Peta Brady’s Ugly Mugs, which I saw in Sydney last week, opens with a gurney being wheeled onto the stage – on it, a sex worker who has died at the hands of a client and who, like the phoenix tattooed on her chest, rises from the ashes to tell her story. The play draws heavily from accounts of rape, coercion, and trauma recorded in a crime prevention initiative of the same name.

The “Ugly Mugs List” is a closed publication created by the former Prostitutes Collective of Victoria in 1986 to inform sex workers about abusive clients so that they might avoid victimization.

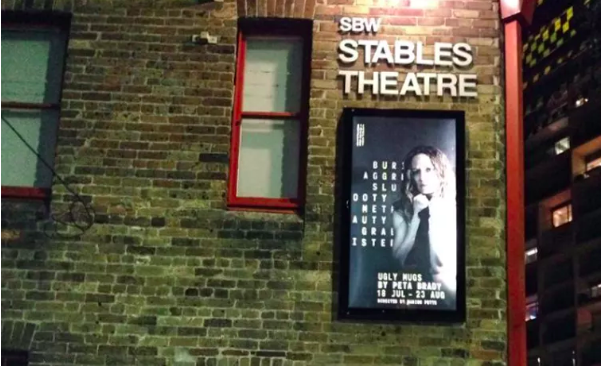

Currently playing at Sydney’s Stables Theatre, Ugly Mugs launched at Melbourne’s Malthouse Theatre in May. The play has been celebrated by critics for giving voice to the victims and for forcing audiences to confront aspects of society we’d rather avoid.

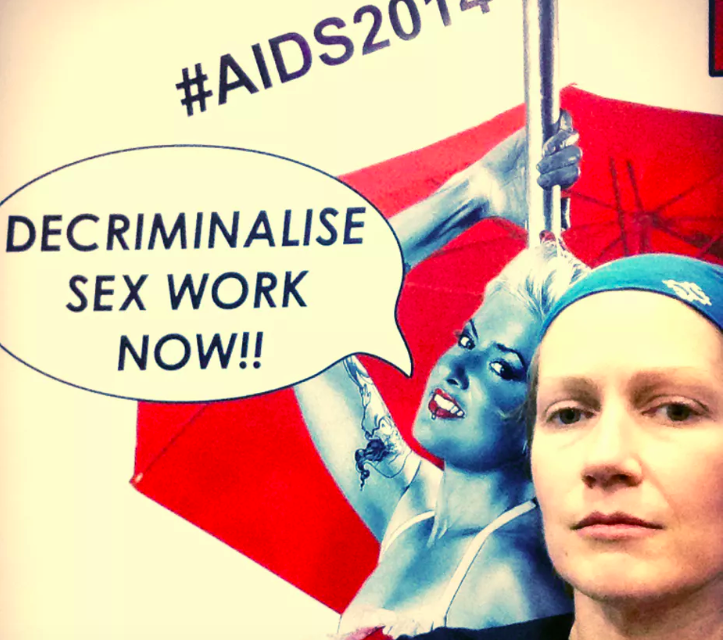

Sex workers themselves have taken a different stance, raising important questions about the play’s appropriation of authentic narratives and, in turn, the double victimization of an already marginalized community. This week their concern has received widespread media attention. In the wake of much criticism, Griffin Theatre has insisted that the testimonies in the play are “complete fiction.” Director Marion Potts has also responded, stressing that the production is “a work of fiction”.

I spoke to Jane Green, from Victoria’s Vixen Collective and the Scarlet Alliance, both sex worker organizations, about Ugly Mugs.

Leslie Barnes: Sex workers negotiate consent with the client at the start of every transaction. How was consent negotiated for the fictionalization of these narratives? And how have sex workers in Melbourne and Sydney responded?

Jane Green: Brady used a closed resource intended for sex workers only as “inspiration” for Ugly Mugs–this is an unacceptable breach of sex workers’ privacy and trust. Ugly Mugs is an exploitation of sex workers by presenting stories of violence against them as entertainment to be consumed by the general public.

There was no consent negotiated at any point. Vixen Collective found out about Ugly Mugs when it was in rehearsals and immediately raised objections. Many others found out through social media later, and their anger has been profound.

Sex workers who saw the play in Melbourne were disturbed by the scene where “Working Girl” attends her own autopsy. They were also outraged to see a character read from the “Ugly Mugs” on stage. One sex worker from Sydney described it as “just another dead hooker on a slab” and was “glad to be near an exit”. Many have complained that the autopsy scene, in particular, caused them a great deal of distress.

Ugly Mugs at Sydney’s Stables Theatre. Vixen Collective Archives

LB: How have the concerns you’ve raised been received?

JG: Vixen Collective met with Malthouse while Ugly Mugs was in rehearsals, and we expressed a range of concerns, specifically about the “pity porn” narrative. We spoke to them about the breach of trust and warned that the show would perpetuate stigmas against sex workers. Our concerns were dismissed.

Scarlet Alliance met with Griffin Theatre in Sydney and emphasized the fact that the play was taking a closed resource before a public audience. Prior to this meeting, Griffin Theatre made written inquiries to Scarlet Alliance about the NSW “Ugly Mugs”, then requested a copy in the meeting.

Sex workers have since raised the issue on social media, and Griffin Theatre released a statement in response. But they’ve still failed to respond to sex workers’ key concerns.

LB: What do you mean by “pity porn”?

JG: Ugly Mugs has left audiences and reviewers with false impressions of sex workers as one-dimensional victims, which is far from the reality of sex workers as whole people with agency.

Diana Simmonds, for example, concludes that we are: “utterly desperate for a dollar.”

The depiction of sex workers as helpless, desperate stereotypes rather than as workers fighting daily for recognition of their human rights and labor rights–this is “pity porn.”

LB: Brady has experience as a drug and safety outreach worker in St. Kilda. How has this experience shaped the play?

JG: Brady’s background is with the Salvation Army, an organization that publically supports the decriminalization of sex work but that continually portrays sex workers as victims in need of rescue. The fact that Brady has worked as a health outreach officer makes her abuse of “Ugly Mugs–allowing non-peers to access it, publicising it, using it as inspiration on-stage–inexcusable.

LB: Some might say the play belongs to a tradition of didactic or political theatre insofar as it seeks to expose its audience to the brutalities sex workers–and women more generally–face. Would you agree that the play seeks to educate?

JG: Sex workers are the educators for and about our community. It’s impossible to educate others about a subject when you are not fully informed. Sex workers do not need non-sex workers to speak on our behalf. Marginalised groups do not appreciate non-peers, coming from a position of privilege, attempting to speak for them.

LB: Do you think it is inappropriate to dramatize or fictionalize sex work?

JG: Media and arts representations of sex workers–and of marginalized groups generally–often perpetuate stigma and discrimination.

Non-sex workers are speaking about a subject with no lived experience to inform what they say. This is why projects like Ugly Mugs are always inherently flawed. If members of a marginalized group are critiquing the way they are being represented in the media or the arts, listen.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on August 19, 2014, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Leslie Barnes.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.