Ah, if only we could take a trip back in time, to an era when the surfacing of facts that pointed to misuse of authority by those in power could actually topple the mighty, and when we could imagine that judges were more interested in justice and honor than in propping up a corrupt but pragmatically useful status quo.

That’s the time Aaron Sorkin’s 1989 play A Few Good Men transports us back to for a couple of blissfully wishful hours. I don’t know whether the play’s revival at the Pittsburgh Public Theatre is meant to leave us hopeful (that such times might come again) or despairing (that we have lost our innocence forever). Certainly, it shoots a very of-the-moment question across the bow: how has it come to pass that this depiction of truth defeating venality could feel like such a quaint fantasy?

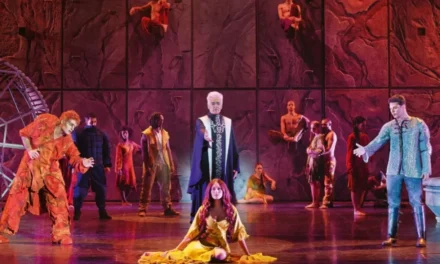

Burke Moses as Jessup. Photo by Michael Henninger, courtesy Pittsburgh Public Theater.

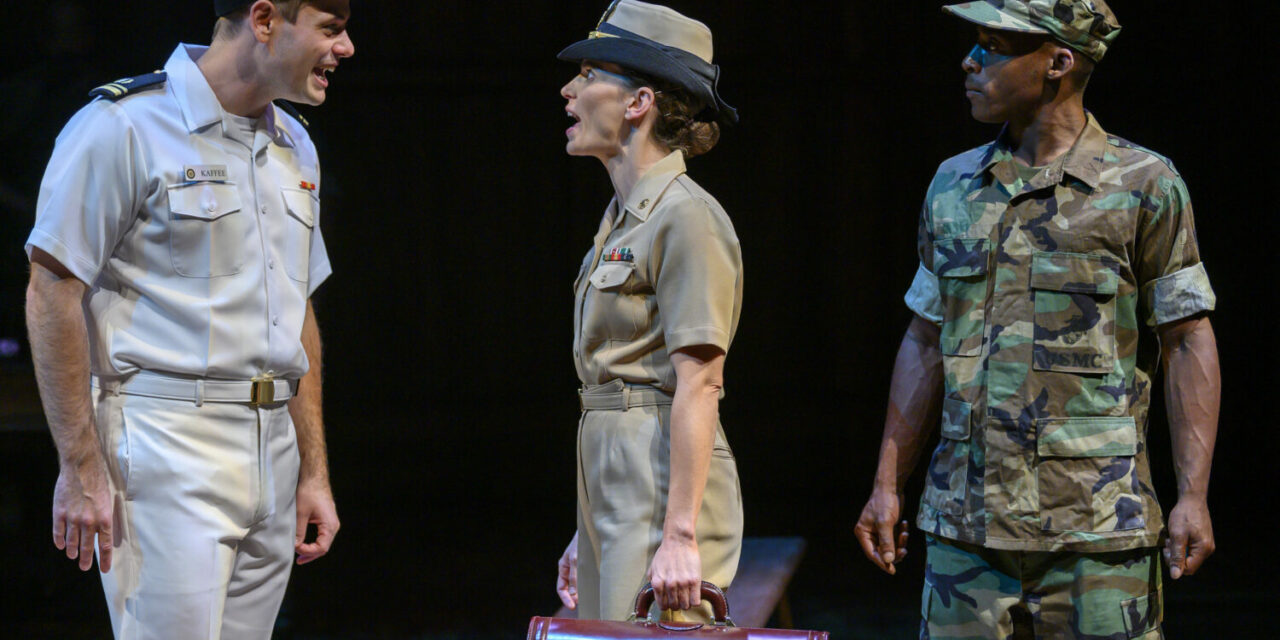

You may be familiar with the film version of Sorkin’s courtroom drama. If you aren’t – and I myself wasn’t – the conventionality of the plot is such that a quick summary will hardly spoil it; indeed, part of the deliciousness of watching this play lies in knowing that the narcissistic and callously self-righteous base commander Lt. Col. Jessup (Burke Moses, gloriously detestable in the role) will get his comeuppance in the end at the hands of the rookie navy lawyers Galloway (Alison Weisgall), Kaffee (Doug Harris), and Weinberg (J. Alex Noble). The story revolves around the case of two marines, Dawson (Ryan Patrick Kearney) and Downey (Michael Patrick Trimm), who have been accused of murdering a member of their squadron. Galloway suspects – correctly, it turns out – that the two men had been ordered by a superior officer to carry out a “code red” (a form of hazing used to informally discipline marines who are failing to toe the line), and she manages to have their case moved from Guantanamo Bay, where they are stationed, to Washington D.C. so that they can have a proper trial. She also wants to defend them, but the assignment is given instead to Kaffee, a charming bad-boy Harvard law grad more interested in excelling at softball than defending clients. His forté is the well-negotiated plea bargain, but Dawson and Downey insist on mounting a defense of their innocence in the court-martial, forcing the inexperienced trio to go up against the much savvier and politically deft prosecutor Jack Ross (Kyle Haden).

Sorkin crafts his plot to build maximum tension over whether or not our three legal Davids will slay their Goliath: the depiction of the trial is interrupted by flashbacks to the events surrounding the killing as well as by scenes showing the defense team attempting (mostly unsuccessfully) to collect evidence of the commanding officer’s coverup of his complicity, so that we, as audience, become increasingly invested in the desire to see him brought to justice. Under the agile direction of Marya Sea Kaminski, the enormous ensemble makes that tension electric: as sure as I was that the underdogs would win in the end, I still felt mounting anxiety, as the trial progressed, that our legal heroes might not be clever or crafty enough to nail the villain.

