The British directing star Robert Icke specializes in contemporary adaptations of classics. He writes and directs them, proudly insisting that they only deserve attention if they hold their own as current plays. No foreknowledge of the originals should be needed. “When you deliver a classic,” he says, “your primary responsibility is to try and catch some of the lightning in the bottle that made it happen when it first appeared. If you don’t do this . . . you might just do a new play.”

This is a worthy ambition, and a bold claim. And now, finally, with Oedipus he has met it. The examples he brought to New York before didn’t convince me.

1984, produced on Broadway in 2017, was a murky and overmediated disappointment. A solo version of Enemy of the People and The Doctor (Ibsen and Schnitzler adaptations) at the Park Avenue Armory were happily more effective—both sharp and vivid with intense present-day immediacy. Then The Oresteia (also at the Armory) was another misfire. The modernization was patently absurd, asking us to believe that a popular, contemporary politician in a democratic country would actually ask a toady doctor to give his healthy and beloved daughter a lethal drug cocktail. Please!

I’m relieved to report that Oedipus is good. In fact, it’s a rare achievement. Originally produced in Amsterdam in 2018 and just opened on Broadway, it’s gripping, smart, searingly acted, and very cleverly adapted to its modern circumstances. As with The Oresteia, a Greek classic has been adjusted to fit a present-day politician running for national office in an unnamed country, but this time it doesn’t have such ruinous plausibility problems. The story is importantly and perceptively rebalanced to give Jocasta a full and pivotal backstory, and Lesley Manville’s performance of that role is unforgettable. As is Mark Strong’s as Oedipus. Both rise to an epic occasion.

Sophocles’s Oedipus the King, written 2500 years ago, is one of the most famous and influential plays in the Western canon, and there are plenty of very free adaptations of it. Interestingly enough, Icke has hewn closely to its basic plot while shifting its underlying point. Sophocles saw the tale of a man who inadvertently kills his father and marries his mother as a parable about the limits of human knowledge and the unknowability of fate—everything preordained. Icke uses the story as a case study on the contingent nature of truth. It doesn’t really matter in his version if the situation was preordained. No one cares. The question is whether it truly had to be uncovered.

Icke’s Oedipus and Jocasta deeply love one another. That is front and center. She has secrets she never shared, but they’re understandable: she was raped by Laius, leader of the unnamed country, at age 13 and the resulting baby was pried from her arms at birth (presumably to die) as evidence of the great man’s predation. Now, for 24 years, she’s been married to a man she adores and admires, and has 3 grown children. Maybe the hurtful past could . . . you know, stay in the past? Fat chance. Not in the media age, in the glare of public life.

The play opens with a large-screen video clip where Strong-as-Oedipus, running for high office, is interviewed in front of an adoring crowd. He’s an appealing populist calling for a new era of honesty and boasts of being a political outsider (notwithstanding that he’s married to Laius’s widow). On camera, he impulsively goes out on 2 limbs: vowing to open a new, fully transparent investigation into how Laius died and promising to release his birth certificate to squelch nasty rumors about his foreign origins. If you know the original, this is terrific. The political enormity of the gaffe is immediately as vivid as the personal stakes.

