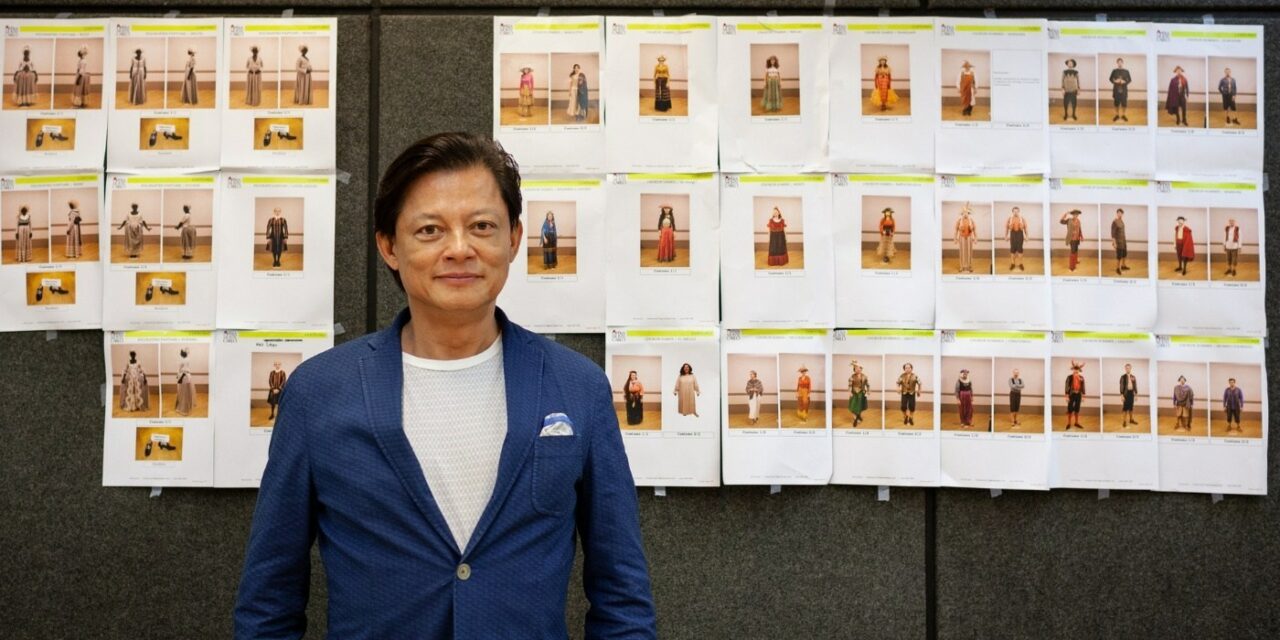

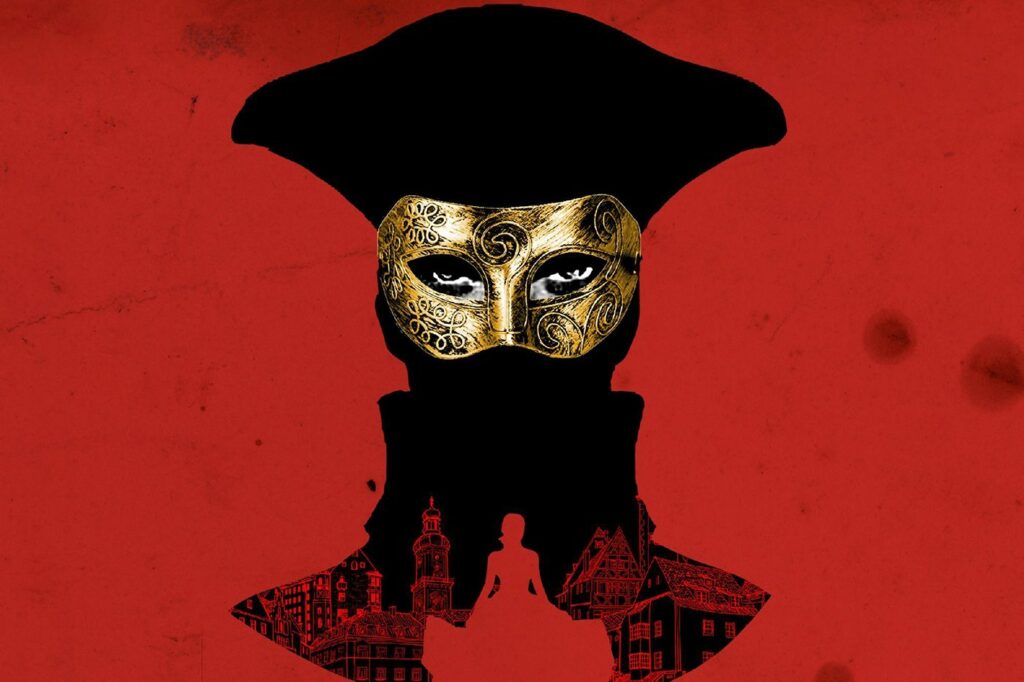

Being one of China’s Three Tenors meant that Easter was no holiday for Warren Mok. The opera giant flew back just days ago after performing Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera at Beijing’s National Centre for the Performing Arts. In less than a month’s time, Opera Hong Kong, the organization he founded in 2003 and where he now serves as artistic director, will premiere another celebrated opera: Don Giovanni.

Composed by Wolfgang Mozart, the opera tells the legend of Spanish libertine Don Juan, who murders and womanizes until he is doomed by divine punishment. Rarely matched as an example of the genius way Mozart treats dark subjects such as human vice through comedy, the opera buffa has remained one of the most widely performed operas in the world since its premiere in 1787.

Surprisingly, Hong Kong has rarely staged this magnum opus, except for the 2006 production at the Hong Kong Arts Festival. “It has exceptionally ravishing arias and ensembles,” Mok says. “It’s high time that Opera Hong Kong brings it to the Hong Kong audience again.”

Mok has had a similarly long journey. “I started as an apprentice, playing minor characters who died early in the operas!” He recalls with pride, noting that he once performed in Don Giovanni. But it wasn’t the Iberian womanizer that lured the Beijing-born, Hong Kong-raised tenor into the world of opera. He watched his first opera at the age of 18 when he was an undergraduate at the University of Hawaii. “I was absolutely mesmerized by the tenor’s powerful voice,” he recalls. “Imagine sitting in a two-thousand-seat auditorium and the singer didn’t need the microphone to project his voice.”

