Vwayaj, “Voyage” in Haitian Kreyol, a dance performance split into two movements of three pieces each, is an enthralling piece of work inspired by Haitian dance traditions and by anxieties of immigration. Choreographed by Jean Appolon, and performed by his company of six racially and stylistically diverse dancers, Vwayaj is a re-imagining of Appolon’s 2017 performance, Lakou Ayiti, “Haitian Homecoming” in Haitian Kreyol. Vwayaj was in residence at Boston’s Lyric Stage for a short run from June 10-June 22.

The six dance pieces in Vwayaj are centered around Haitian immigration to America. The dances blend celebrations of heritage with the fear and doubt that come with living in a new country. Audio of a personal immigrant story plays during one piece, while a video interview of an immigrant reflecting on her experience plays during another. Both stories emphasize the contributions immigrants made to the United States while challenging the stereotype that immigrants are here to ‘take away’ from those born on American soil.

Jean Appolon’s choreography is built on repetition and flow. The six-member company of Jean Appolon Expressions (JAE) will surge into a collective unit, before suddenly ebbing back to an individual or paired movements. Dancers pulse aggressively near the earth and leap gracefully into the sky. Moving in and out of this space, Vwayaj makes for a trance-like experience and emphasizes the comings and going inherent in immigration.

Mcebisi Xotyeni in Vwayaj. Photo Credit: Matt McKay

The dancers themselves are all strong, as they must be for this physically demanding show. However, each brings their own individuality to the performance. South African Mcebisi Xotyeni is sharp, Boston born I.J. Chan is fast, Californian Lonnie Stanton is smooth. When the dancers are all in unison, these personalities are apparent. The piece is less interested in creating a unified whole, and more interested in stressing the individual needed to cultivate a diverse group. Further emphasizing the single person are the graceful costumes, also designed by Appolon, each made slightly distinct for each dancer.

In the second half of the performance, director and choreographer Jean Appolon steps in to perform a solo dance. He’s less practiced than his dancers—he admits in a post-show conversation that he hasn’t performed in years and was reluctant to return to the stage—but Appolon’s piece carries a maturity and gravitas thanks to his years of experience and deep passion for dance.

As in the first movement, a video plays during a dance break: a photo montage of Haitian beaches followed by a film of Haitian protests. The film is powerful and reminds why Haitians are leaving their country, but the photos, which include several images of tourist resorts, feel like a travel agent’s advertisement.

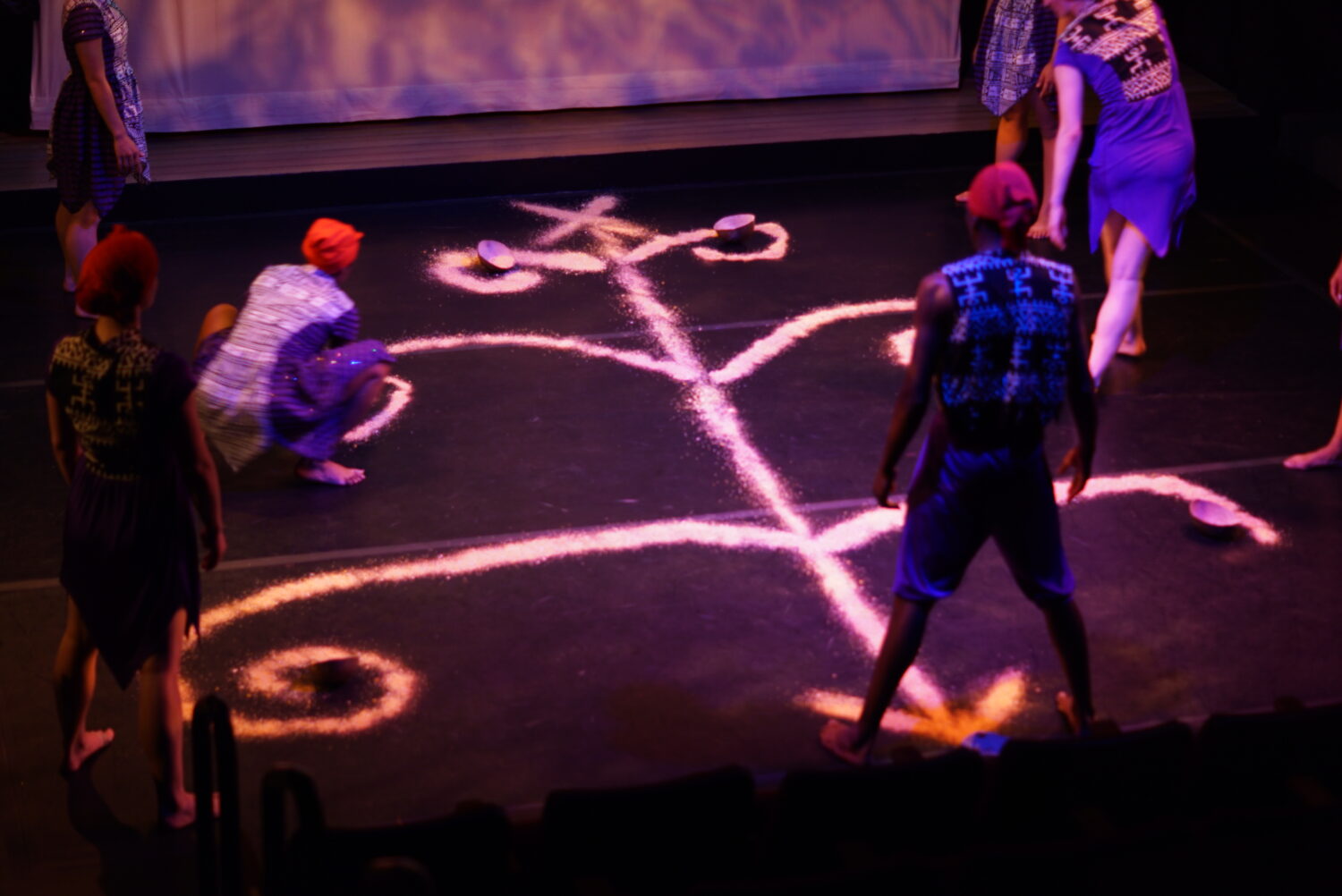

The company of Vwayaj. Photo Credit: Matt McKay

Music is a key part of this performance. Val Jeanty, a Haitian electronic musician, mixes and plays her music live while accompanied by the procession—drums, chimes, rainmaker—of Wichemond Thelus. Jeanty and Thelus too are apart of the performance, responding to the dancers on stage, smiling and nodding to the beats.

In the final dance piece, the performers, still dancing, create a large tree-like symbol on the ground by pouring sand on the stage. Jean Appolon says this symbol represents power and healing; he likes to end all of his shows with this symbol. It’s appropriate. Vwayaj is a powerful show. It’s a healing salve that doesn’t ignore pain, a reminder of togetherness while remaining true to oneself. A performance that shows through movement how immigrants can make a country rich in spirit.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rem Myers.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.