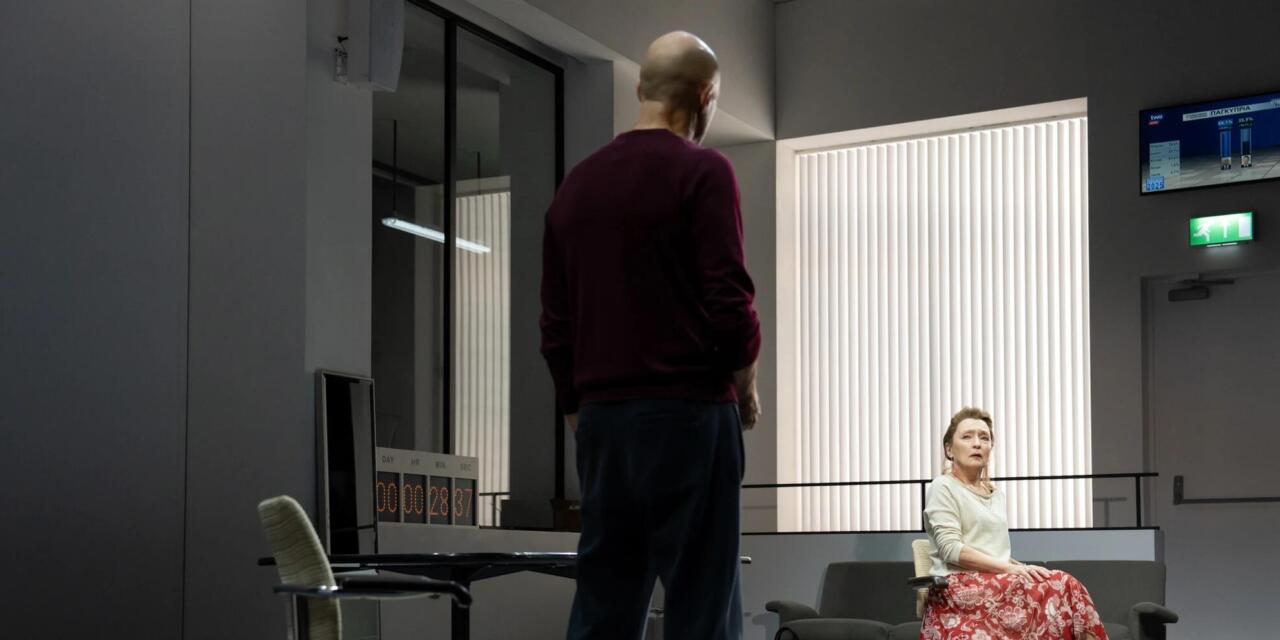

I particularly enjoyed how Icke blended the domestic and the public in this piece. He sets the action in Oedipus’s campaign headquarters—a spare, white, modern space with a digital clock counting down the minutes until the votes are in—which serves all the expected official purposes of strategy sessions and the like but also easily shifts (with swivel doors) to accommodate private encounters like a family dinner, personal squabbles, and sex acts. The domestic scenes are peppered with grim little jokes based on what the speakers don’t know, such as Jocasta’s, “I actually tell people, I have four children, two at 20 one at 23 and one at 52.”

L to R: James Wilbraham (Polyneices), Olivia Reis (Antigone), Mark Strong (Oedipus), Lesley Manville (Jocasta), Jordan Scowen (Eteocles), Anne Reid (Merope), Bhasker Patel (Corin). Photo: Julieta Cervantes.

We meet the three kids and learn, for instance, that Antigone is a bossy and provocative academic, Eteocles gay (inconsiderately outed by his brother Polyneices), and Oedipus remarkably liberal about sex (“why are we embarrassed about love?”). That last point thoroughly irritates his adoptive mother Merope who—oops!—never told him he was adopted and rushed over to set him straight after seeing that alarming birth certificate remark on TV. In a comedy-of-delay gag that lasts the whole tragedy, Merope is never given a moment alone with him until the catastrophe is nigh.

There is plenty to quibble with if you care to. Icke makes the prophet Teiresias a buff, young, tattooed member of a strange “future-teller” cult who just shows up and warns Oedipus for no evident reason; in Sophocles he’s an old man who speaks only on threat of torture. And Antigone’s provocations feel equally unmotivated, such as when she accuses her dad of infidelity out of the blue, at the dinner table, without evidence. For me, though, such glitches fade to unimportance beside what is powerfully right.

Sophocles’s play itself, it’s worth remembering, contains one very big plausibility problem from a modern viewpoint: that the man never bothered to ask his wife (recently widowed when they met) how her first husband died. Icke has resolved this issue so thoroughly and movingly that the secret and its disclosure become the production’s greatest assets. Jocasta’s reluctantly told backstory is Icke’s best writing, and it’s so harrowing, ugly, horrifically entrapping, and damaging that we end up with no questions about why she kept it to herself for so long. She may harbor multiple protective repressions, but she is no fool and no self-deceiver. Through her, Icke’s Oedipus becomes a tragic #Me Too story in which the truth comes out at deadly cost to the innocent and guilty alike.

Oedipus is usually the star of his play—and Strong indeed performs him as a brilliantly stubborn, self-regarding, wannabe savior who has started believing his own P.R. Icke is even more interested in Jocasta, though, as he turns our attention toward what she knew and when she knew it, the better to ponder questions about what disclosures are really morally necessary. Maybe the incest taboo needn’t be so absolute?

For this reason, his play feels closer in spirit to modern works about beneficent life-lies like Ibsen’s The Wild Duck and Pirandello’s Right You Are (if you think so) than it does to Sophocles. Icke’s Jocasta makes you wonder whether the story’s tragic end had to be inevitable.

Created by Robert Icke after Sophocles

Studio 54

This article appeared in TheaterMatters on November 17, 2025, and has been reposted with permission. To see the original article click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.