Dazzled by the opera singer’s vocal sublimity, Mok was determined to tread the path of a musician. Until then, his path seemed predestined: Mok is the descendant of Mok Sze-yeung (1820-1879), who established a three-generation line of compradors for the Swire Group. But the family business didn’t call out to him as much as opera did. Mok went on to pursue a master’s degree at the prestigious Manhattan School of Music in New York before perfecting his vocal skills as an understudy of the late Italian operatic tenor superstar Pavarotti in 1987. He made his European debut the same year at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, one of the top ten opera houses in the world.

Mok became a sensation, no doubt because of his vocal virtuosity, but equally so for being one of the first few Chinese singers of classical Western opera to reach international status. One might think that Hong Kong could hardly be associated with an art form that originated four centuries ago in the Republic of Venice, but the tenor begs to differ.

When asked why opera matters to a modern city half a planet away from opera’s origins, he declares, “Opera is an international art form. To think that it only belongs to the West is backward. Although it stemmed from Europe, it doesn’t belong to any city or nation. Take a look at other international major events like the Olympic Games. How many sports were invented by the Chinese? Zero! Still, why do we participate in it? Because it belongs to the global arena. Hong Kong claims itself to be an international cultural hub, but without opera, it would just be an empty title.”

Mok insists that opera has the potential to “bring cultures together,” which is particularly relevant for a global crossroads like Hong Kong. At the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II at London’s Royal Albert Hall in 2013, Mok performed Capurro’s famous “O Sole Mio” as well as a version of Chinese folk classic “Fengyang Flower Drum” adapted to the Western opera singing method.

“It was through opera that I introduced my Chinese culture to the Queen, who loved the song even though she didn’t speak the Chinese language,” he says.

