymous scientist’s life in photographic detail. Instead, the musical pulls the accomplished scientist out of her safe, insulated, brick-walled laboratory to face the consequences of her discoveries in the outside world. In a bold, imaginative leap, Cheon, the librettist, places Marie’s discoveries side by side with a historical event that occurred in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century: the death of the Radium Girls, who suffered terribly from radium poisoning after years of painting luminescent watch faces using radium paint. The dying women’s collective fight against their former employers became a landmark event in American labor history, holding companies accountable for occupational illnesses and ushering in labor reform.

By condensing these transatlantic events—from Marie’s discovery of radium to the tragic deaths caused by the industrial uses of radium—into a 150-minute show, the musical not only illustrates Marie’s struggle as a woman and an immigrant but also highlights the challenges she faced as a scientist. For this reason, the musical feels like a chemical experiment in itself: what happens when Marie’s determination and passion for new scientific discoveries run into questions of justice and ethics? Marie’s confrontation with the destructive consequences of her discoveries adds volumes of drama and successfully transforms the titular character into a musical diva.

The musical opens to reveal Marie the night before her death, writing her own obituary in plain, clinical language as though she were taking notes in her science journal. Irène, her daughter, cannot understand why such an accomplished scientist as Marie—a two-time Nobel Prize winner who discovered two elements—would want to make such an un-celebratory exit. With a bitter smile, the trailblazing scientist decides to reveal a problem she was unable to solve: an unfulfilled promise to a friend who has been alienated from her for many years.

As Marie’s story unfolds, the stage transports the audience to a bustling train station where Marie Składowski, now a young woman, is about to board a Paris-bound train for her studies. The journey starts with Marie singing her delightfully vibrant number “Map of Everything” in a narrow spotlight. As she professes her dream to find a place and name for every element that exists, sketches of the incomplete periodic table and chemical equations are projected on the stage as though waiting to be filled in by the budding scientist.

On the train, Marie runs into a fellow Pole, Anne Kowalski. She is a fictional character who serves as Marie’s connection to the homeland and as a voice for morality and justice in the musical. Anne comes from the peasant class, but instead of marrying another farmer and following standard societal mores of rural Poland, she chooses to try her luck in the modern urban center of Paris as a factory worker. Sharing Polish roots and ambitions to defy their gender-prescribed roles, the independent young women bond instantly and set out on a journey to find a name and place for themselves.

