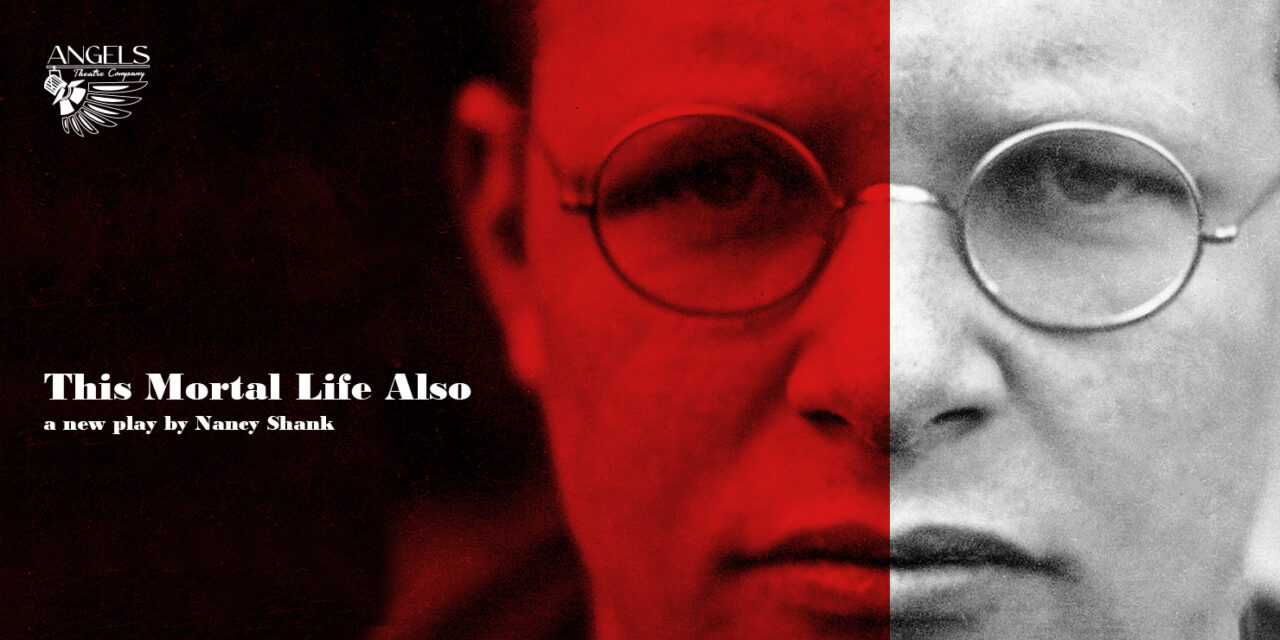

Dietrich Bonhoeffer is not a name typically associated with the theatre. Though the Bonhoeffer family were steadfast supporters and lovers of the arts, the man himself could not be further, in a modern view, from the stage: a renowned German theologian coming of age during Weimar and living in Berlin at the time of the Reich; a man silenced and executed by the Nazis in 1945; a man who has all but disappeared, with the exception of theological studies.

When I was approached by Angels Theatre Company about this project, a new play telling the story of Bonhoeffer and the German Resistance, I hadn’t the slightest clue who Dietrich Bonhoeffer was. I am neither theologian nor Lutheran nor an expert in world religions. What I am, however, is a lover of untold stories and an advocate for those who have been forgotten. Bonhoeffer’s life as portrayed in This Mortal Life Also intrigued me enough to come onboard as Production Dramaturg.

I am so very happy I did. Not only have I developed a fascination and love for Dietrich and his family (and have been reminded of my previous interest in Weimar and the transition), I’ve had the good fortune to work with the most giving, collaborative of playwrights. I am delighted to sit down with her today and chat about her new work, being a (very!) new playwright, and how Bonhoeffer’s story still resonates in the 21st century.

Rhiannon Ling: Hello, Nancy! First of all, for our international readers that haven’t met you yet, can you tell me a little about yourself and your background in the theatre?

Nancy Shank: Sure! I am truly an “emerging” playwright. This Mortal Life Also is the first play I’ve written, so I can’t tell you how thrilled I am that it has found its way to production. However, I have been a longtime theatre patron. I was bitten by the theatre bug when, as a high school sophomore on a French Club trip, I saw the Broadway production of A Chorus Line from the last row of the highest balcony of the Shubert Theatre. Though I hardly knew what I was seeing, I knew I wanted to see more of it.