Hong Kong’s ties with opera trace back to the British colonial era and the Hong Kong Arts Festival has organized two opera productions annually since its inception in 1972. “But that’s not enough for the seven million people,” Mok insists. He notes that the Urban Council (a kind of municipal government that was dissolved in 2000) organized individual opera productions, but there was never any sustained long-term support for opera. That’s what prompted Mok to set up Opera Hong Kong in 2003 as the city’s first non-profit opera organization.

Since then, Mok and his small team of seven people have been the pillar of support for Western-style opera in Hong Kong. Every year, they stage two major performances and one opera in concert (meaning operatic singing in its purest form, stripped of sets, costumes and accouterments). In 2015, they also launched the Jockey Club Opera Hong Kong Young Artist Development Programme, the city’s first-ever intensive professional opera training programme, in addition to regular summer camps, master classes and school tours, during which Mok’s team stages 30-minute operas in local schools.

“It gives me great satisfaction to read school children’s reports that they thoroughly enjoyed our performances,” says Mok. “Whether they end up with a career in opera is their future decision, but the point of promoting opera in schools is to culturally nurture Hong Kong’s young generation from all social classes. Opera is no longer exclusive to the elite. It’s for the masses.”

Sixteen years of his hard work have paid off. “There’s a big jump in local opera audience size,” says Mok. “Tickets to our Carmen production is constantly sold out, and 90 percent of our seats for the last Turandot show were taken. Previously there were only two annual productions in the city – now there are at least seven or eight productions every year by us, Hong Kong Arts Festival and other art groups.”

Compared to other cities, the audience for opera in Hong Kong is relatively young, at around 30 to 40 years of age. Mok attributes this to Hong Kong’s Westernised education, a legacy of the colonial period, as well as the city’s exposure to Western culture. “Hongkongers are by no means strangers to bel canto – ‘beautiful singing’ in Italian,” he enthuses.

One of Don Giovanni’s local cast members, soprano Louise Kwong, recently won the Hong Kong Arts Development Council’s Award for Young Artist. Now she is performing internationally – “the first and only young Hong Kong opera singer to perform in a first-rate opera house overseas!” exclaims Mok.

He expects Hong Kong to exert even more of an influence over opera in the future. More and more, there is a push to create original operas infused with Chinese story elements and singing techniques, such as this year’s Hong Kong Arts Festival production of Madame White Snake, a Western opera adapted from one of China’s four great folktales.

“These contemporary operas are different from Chinese opera, for these productions are still sung with the bel canto method,” says Mok.

Adapting Chinese lyrics to the Western style is no easy task. “We have to adjust the way we sing and enounce Chinese words, which is a new realm of study.”

As much as he is open to innovation, however, Mok says Don Giovanni will remain faithful to the original. “It’s not necessary to add regional-specific elements to a classic piece of opera just for the sake of doing it,” he says.

What he instead underlines about making opera in Hong Kong is its internationality. “In all Opera Hong Kong’s productions, our team consists of individuals from various cultural backgrounds,” he says. “We collaborate with both foreign directors, conductors, singers, stage designers, as well as local orchestras, choirs and costume makers.” Don Giovanni features Latvian conductor Mārtiņš Ozoliņš, Monacan director Jean-Louis Grinda, American bass-baritone Richard Ollarsaba.

Mok further underlines how Don Giovanni resonates with the contemporary era. “Mozart was absolutely a visionary ahead of his time,” he says. “He boldly shed light on sensitive topics such as gender 200 years ago, and today we’re still discussing the subject. Look at the global #MeToo movement. Don Juan the philanderer is basically the central figure of denouncement. He would have been imprisoned!”

Going forward, Mok has even bigger plans for opera in Hong Kong. “Apart from directing existing operas, I wish to produce our very own original production about Hong Kong in the coming one or two years,” he says. “I also urge the government to complete an opera house in the next five years, and I hope Opera Hong Kong can be the organization-in-residence to further our work.”

This article originally appeared in Zolima CityMag on May 6, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zabrina Lo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.