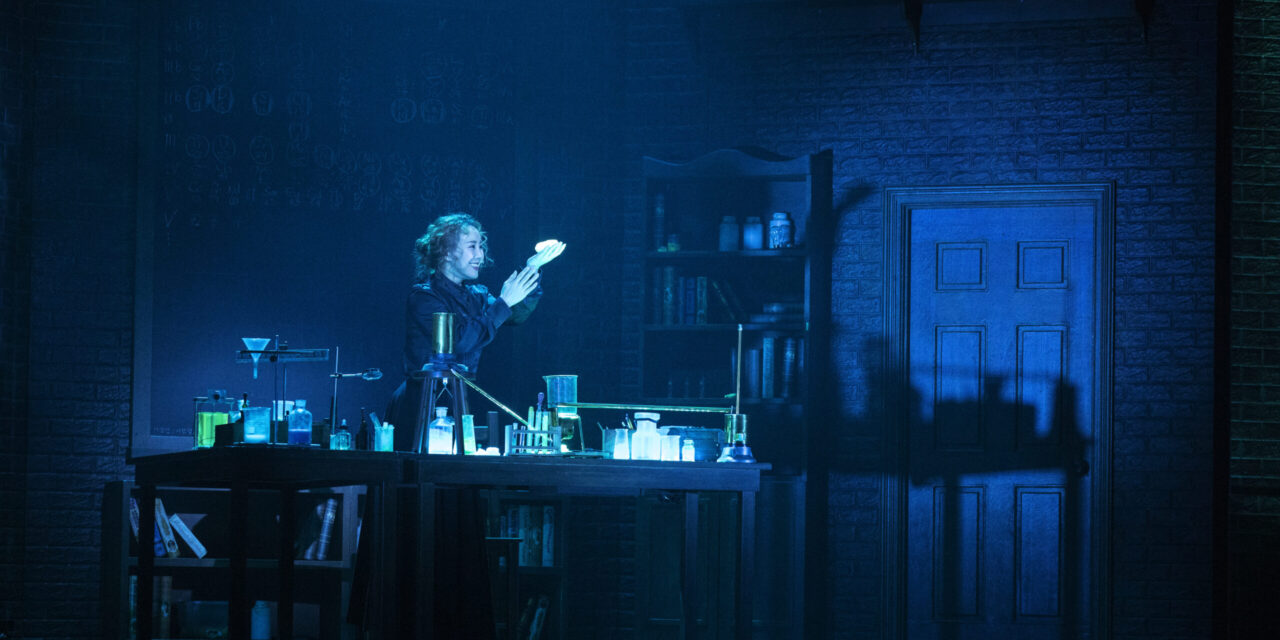

Musical Marie Curie (2020) at Hongik Art Center. Photo Courtesy of Live Corp.

Through a series of fast-paced vignettes, the musical’s first act is mostly devoted to dramatizing the women’s individual struggles and growth in their adopted country. As a woman and an immigrant, Marie strives to establish herself in the male-dominated French academia, which is unwelcoming if not outright hostile to the Polish woman. Meanwhile, Anne quits after finding the working environment at her first job exploitative. Marie soon finds an anchor in her intellectual and romantic partner, Pierre, and gains recognition from the scientific community through her discovery of two elements: polonium, named in honor of her native country, and radium, named to reflect its radiant qualities. This remarkable achievement turns the situation around for Anne as well. She lands a new job at a radium dial factory, Undark, which is cashing in on Marie’s latest discovery as well as Polish immigrant labor. Both women seem to have reached their dreams and are elated by their new lives.

Musical Marie Curie (2020) at Hongik Art Center. Photo Courtesy of Live Corp.

The second act takes on a somber tone when Marie realizes radium can be as destructive as it is curative, and that the lives of her loved ones may be at risk. This recognition, which she was rather reluctant to acknowledge in real life, marks a transformative turn for Marie, who now has to face the real-life consequences of her research. Anne’s call for justice for the dying workers inspires the scientist to engage in her own battle to ensure radium’s ethical and safe use against those who try to obscure the truth. But the musical does not transform the scientist into an activist. Marie does what she does best and carries on with her research, this time to illuminate radium’s harmful effects.

A notable number in the production is “Radium Paradise,” a showstopper performed in top hats and white- and green-sequined costumes. The instant the Curies announce that they would not patent their discovery, entrepreneurs flock to the stage to capitalize on the wonder element and promote it as a cure-all. The razzle-dazzle staging communicates the lucrativeness of the radium industry as well as the utopic appeal of the new element. (Radium’s popular appeal and level of infiltration into public consciousness can be felt in the 1904 Broadway musical Piff! Paff! Pouf!, which featured a glow-in-the-dark spectacle titled “Radium Dance.”) Yet the staging also foreshadows with irony that the hype is a show put on by entrepreneurs who later play a significant part in downplaying radium’s danger to deny worker protection. The coupling of a cheery, toe-tapping tune with the list of cosmetic and medical products ranging from radium toothpaste to radium condoms is staggering. One shudders at the thought of being exposed to the element unknowingly as a worker or consumer.

The Curies’ duet “Unpredictable and Unknown” is another memorable number. In this sweet and elegant ode to scientific research composed by Choi Jong-yun, the couple sing of their burning passion for exploring the unpredictable and unknown. The performance not only conveys their shared love for science but also their affection for each other. Kim So-hyang, who originated Marie’s role, sparkles with curiosity even in a black dress, and Lim Byul, in his supporting role as Pierre Curie, balances Marie’s excitable character with calm affection and tenderness. Although the musical provides sparse details about the couple’s relationship, the number captures the essence of their love magnificently.