In high school, I enjoyed attending the professional summer stock performances at Millbrook Playhouse. In college, I loved going to collegiate theatre performances. Later, I played flute and piccolo in the pit orchestra for a number of musicals at the York Little Theatre in Pennsylvania. In Nebraska, my husband, son, and I have loved being patrons of this community’s vibrant theatre scene, particularly the Lied Center for Performing Arts and Angels Theatre Company.

Professionally, I recently retired (early retirement, okay?!) from my administrative and research position at the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center, where I was fortunate to assist local, state, and national organizations, particularly in the areas of community development, information technology, and water resources. I earned a PhD in Human Sciences and an MBA from the University of Nebraska, and a Bachelor’s degree in Urban and Regional Planning from Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania.

Ling: What first brought you to Dietrich Bonhoeffer? What, to you, is so compelling about his life and his story?

Shank: I vaguely knew of Dietrich Bonhoeffer as I was growing up, but I doubted there was anything about the life of a German theologian who lived during the time of National Socialism that would be relevant to me. I had assumed he had survived the war and, in my mind, was complicit in the horrors of the Holocaust. When I learned he had spoken out against the Nazis, my interest was piqued. Then, when I learned he had been murdered by the regime for his involvement in the German Resistance, well, I started reading everything by him and about him.

For me, his story is the journey of who he was before the war—a rising young theologian, a pacifist, someone who was drawn to monasticism, an ecumenist—to who he became: a member of Germany’s Military Intelligence, his cover for the Resistance, and then finally to his involvement in several conspiratorial plots to assassinate Hitler. He left behind many letters and papers, so we can follow his logic as he takes every step, which I find fascinating. Of course, Bonhoeffer is not a single voice crying in the wilderness against National Socialism. Bonhoeffer’s entire family were very early critics of Hitler and they paid the price: four members of the family were murdered by the Nazis for their involvement in the Resistance. Bonhoeffer’s love story with Maria von Wedemeyer, a young heiress, is poignant but irresistible, too.

Ling: What drove you to write a play about Dietrich and the Resistance, instead of something like a book or a publication?

Shank: There is nothing like the theatre to feel the experience of another person. When the house lights go down and the stage lights come up, there is a magic that transports you to other worlds. As I was reading about Bonhoeffer, I was frustrated because there were things about his life I couldn’t entirely piece together emotionally. I felt I was learning about him but not who he was as a person. About that time, I got it in my head that I needed to see a play about him in order to truly understand him. Of course, there were no plays being produced nearby about him, so I got the idea that I should try to write the play I wanted to see. It was very naïve of me: I didn’t even know how to format a script! But I will say that working on this play over the last six years has forced me to really dig into Bonhoeffer’s life, and I do feel like I understand him on an emotional level now.

Ling:Why is it important to tell this story now?

Shank: Bonhoeffer’s story is one of civic courage and moral clarity. He thought very deeply and logically about what was going on in his country and was able to understand that it was leading to unspeakable horror. Crucially, he was willing to take “responsible action,” as he called it. For him, that meant that he must take action based on principles of love, truth, kindness, and faith, that he must understand the consequences, and that he must be held responsible for them. His action wasn’t self-aggrandizing or disorderly. Rather, his actions were done from a deep love for all people, even those who could be considered his enemies. Even when he was in Nazi prison, people recall how he ministered not only to the other prisoners, but also to the prison guards and commandant. That kind of thoughtful courage and love is something we don’t see much of in today’s bitter political divide.

Playwright Nancy Shank. PC: Nancy Shank.

Ling: You’re a new playwright—and, let me tell you, considering this is your first play, it’s fantastic—so I’m curious: what was the process of playwriting like for you?

It was a lesson in learning how to write. I would write, consult craft books, try to fix the problems, write again, go back to craft books, and over and over again. I have written many, many versions of this play as I learned the elements of story. I think I’ve read most of the classic playwriting books! I often found myself coming up against problems I didn’t know how to solve, and then along would come the answer in the form of a book or video or comment someone would make. I also loved Lauren Gunderson’s playwriting YouTube sessions: they were such a light in some of the early, dark months of the pandemic.

Locally, I was very fortunate to find a playwriting group, Lincoln’s Playwrights Collective, where I learned so much from critiques of my scenes and those of the other playwrights, too. It was the Collective’s parent organization, Angels Theatre Company, that arranged the first full readings and critiques of the script, and then eventually decided to produce the play along with the sponsoring presenter, the Lied Center for Performing Arts.

Does that sound like a tortuous and long experience? It was! From start to the world premiere, it will have been about six years.

