We Live in Cairo, a new musical written by brothers Daniel Lazour & Patrick Lazour, directed by Taibi Magar and presented at the American Repertory Theater, begins with the actors on stage teaching the audience the chorus to a protest song. The actors are not yet in character but we’ll soon learn that they will be portraying activists involved with the Egyptian 2011 uprising, a key event during “The Arab Spring.” These activists consist of a pair of street artists, a photographer, a brother duo of singer-songwriters, and a hardened protester recently free after a stint in jail. The actors sing beautifully a capella but struggle to fully teach the audience both the lyrics and the melody in the time allotted. The actors return to the song a few more times during this two-hour long musical and each time the audience’s singing shifts gradually into quiet mumbles, partially due to forgotten lyrics, partially due to lack of clarity if we the audience should be actually joining in each time. By the song’s final appearance, it’s unclear why the show opened with us learning the song in the first place.

This throughline is indicative of what We Live in Cairo is as a whole: a group of energized artists committed with full hearts to telling an important and true contemporary story but with hit or miss ideas, both in the book and in the direction, that are often unable to connect with each other to form a profound whole. Lazour & Lazour wrote their musical after being inspired by a photograph of young Cairenes organizing protests over a MacBook (see photo below) and spent years researching the history and circumstances of the protests to successfully create a musical that shares the complex and true story of the 2011 Egyptian uprising. However, We Live in Cairo struggles as art due to an overemphasis on a docudrama plot over character and story development, a maladroit use of the musical medium, and the aforementioned incoherent blend decisions in spite of the boldness of ideas.

Following years of government corruption and cover-ups, the brutal murder of 28-year-old Khaled Said at the hands of Alexandrian police was a final spark that ignited the 2011 protests in Tahrir Square, Cairo. Largely organized online, demonstrations swept the country, resulting in Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, stepping down after 30 years of rule. The story of youth weaponizing social media to bring down a dictator is inspiring, but sadly without a happy ending. In 2012, the far-right Muslim Brotherhood, led by Mohamed Morsi, filled the void Mubarak left behind and in 2013, a military coup removed Morsi, leading to protests and many deaths–the government claims 600 casualties; human rights groups estimate closer to 2,600. In the present day, Egypt appears effectively no better off than during Mubarak’s reign.

The characters in We Live in Cairo share this fascinating true story, but add little else to the plot; the storyline of the musical boils down to the characters primarily discussing the above events. In an attempt to craft a dramatic world, Lazour & Lazour rely on theatre cliches. A beloved character dies only to return a la Angel/Fantine for a final musical number. Not one, but two forbidden Romeo-and-Juliet type love stories are featured in the show: one between a Christian man and a Muslim woman, another between two gay men. But these characters’ personal stories are secondary to the story of national events and it’s difficult to emphasize with the characters themselves when they are often passively narrating the news instead of actively pursuing their own defined goals.

There is a moment in the middle of the first act in which street artist, Karim, played by the wonderfully charismatic Sharif Afifi, is confronted by police for his facial piercings. Karim escapes arrest thanks to his scapegoating homophobic pandering and name dropping his military father. It’s a gripping scene that lets Afifi embody a fascinating and contradictory character, but it is only one of a few truly character-driven scenes in We Live in Cairo.

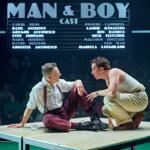

All of the actors sing the Lazour brothers’ diverse and rich score with zest, but the best musical moments on stage were those involving Jakeim Hart who plays the protest musician Amir, rarely (if ever) without guitar in tow. Hart is a consummate musician with a stunningly easy and smooth voice. His tight harmonic duet with Parisa Shamir, who plays the photographer Layla, was simple, lovely, and sweet. However, musical moments not centered around Hart as Amir lacked comparable power and if anything, felt out of place. We Live in Cairo is not sung through, but oddly, some scenes were. During a scenic climax in the second act, Dana Saleh Omar, as the veteran protestor Fadwa, shifts into to a lengthy sung/spoken monologue while her scene partners observe silently and the energy of the scene dissipates. Scenes like this demonstrate that while Lazour & Lazour are adept songwriters, they aren’t yet able to use their music to advance or enrich their story.

Jakeim Hart and Parisa Shahmir in We Live in Cairo. Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

We Live in Cairo is filled with these kinds of bold ideas that, while exciting, occasionally miss the mark. White curtains are hoisted like sails throughout the Loeb Space onto which projections plaster social media feeds and videos. The effect is visually impressive, but the loud cranks of curtain ropes distract from the singing on stage and often the effect is used only for further exposition. Actors burst into the audience with chants of “Down with the President!” which makes me consider calls for impeachment for our own president and leads me to actually emphasize with Trump (which I certainly hope was not the intent of the production team) when directly comparing him with the objectively worse Mubarak.

Tilly Grimes’ costumes are dynamic. As Gil Perez-Abraham’s Hassan grows from naive artist to Westernized activist, his clothing changes reflect his transformation. Kai Harada’s sound design successfully connects with the rest of the technical elements; David Bengali’s projections shuddering as Harada’s bass drops is a particularly satisfying detail.

The cast of We Live in Cairo. Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

If you are interested in the contemporary Middle East, make a trip to the A.R.T. to see this new musical and learn more about this fascinating story largely unknown to the Western public. And although the show at times is messy or flat, We Live in Cairo teases enough exciting moments that will make you want to keep an eye on the future work of Lazour & Lazour.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rem Myers.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.