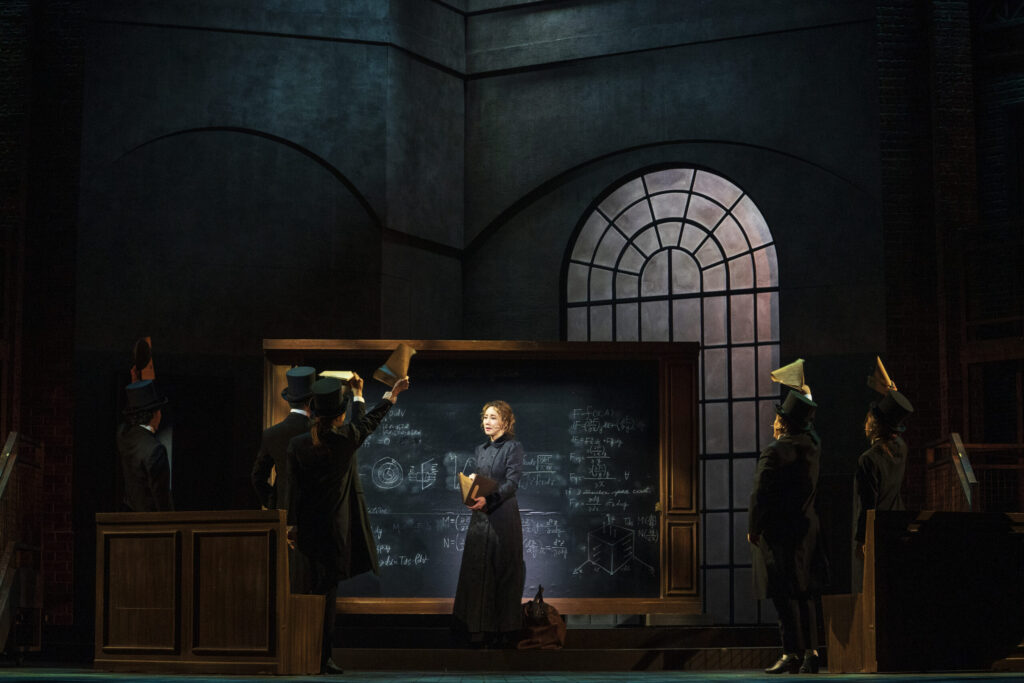

Kim Mi-kyung’s set is neat and pragmatic. The revolving stage alternates between Marie’s laboratory and the Sorbonne classroom, where the brick walls, tall arched windows, and wooden set pieces evoke the architecture of the time. Hong Moon-ki employs a mostly toned-down palette for the costumes, yet Marie’s famously plain floor-length dress and the modest, neutral workwear of the factory workers serve the characters well and make them feel authentic. The production is handsomely illuminated with Lee Ju-won’s lighting and projection, which recreates the mesmerizing and enchanting effect of radium that captured the heart of the Curies’ and the public more than a century ago.

Under the deft direction of Kim Tae-hyung, who has a background in the natural sciences, the musical unpacks the Curies’ experiments and research in a surprisingly entertaining and humanizing way. Yet the musical at times feels a little overloaded because it tries to merge two different historical events to create dramatic moments. One character who needs more justification and development is Ruben Dupont, the chair of the radium dial factory. He is portrayed as a generous supporter of science and a benevolent entrepreneur for the first half of the show. Later, however, he suddenly transforms into a villain who denies workers’ rights and actively suppresses the truth about radium’s destructive power. His connection with other institutions is hinted at only in passing, and his motivation remains veiled. Such characterization borders on melodrama, obscuring the complex psychology and institutional forces that may have been at work.

Musical Marie Curie (2020) at Hongik Art Center. Photo Courtesy of Live Corp.

The musical comes to a close when Anne’s letters and scrapbook arrive in the mail just before Marie breathes her last breath. In these documents, Anne bears witness to Marie’s efforts and legacy to keep radium’s damaging effects contained and limit it to curative and ethical use. A periodic table may sound like the last object to move your heart, but the most touching moment of the musical is when we see the periodic table again from the first act. What had been left incomplete in the opening scene is now complete: Anne stands inside the box marked polonium, and Marie, radium. Through their friendship, reaching beyond their socioeconomic differences, the women have found their place in the world and a name for themselves.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Hansol Oh.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.