Ling: Were you able to find any similarities between playwriting and your “day job,” as it were?

Shank: Absolutely. I definitely put my research skills to use as I learned not only about Bonhoeffer, but also his world: economics, politics, theology, sociology. I read many, many scholarly articles as well as popular books. Even though my “day job” writing was as far from creative writing as is possible, I certainly was able to apply my persistence in believing I could convey complicated information in a way that made sense to the audience. Academic and policy pieces can get pretty battered by criticism, but that process has helped me separate who I am from what I write and that enables me to better accept and use critique, though I’m not saying it is always easy.

Ling: What inspires you as a playwright and an artist (because you’re most certainly an artist now!)?

People who are willing to sacrifice inspire me. Sacrifice requires that revenge or self-preservation be conquered by courage and love. Strangely, the older I get, the less I understand self-sacrifice. It seems to me now, more than ever, the willingness to put self aside for another person or for a greater good requires the highest selflessness. And, in the case of Bonhoeffer, it required his willingness to allow his reputation to be ruined and, ultimately, the loss of his life.

Ling: Though the play’s title is clearly pulled from a religious quotation, how did you settle on that one?

Shank: It’s a line from a hymn, A Mighty Fortress is Our God, written by Martin Luther. The hymn was one of Bonhoeffer’s favorites, though he felt it was often sung too slowly. He preferred a bouncy tempo. I thought verse four captured Bonhoeffer’s life:

That Word above all earthly powers

no thanks to them abideth;

the Spirit and the gifts are ours

through him who with us sideth.

Let goods and kindred go,

this mortal life also;

the body they may kill:

God’s truth abideth still;

his kingdom is forever!

Ling: I’ve been on both sides of the table in the past, so I’m curious to hear: what has been your experience, thus far, working with a full artistic team? Has anything surprised you? Has anything been particularly beneficial, or, on the other hand, odd?

Shank: It has been an incredible experience. I keep finding myself at a loss for words when I am with these spectacularly creative people who are pouring their talents into the production. But I’ll try to articulate something for you! I would say that it has been almost disorienting. The script that has lived in my head for so many years is now out in the world and new things are being created based upon it. The cast are bringing the characters to life with their own wonderful insights. The costume designer is enhancing the emotion with choices in clothing colors and styles. The sound designer is bringing amazing aural impact to the production. It’s incredible, really.

From the other side of the proscenium, I never realized the level of intricacy and unified teamwork theatre requires. Because the play is premiering in the community where I live and because the director, Timothy Scholl, is very collaborative, I am learning so much about how theatre is made. I’ve been asking lots of questions and everyone has been incredibly kind. It’s magic.

Ling: I know some of my favorite facts I’ve discovered, but to you, as a Bonhoeffer enthusiast and resident playwright, what is your favorite thing you’ve discovered while writing this play?

Shank: The entire Bonhoeffer family loved–and I mean loved–the performing arts. It’s entertaining to read Bonhoeffer’s critiques of performances he’s seen. The family took the performing arts very seriously and had the same high expectations for the arts that they had for themselves as a family, and I’ll tell you, the family had very, very high expectations for its members. Most of the family played at least one musical instrument, and they held regularly scheduled music nights where they would sing and play. Bonhoeffer was so talented as a pianist that it was thought he might become a professional. But when a famous musician friend deemed Dietrich would only be good enough to be one of Germany’s best pianists, and not one of the world’s best pianists, it was decided that Dietrich would need to find another career. Dietrich loved music his entire life. I tried to reflect this in the play.

Ling: Do you have any other artistic endeavors lined up for the future? Would you return to playwriting again?

Shank: When it comes to playwriting, I have caught the bug. I feel like I’ve learned a lot and there’s so much more I want to learn. I’ve written a monologue and have a couple longer scripts I’ve outlined and am working on.

On a more long-term basis, I am at work on a novel. I’ve finished the first draft, and, if playwriting is any indication of my process, it means it will go through many drafts before it is completed!

For me, writing is a long-term process, and it is hard to know when it is done and whether your work will ever see the light of day. A fun contrast to that has been the book-focused podcast my sister, Linda Culbertson, and I started. It’s called the Front Porch Book Club (https://frontporchbookclub.com). Every month we choose a book. The first episode, she and I discuss it, and the second episode, we invite the author or some expert on to discuss the book with us. That short turnaround with two finished products every month has been very satisfying!

This Mortal Life Also plays at the Lied Center for Performing Arts (Lincoln, NE) March 17 – 20, 2022. For more information, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.