I was also acutely aware – in ways that perhaps the original audience might not have been – of the gender politics of Sorkin’s setup. Nineteen characters appear on stage in this production; only one of those, Galloway, is female, and I imagine that the scene in which Jessup attempts to put her in her place through crude sexual “humor” must have played very differently in 1989 than it does today. Yet another fantasy this production allows us to indulge is that a woman might be able to keep her composure and muster a dignified retort after being subjected to such a Trumpian mode of humiliating sexual harassment: Weisgall’s resolute and unflappable Galloway made me believe it actually could be done.

Strong performances all around make the storytelling rich and juicy. Rounding out the main roles in the play are Jason McCune and Ken Bolden as Kendrick and Stone, the enablers to Jessup’s authoritarian corruption, and Cotter Smith as Markinson, one of the “few good men” in the scenario, who makes the ultimate sacrifice to achieve justice. The role of the court-martial judge rotates between Rocky Bleier, Larry Richert, and Monteze Freeland. Kaminski has also enlisted several serving members of the armed forces into the ensemble, and she uses muster drills and chants effectively to punctuate the scenes and lend authenticity to the production’s portrayal of military etiquette and discipline. The combination of Ryan Howell’s open, flexible scenic design and Joe Spinogatti’s scene title projections allow Kaminski to stage nimble transitions between scenes and keep the action moving at a gripping pace.

Like a Proustian madeleine, Sorkin’s snappy banter may conjure nostalgia for the idealism of his popular TV show The West Wing; that is, for a time when the terms “government” and “service” went together naturally. In retrospect, this play – like so many cultural artifacts from the eighties and nineties – feels prescient, particularly in the way it taps into the strategies alpha males use to maintain their grip on power. In today’s context Jessup’s smug misogyny, in combination with his contempt for people like the Ivy-educated Kaffee and the Jew Weinberg, puts him into a very familiar category, and when the elites he despises manage to hoist him on his own petard it feels more than a little like a dream come true.

This article was originally posted in The Pittsburgh Tatler on 23 September 2019 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Wendy Arons.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.