Networking is both motif and method in the work of River Lin (林人中). Performing, directing, curating, and living between Taiwan and France, he has established himself as a facilitator for trans-local and transdisciplinary ways of artistic engagement and communication. While playing and juggling multiple roles himself, it is the historiography of performance art that remains one of Lin’s main concerns, which he consequently strives to address both in his own creations and by relating to others’ works as a curator.

Taiwan has been praised for its highly effective Covid-19 response. Only as part of precaution measures, from April to June 2020, theatres and movie houses had to keep temporarily shut. During this time of spring, Lin found himself experiencing a period of hard lockdown in France, where he based himself a few years ago. From his Paris apartment, Lin initiated a lecture series to reach out for discussion with fellow artists and performance makers from the Sinosphere. He suggested a format of 6 takes (“Expanded Choreography”, “Participation and Situation”, “Theatre of Things”, “Expanded Cinema or Cinematic Performance”, “Musical and Sonic Exhibition”, “Lecture Performance”) to collectively rethink both the transnational turn in (Chinese) performing arts production, as well as the performative turn in the visual arts, which led to the immense popularity of performative concepts being part of global Biennales and exhibition programs of the past decade. For Lin, this initial online sharing series functioned as a trigger to work on concepts that came to be realized later this year, two of which – FW: Wall–Floor–Window–Positions and Dancing with Gutai Art Manifesto 1956 – are discussed in this article.

Back in 2017, together with the Taipei Performing Arts Center (TPAC) and the Taipei Culture Foundation, River Lin initiated ADAM – Asia Discovers Asia Meeting for Contemporary Performance, an Artist Lab taking place in Taipei each summer. This Lab offers a two-week residency program that (in non-pandemic times) invites artists from across Asia and beyond to collectively invent new projects. The focus of this gathering lies on extending the possibilities for artistic collaboration and growing an interface between artists and performing arts markets. For its first three editions, ADAM has welcomed practitioners from all over the Asia Pacific region to Taipei to join the program composed of workshops, talks, lectures, and performances.

In 2020, also known as “the year of the pandemic”, the fourth edition of ADAM was held in virtual space, as most of the invited artists were unable to travel to Taiwan in the summer. By moving the ADAM program online, TPAC decided to offer a communication channel, progressively working on finding formats against pandemic fatigue. The curatorial concept hence aimed to expand the usage of the virtual stage of the video conference platform, to question the notion of performativity in such an online setting. For one part of this program, the invited artists were asked to revisit Bruce Nauman’s 1968 work Wall-Floor Positions and share their performative enactment via their screens with each other and the audience. This time of live-streaming culture, with artists sharing their live-practice online and in real-time, marks a great shift to Nauman, who had staged himself for the film camera in an isolated studio setting. Nauman’s conceptual approach towards dimensioning (wall) verticality and (floor) horizontality by means of the body was taken on by the ADAM artists, to be transferred into the frames and framings of, what the curator’s proposal called ‘Internet Architecture’. This cyber-revisiting of Wall-Floor Positions was aided by the metaphor of window(s) and given the expanded title FW: Wall–Floor–Window–Positions. It took place in three online sessions. A closer look at selected contributions introduces some of the concepts presented.

