In an 1896 essay on “The Tragic in Daily Life,” the Symbolist playwright Maurice Maeterlinck extols the virtues of the silence and stillness that typify his own static dramas, maintaining that ostentatious theatrical display only distracts from the subtle vibrations of authentic being. “I have grown to believe,” he writes, “that an old man, seated in his armchair, waiting patiently, with his lamp beside him, giving unconscious ear to all the eternal laws that reign about his house, interpreting without comprehending… submitting with bent head to the presence of his soul and his destiny—an old man…motionless as he is, does yet live in reality a deeper, more human, and more universal life than the lover who strangles his mistress, the captain who conquers in battle or the husband who avenges his honor.” Trade the old man for four women in their seventies, and this is a fine précis of the phenomenology of Caryl Churchill’s captivating Escaped Alone.

This sharp sigh of a play lasts less than an hour, but in it Churchill conjures an impressive panorama of time-bound and timeless anxiety, from relatively minor quotidian struggles to apocalyptic visions. The play begins with a Mrs. Jarrett coming upon a little garden in which three women she knows sit jawing away a sunny afternoon, apparently quite content. She joins them. The conversation ranges over familiar topics—family, popular television shows, the benefits of retirement, and the physical infirmities of age. But this surface banter is periodically pierced to give us a closer look at consciousness. Penetrating the psyche of each woman in turn, Churchill reveals their incommunicable afflictions. For Sally it is crippling ailurophobia, the persistent, irrational fear of cats. For Lena, depression that makes it difficult to see the point of hauling herself out of bed to “do talking” each day. Vi stabbed her husband to death in their kitchen long ago (though no one can remember for sure whether or not the ghastly incident was an accident), which has made it difficult for her to feel entirely comfortable in any kitchen since.

Their private plights are not shameful secrets; each spiritual ailment is casually, often humorously discussed by the group, but then the lights will shift, isolating one speaker who then addresses the audience as she offers her unvarnished truth. Mrs. Jarrett is given more opportunities to engage with us directly, but her personal divulgences take a different form. She describes surreal, elaborate global disaster scenarios that, while outlandish, contain stray, uncannily familiar details. “The hunger began,” she explains in one of seven speeches, “when eighty per cent of food was diverted to tv programmes. Commuters watched breakfast on their way to work. Smartphones were distributed by charities when rice ran out, so the dying could watch cooking…The obese sold slices of themselves until hunger drove them to eat their own rashers.” It sounds like a nightmare, but then Silicon Valley really has spawned initiatives in recent years to help alleviate want by distributing smartphones to homeless people.

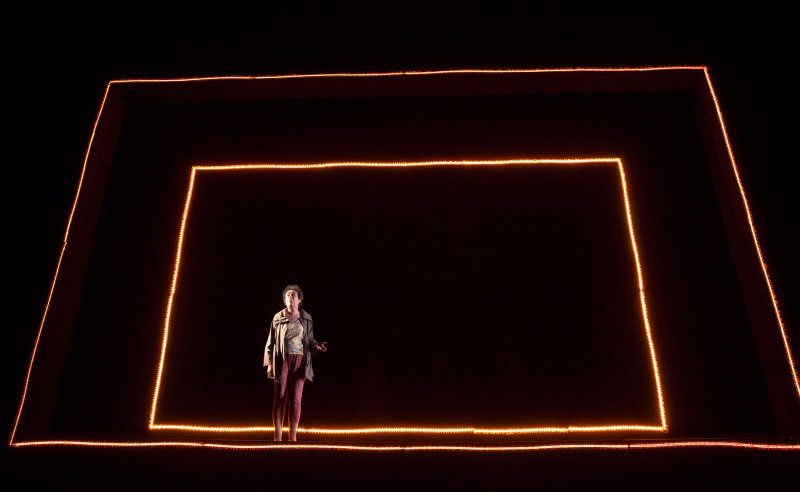

These passages are indubitably different from the more intimate and pedestrian language that dominates the rest of the play, and it is presumably for this reason that accomplished director James MacDonald elects to isolate Mrs. Jarrett within a garishly illuminated orange frame on the threshold of the proscenium when she intones them. This decision has a number of unfortunate consequences. As compared with her compatriots, Mrs. Jarrett is endowed by the production with a certain unwarranted sibylline gravitas. The others are figures of pathos, but she is presented as speaking the Truth. Such a distinction is not suggested by anything in Churchill’s text, and its heavy-handed insertion undermines the play’s quietly overwhelming assertion that the parts of ourselves we make legible to others constitute only a tiny fraction of what is worrying our shuddering souls at any given moment. Reciprocal benign neglect prevails and we are, at best, alone together.

One can imagine inferior versions of Escaped Alone peopled by different demographics, a version with four young men preoccupied, perhaps, by sex and ambition, but Churchill, herself in her seventies, seems to share Maeterlinck’s conviction that those most closely adjacent to life’s great thresholds of knowing, birth and death, possess a kind of sixth sense, an otherworldly understanding of the strangeness and fragility of existence, and it is this understanding she generously chooses to impart.

Escaped Alone by Caryl Churchill

Directed by James MacDonald

Brooklyn Academy of Music, Harvey Theater

Brooklyn, New York

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jessica Rizzo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.