Opera is filled with tales of violence. Its whole history relies on great passions tragically predetermined by social inequalities. These are usually crueler and more exclusionary towards women and other minorities occupying symbolically weaker positions of power.

In this sense, popular Western opera librettos represent various acts of sexual repression. Great opera heroines like Carmen, Medea, Turandot or Mimi feed our imagination. Their embodiment of tragic tensions arises precisely from their sexuality that cannot be positively accommodated in existing social structures. The conflict and proximity between female desires (not only sexual) and death show the extent to which our culture is founded upon the exclusion of the integrity of the female experience. The Western opera tradition chose love as its vital theme and has primarily focused on relations between the sexes. Thereby, it has shown great creativity in constructing models for Western intimacy and understanding. However, when studied carefully, it simultaneously forms this intimacy’s most significant criticism.

Unknown, I Live With You by Katarzyna Głowicka and The Airport Society. Photo by Camille Cooken.

No opera heroine sings an affirmation of her positive experience. In this context, The Airport Society collective’s founder Krystian Lada’s decision to take the extraordinary texts written by contemporary Afghan female poets – under a pseudonym and in a politically restricted situation – and adapt them into an opera seems extremely strong. Lada – a director, librettist, dramaturg, and music activist – repeatedly insists that correcting historic operas is not his aim. Instead, he is interested in a musical spectacle that can address issues relevant to and posed by the contemporary world, showcasing the full potential of operatic expression and revealing its radical and subversive powers.

Unknown, I Live With You by Katarzyna Głowicka and The Airport Society. Photo by Camille Cooken.

The texts adapted for the Unknown, I Live with You libretto was written by female poets from Afghanistan during the peak of the Taliban regime’s political supremacy. The regime created a cruel social hierarchy categorizing people according to their sex and stripped women of their public rights, including the rights to education and creation. The authors, known as Roya, Meena Z., Fattemah AH, and Freshta, conceived their poems during clandestine creative writing workshops under the Afghan Women’s Writing Project. The program is supported by activists from local organizations like RAWA, Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan.

The texts combine great simplicity with powerful expression. Confronting a typically Western ‘high-art’ music form with the power of resistance to the fundamentalist, religious retrotopia – which literally realizes the fundamental patriarchal idea of the inferiority and serfdom of women – says a lot about the present. It emphasizes the continuum of the precarious conditions of women under social orders founded upon patriarchal ideas of religion. It creates a sense of solidarity and, at the same time, an awareness that every broadening of freedom creates necessities for new responsibilities and new strategies of resistance. “Unknown, / I learn from you / the language of love / you learned from your mother,” writes Roya. Unknown, because un-understood, is both a form of exclusion silencing women and the power of expression between women that the poem reveals.

Unknown, I Live With You by Katarzyna Głowicka and The Airport Society. Photo by Camille Cooken.