Screenshot from ‘ADAM 2020/ FW: Wall-Floor-Window Positions I‘

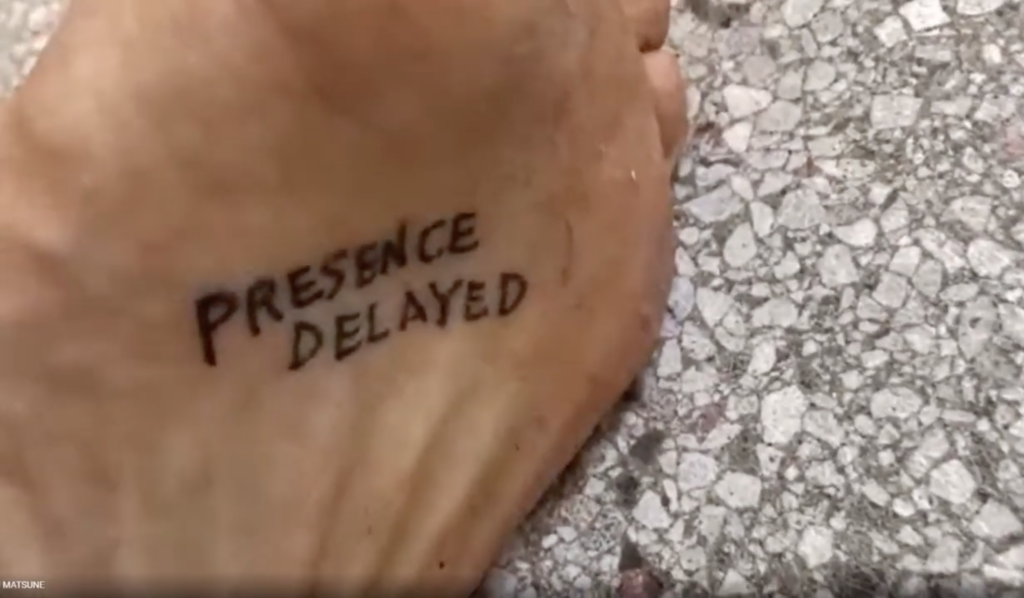

Departing from Nauman’s work, artist Joel Bray as well as the duo of Xiao Ke x Zi Han both used screens to relate Nauman’s figuration of the intermedial window to how the lenses of our computers, tablets, and phones now duplicate, and as consequence remediate and compress our bodies. Tokyo-based dancer and performer Takao Kawaguchi poetically arranged reflecting materials for the camera, composing elements that he had used in previous performances, which are now kept in his studio in Japan. Scarlet Yu shared a rather private view into her new life with a newborn and opened up to questions of motherhood, which, sadly, are still rarely discussed in the works of performance artists. Within the wide spectrum of practices that came to be presented, some artists also seemed to respond in their own and unique ways to the predicaments of being asked to publicly stage themselves in their actual living spaces. To film his contribution, Michikazu Matsune (Japan/Austria) used a hand-held camera to only show his feet while walking barefoot across terrazzo-floor and presenting messages such as ‘presence delayed’, written across his skin. The obfuscating angle of the camera led him to deconstruct the geometry of space in favor of a focus on the living and communicating body. By keeping further characteristics of the physical space outside the frame, he enforced both a strange sense of disorientation and yet an intimate feeling of physical closeness.

Screenshot from ADAM 2020/ FW: Wall-Floor-Window Positions I (Michikazu Matsune)

Questioning different understandings and approaches to performativity makes one point of departure for collaboration in the ADAM Artist Labs. This fourth edition not only shows how the identities of artists, their practices, and the existence of an audience are quintessentially relevant for creation but emphasizes the quality of spatial configurations for and within artistic processes. After each online gathering and individual presentation, a communal sharing concluded the event. Despite that these split-screen dialogues can hardly be called “artist talks” (or Q&A sessions, as such are common practice both after real-world film and theatre showings), the program of ‘Internet Architecture’ was discussed in relation to how online space can be shared. It presented the audience with performers’ bodies, trying and achieving to “get in touch” with each other, managing to find different ways to work with and around technology.

Screenshot from ‘ADAM 2020/ FW: Wall-Floor-Window Positions I‘ (Joel Bray).

As of now, with most places in this world still having people experience their realities within the limitations of pandemic conditions, it is yet too early to claim enough critical distance as a modus operandi for evaluation and comparison of those (perhaps nothing but substitute) practices, especially in regards to their social impact. It can be commented, however, that their ways of engaging with the trope of space make a great difference to how online space was imagined just one or two decades ago. Mainly in genres of Internet-, Post-Internet and Media Art of the late 1990s and early 2000s, artists illustrated virtuality in neon-colored, glitchy aesthetics, producing images of cyberspace that depicted vast and “open” digital landscapes. ‘Internet Architecture’ in ADAM offered to experience digital space as a place of embodied inter-and intra-action in real-time instead. The anthropometric scale of domestic space also raised questions on how the body is staged and tamed in social media live-streaming culture.

In terms of live-art production, these recent times have seen significant confusion in project planning, mirroring the impact of the pandemic across all arts sectors. Following his return to the island of Taiwan in summer and serving as curator for ADAM, Lin decided to work on a live performance that had originally been commissioned by the Tokyo festival and then got postponed to an uncertain date. Together with a group of performers, he decided to realize Dancing with Gutai Art Manifesto 1956 in Taiwan instead. The five-hour durational performance premiered on 18 November 2020 as part of the exhibition Re: Play in Taipei’s C-Lab and presented the artists’ emphatic exploration of Japanese post-war performance art.

“Dancing with Gutai Art Manifesto 1956” (2020)

Source: https://riverlin.art/Dancing-with-Gutai-Art-Manifesto-1956

Gutai is one of Japan’s pioneering art collectives, founded in 1954 by Yoshihara Jiro in the Osaka-Kobe region and sparking discussion and controversy over a long period until it dissolved in 1972. ‘Gutai’ translates as ‘concreteness’ and articulates one of the group’s most distinctive traits – their desire to physically engage with an extraordinary range of materials. Artists attached significance to the process of performativity in creation, giving special attention to the body’s interaction with the environment. This included a range of media such as painting and film, but also less conventional materials such as the infamous light-bulbs in Tanaka Atsuko’s dress, or mud in the experiments of Shiraga Kazuo. Paintings and other material traces created during this performance were later displayed in the museum space, echoing Gutai’s ‘scream of matter.’ A great deal of fascination for collective artistic endeavors such as the Gutai movement or Black Mountain College, where artists were busying themselves with similar questions at a parallel moment in time, stems from an auratic interpretation of their decision to work outside capital cities, focusing on new relations between art and everyday life. In reference to Gutai, Ming Tianpo has titled this ‘collective spirit of individualism’, as the artists, despite engaging in greatly heterogeneous practices, decided to involve themselves in a collective enterprise that encompassed their exhibitions, publications, and discourse.[i]

