The ghost of Pina Bausch was no doubt fluttering with excitement around the NAC last month as the contemporary formation of her company brought us all back to the very origins of the idea of Tanzthe a ter, dance that incorporates words, foregrounds a heightened form of theatricality, and much much more. All that came through very strongly last night in the Opera of the NAC before a packed house, waiting religiously to see the company from Wuppertal perform works that most people have not seen before in Ottawa.

In 1984 when the company first came to this city with Kontakthof, there was angry booing, as one man shook his cane at the stage and stomped out of the opera slamming the door behind him. Women manhandled by the males, strutting about the stage trying to zip up their dresses and carrying out apparently awkward everyday gestures had never been presented as dance before. Thanks to the foresight of Yvon St-Onge, the producer of dance at that period, we were introduced to the most innovative dance in the world and the Ottawa audience became a highly sophisticated observer of corporeal performance, prepared for the coming of all the best in the world and the coming of dance director Kathy Levy who continues that tradition.

The program, now being presented at the NAC in Ottawa brings us back to the very source of the Wuppertal Tanztheatre aesthetic and helps us forget the disappointing concessions that have been made to contemporary audiences in several of the more recent pieces by the company since Pina Bausch’s death.

Café Müller, created in 1978, reveals the visions that underlie the intense theatricality of this “dance-theatre” company. Inspired by a heightened realism that shows its expressionist origins, it combines a deeply symbolic gaze that eradicates all narrative and transforms the human body into signs of contemporary engagement with the world. Locked in an enclosed space that could be a Restaurant or even a German Kneipe filled with chairs and tables, a woman in a semi-trance moves gracefully but with difficulty through the revolving doors, as light floods slowly into the area. Even the lighting establishes a certain visual authenticity in this space surrounded by fragments of transparent walls.

Are they closed inside a cage as prisoners of the German wall that split the country, are they driven into submission by the male presence that appears to control their movements? Is that masculine figure in the gray suit preventing the woman from moving freely or are the males in suits offering some sort of protection by kicking the chairs and table violently out of their way? This explosion of power and submission evolves quickly. Pushed into the arms of a weaker young man in a shirt, one of the women in a gesture of abjection keeps clinging to that weaker male as both are forced into the empty loving gestures by the man in the dark suit, watching them. These loving gestures are reiterated and evolve rapidly into clinging and dropping as the woman rolls to the floor in an uncontrollable expression of helplessness. Although both the woman and the man are caught up in gestures of violence as they push each other against the transparent walls, the young woman is the ultimate object of this violence as she drops to the floor and is scooped up by her partner, an image of male cruelty that defines the female.

At the same time, various other mini-events appear and disappear in that space, one of the most ambiguous figures appears to be a tall, slim, near-transparent female figure out of a symbolist painting, gracefully floating around the edge, watching but keeping on the sidelines. She infuses the tableau with a deathly spirit of absence, leaving a powerful impression on the tableau that thrusts us into the 21st century.

Suddenly we are able to shift to 2017, where a new world of migrants invading a traditional German space, is subjected to mistreatment and exclusion. It is all there! In this world of potential and real violence, the soaring music of Henry Purcell fills the air with the richly lyrical tones of a sacrificial ritual, carried by the disturbing magnificence of a beautiful soprano voice. This dizzying spiral of meaning creates a clear link between the world of Café Muller and the choreography of The Rite Of Spring.

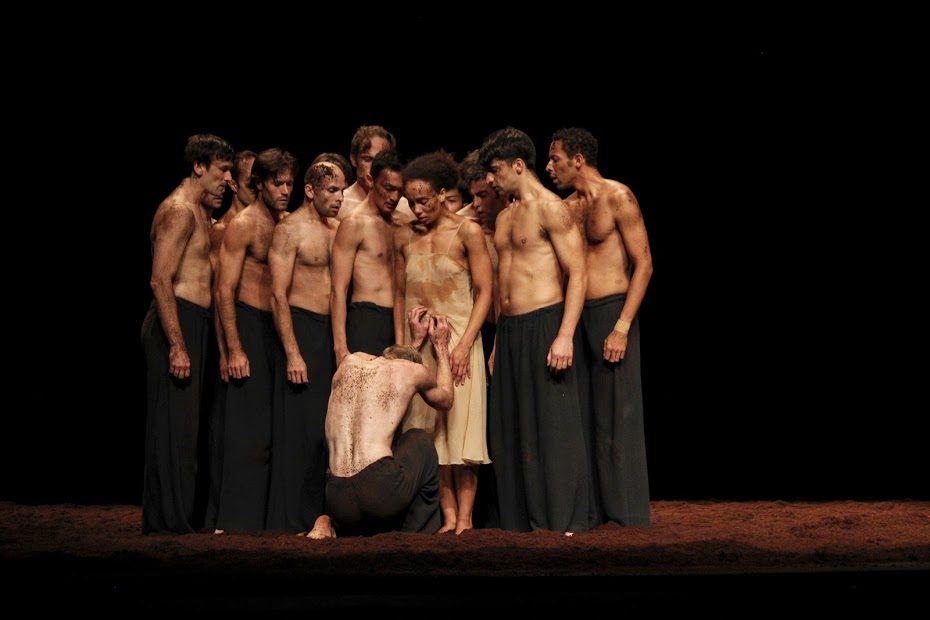

Clearly betraying moments of collective choreography that moves from the Diaghilev world of Russian peasants transformed by the gazes of Nijinsky and his sister, through German expressionism and Maurice Béjart’s orgiastic vision of the stage, Pina Bausch has interpreted Stravinsky in her own wildly visceral and exciting way.

In this primitive world of instinct, the powerful males and delicate females face off, vibrating in contact with each other, excited by the odors and feelings of damp earth under their feet and smeared over their bodies as they anticipate the violent copulation, the ultimate immolation that signifies the return of new life. Are we touching on a new vision of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty which the writer described but never realized in his lifetime? That is certainly possible. The rising excitement sweeps us away with the urges of mating and subsequent dying as the chosen victim is possessed by a frenzy of self-destruction. This is well articulated in Stravinsky’s music, heightened by the strong movements of the dancers and the NAC Orchestra under the direction of Joana Carneiro.

This was certainly one of the unforgettable moments in the history of Dance programming at the NAC. Café Müller and The Rite Of Spring played at Southam Hall, NAC from September 28 to 30, 2017.

This article was originally published on Capital Critics Circle. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alvina Ruprecht.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.