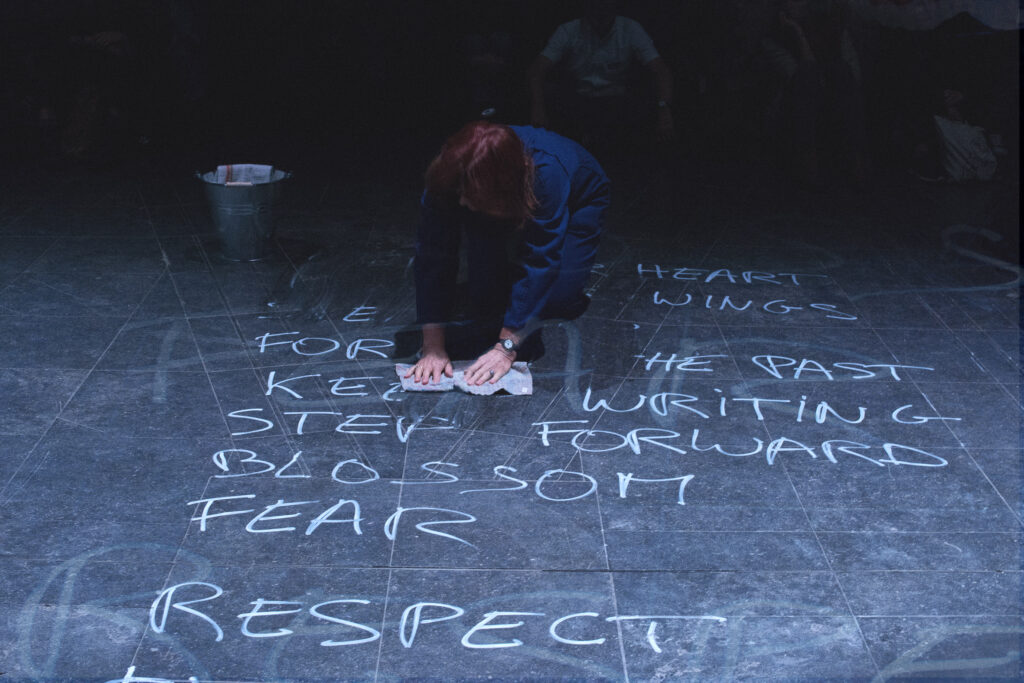

“Damn you God (…) / For building a wall in front of my will” marks how contradictions in a traditionally elevated religious order – understood as a repressive political program – cruelly demotes women. “If I were not a woman / Aaa / the day I was born / Aaa / My mama would not have suffered (…) If I were not a woman / I could wear the light colors I love and drive the car if I wished to / I could marry my girlfriend.” Women’s desires in all their diversity are relegated to the ‘unknown’ space, revealing how ambivalent the experience of physical and symbolic violence is. “Women of the world / Where are you? / Can you hear me? / Help me / Before I’m forced to / Bury my work. / Let me write my last poem.” Writing, threatened by the ultimate punishment, becomes the ultimate gesture of resistance, as well as a provocative message to and for other women.

Roya’s poems are accompanied by harrowing works by Freshta. She describes a little girl’s dream to participate in a school sports competition; a bomb attack breaks the dream (“I Thought It Was a Dream but When I Woke, I Couldn’t Walk”). Freshta also exposes the scale of humiliation and internal destruction caused by rape and sexual violence in prison (“Sexual Assault”). Meena Z’s quiet complaint again focuses on the ambivalence of enslavement: “When / my heart begins to open / Something / closes it with fear (…) When / I start to blossom / Something / keeps me captured.”

A recurring desire for community amongst women – and particularly an affirmation of mother-daughter relations as an outline for an alternative world with more empowering and open values – dominates here. Fattemah AH writes: “I feel something strange inside me / The days are more beautiful (…) I feel you inside me, my daughter – moving.” The text’s metaphor of blossoming is striking as an attempt to respond to oppression through a different understanding of that which is bodily, organic, and gives a sense of permanency and infinity. The Afghan poets’ defiance is not only an act of writing that can become a death sentence. It is not only a report of a crime committed by a political regime creating a retroactive order that is violent towards women and, by being so, exposes its primitive weakness. Most of all, it is the germ of a project for a new world, a world that gives back active power to women’s desires.

Unknown, I Live With You by Katarzyna Głowicka and The Airport Society. Photo by Camille Cooken.

Even though the act of writing could send them to their deaths (today’s regime is less radical, but the situation of women improves very slowly), the poems by the Afghan poets inscribe themselves powerfully within the well-known Western Horatian topos “non omnis moriar” (“I shall not wholly die”). Their writings add to this famous theme a ban-breaking element, reaching from a place of a complete exclusion for an ‘immortal’ means of expression like poetry. The women’s pure poetics and ascetic stylization confront the scale of political violence in their fates.

Composer Katarzyna Głowicka’s music responds to this perfectly: it is designed to express the monotony of oppression and the explosive moments of revolt. The sounds of the string quartet and live electronics interact through unsettling contradiction, playing out the story of abuse and vulnerability. In doing so, they push their performance towards a hymn that surprises with the tenderness and intimacy of the experience of fighting violence. “Unknown, I Live with You,” divided, fragmented, and perhaps with something killed inside me. However, my experience will always remain in you. It is uniquely carried by the statuesque and emotional voice of Polish opera star Małgorzata Walewska. Her performance brings an overwhelming sense of despair but also a peculiar tenacity. Californian singer and transgender woman, Lucia Lucas offers a rare and brilliant bass-baritone that intertwines with falsetto in a vital dialogue between a victim and executioner, bringing the disturbing effect of a disjointed and broken narrative. With her soft and captivating mezzo-soprano, the African-American singer Raehann Bryce-Davis goes beyond complaints and sufferings, and finally unites the tensions of this excellent dramaturgy in her song of freedom and inspiring dream.

Unknown, I Live With You by Katarzyna Głowicka and The Airport Society. Photo by Camille Cooken.

The opera-installation Unknown, I Live with You offers an interweave of sex, oppression, and singing that renews or shapes new traditions of opera. By performing various perspectives of minorities, its female heroines paradoxically not only sing their independent integrity and act out their intimate (hi)stories, they also become active agents of a larger, communal history. By doing so, they profoundly change this history’s deeply moving significance.

Listen to selected songs from Unknown, I Live With You.

Upcoming performances of Unknown, I Live With You:

31st January 2020 and 1st of February 2020 at the Opera Rara Festival (Małopolski Ogród Sztuki, Cracow, Poland)

29th of February 2020 (two performances) at the Kurt Weill Fest (Marienkirche, Berlin).

This article was originally published by The Airport Society on May 15, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Agata Araszkiewicz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.