In an attempt to revisit the historic works, Dancing with Gutai Art Manifesto 1956 extracted parts of the manifesto to be developed into a working score. The Taiwanese performers further studied the archives from Gutai’s artists Tanaka Atsuko, Shiraga Kazuo, Murakami Saburo, and Shimamoto Shozo among others, to revisit them with methods of “expanded choreography”. This term has become synonymous with structures and strategies that depart from subjectivist bodily expression, style, and representation – transforming the possibilities of choreography from referring to a set of protocols to be understood as of an open cluster of generic tools.[ii] During the performance in C-Lab, movement, language, and material became the artist’s channels to access the archives of various members of Gutai Art Association and develop sensitivity in relation to understanding certain similarities of their methods. Dancing with Gutai Art Manifesto 1956 presents the historic movement of Gutai as the beginning of performance art history in Asia. The performance achieves to highlight the importance that the artists associated with the group placed on finding formats for artistic exchange and engaging with different audiences, especially to facilitate presenting themselves outside Japan.

Dancing with Gutai Art Manifesto 1956 (2020)

Source: https://riverlin.art/Dancing-with-Gutai-Art-Manifesto-1956

The Gutai movement topically anticipated what Lin’s work is committed to in the long term: To promote an understanding of performance art in East Asia, especially Taiwan, as part of global performance art history. Lin’s overall body of work is concerned with an examination of the genre’s legacy in an Asian ‘context’, as he himself states,[iii] expanding an understanding of how performance art historiography, too, is haunted by the ghosts of Western-centrism. Both his take on positioning the artistic direction of ADAM and his own performances demonstrate an effort towards redefining community as a horizontal and creative collective, not only by exploring the dimensions of (artistic) exchange as an abstract theme but also striving to facilitate long-term collaboration between Asian artists, as methods of working and presenting.

We see Lin pathing ways into the genre’s histories, as he traces and mobilizes innovative collaborative frontiers with respect to an artist’s self-organization and autonomy. His curatorial and artistic practice presents a non-dichotomous engagement to focus on the globally traversing history of the genre. Such an approach calls on the archaic connotation of ‘traversing’ as opposing, debating, or disputing,[iv] as it offers spaces to discuss how we, as human beings, can approach each other and resonate with one another. Lin himself borrows the terminology of queerness and queer practice when organizing his works, ranging ‘from Tanaka to Nauman and back again into “Queering Body Archives.”[v] By placing emphasis on the notions of context and resonance, rather than stressing narrow national or continental settings, dichotomies of East and West are left aside. His curation of the upcoming 2021 edition of ADAM foresees, in addition to a Taipei-based artist lab, again an extended program for online audiences as an invitation to collectively rethink and reframe those windows, which allow us to meet.[vi]

[i] See Ming, Tianpo. 2013. “Gutai Chain: The Collective Spirit of Individualism.” positions: asia critique. Volume 21, Number 2, (Spring): 383–415.

[ii] See “Conference on Choreography as an Expanded Practice”. MACBA Barcelona, 29-31 March 2012. Accessed 10 February 2021. https://choreographyasexpandedpractice.wordpress.com/.

[iii] Interview with River Lin via Zoom, 28 November 2020.

[iv] See Ferrari, Rossella. 2020. Transnational Chinese Theatres. Intercultural Performance Networks in East Asia. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 17.

[v] See Lin, River. “Queering Body Archives”. Artist Website. Accessed 10 February 10 2021. https://riverlin.art/.

[vi] See “ADAM 2021 preconcept”. ADAM Website. Accessed February 10 2021. http://adam.tpac-taipei.org/en/news.aspx?id=22&fbclid=IwAR1-5FnOal_39uhMtX3XqTirDuF9WGFTO1x-9YgFSgiIKH0StPDcBsodmLM.

Freda Fiala is a researcher and writer, focusing on performing arts cultures and arts networks in contemporary East Asia. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Vienna and a Fellow of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. She studied Theatre, Film, and Media Studies as well as Chinese Studies in Vienna, Berlin, Hong Kong, and Taipei. She has also earned experience working for various theatre institutions and festivals such as Vienna Festwochen, Salzburg Festival, Berliner Ensemble, and Taipei Fringe Festival.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Freda Fiala.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.