In 2013-14, an innovative, cross-disciplinary research project explored the interactions of translation and adaptation, theory and practice, academia and ‘industry,’ in the sharing of plays from all periods with contemporary audiences. Presented here by editor, researcher and translator Emma Cole, a new and diverse volume of essays brings the issues explored in this forum to readers, expanding them further and inviting others to join the conversation.

We are regularly exposed to theatre that starts its life in another language, whether this be in the form of an ancient play newly adapted or a brand new, politically-sensitive drama quickly translated to make its debut in English. Yet the various processes involved in transforming a play from one language to another and in producing the final text are often cloaked in mystery, with a translator’s work sometimes hidden under a subsequent adaptor’s name and the existence of a published script downplaying the complexity of the negotiations and decisions involved along the way. These processes are far more than just linguistic, but involve contemplating the place of a text within a theatre’s culture, balancing explanatory alterations with the ethics of such interventions, and perhaps even choosing between prioritising the author’s text as written or the effect of the original text on audience experience. Every theatre translator makes hidden choices regarding these questions constantly throughout every single translation, many of which are repeated when a director or group of performers subsequently translates the drama from page to stage. The ambiguity surrounding the practice is furthered through the lack of formal training schemes geared towards theatre translation, and the façade of a traditional separation between the theory and practice of translation, the domain of academics and artists respectively.

A 2013-14 project held in collaboration with University College London and the Gate Theatre, Notting Hill titled the Theatre Translation Forum sought to remove some of this mystique and to bring together all those invested in the area to discuss issues surrounding writing and staging translated drama. These seminars ultimately led to the volume Adapting Translation for the Stage, which was published this month and seeks to bring the discussions held at UCL out to the wider public, and to break down the barriers between theatre translation theory and practice, artists and academics, ‘literal’ and ‘performable’ translation, and even adaptation and translation. Artistic Directors from the United Kingdom and the United States, directors, translators, playwrights who adapt ‘literal’ translations, academics, and individuals who move between several of these labels share their experiences and allow for the similarities and differences between theatre translation in a range of fields and countries to be more readily understood and appreciated.

The original Forum explored theatre translation within four distinct fields: naturalism, ancient drama, modernism, and contemporary drama, with last category referring to the translation of plays by living or very recently deceased writers. Each theme was explored within a seminar and an associated practical workshop. The seminars brought together academics in university language departments, classics, and theatre departments, alongside a translator currently working on a project intersecting with the relevant theme. A director, translator, and group of actors ran the associated workshops, which consisted of open rehearsals and group discussions regarding the practicalities of moving translated text onto the stage. Participants from universities including UCL, Oxford, Queens University Belfast, and companies such as the Gate Theatre, Scarlet Theatre, and the Royal Court contributed to the events, making the project a truly interdisciplinary and interprofessional event.

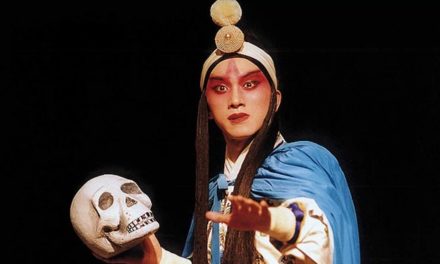

The Theatre Translation Forum’s Naturalism workshop at the Gate Theatre, London, October 2013 .

As is often the case with exploratory work the Forum asked more questions than it answered, raising debates about the specificity of practice within the United Kingdom and drawing attention to the blurred roles of those working at the intersection of theory and practice, such as academics working as professors in university language departments whilst simultaneously authoring critically-acclaimed translations for the stage. When Geraldine Brodie (the initiator of the Forum and my co-convenor) and I considered the prospect of publication we consequently sought to broaden the project’s scope, eventually deciding to combine a curated selection of papers from the original Forum with newly commissioned pieces from Australia, the United States, and Continental Europe. The final volume is structured via the four original themes, with an individual who crosses the theory/practice divide opening each section, setting its agenda, offering a precis regarding the current state of play, and surveying future directions of the field. The chapters themselves bring directors, academics, artistic directors, translators, and adaptors into dialogue, with transcribed discussions, co-authored chapters, and solo investigations into translation practice shining light onto this long-hidden field.

The volume’s central aim is to provide theoretical advances into theatre translation. The title, for example, condenses two traditionally polemic terms within this field—translation and adaptation—and in doing so suggests that they can coexist on stage in mutual collaboration. The introduction proposes that rather than think of translation and adaptation as an either/or dichotomy, they instead be thought of as a spectrum, or continuum, forever in flux and embodying the potential to loop back on itself. Conceiving of practice in this more fluid way facilities the employment of more precise markers regarding an individual’s work, several of which are offered within the volume. Tom Littler, for example, explores the idea of ‘total translation’ in his direction of Howard Brenton’s versions of Strindberg’s plays, while William Gregory and Marta Niccolai reconsider the terminology surrounding the domestication/foreignization debates as relating to the translation of Latin American new writing and Dario Fo’s political theatre respectively.

My own contribution explores a new concept of translation through the work of Sarah Kane. Kane did not work as a translator, and indeed little is known about her foreign language proficiency. Yet one of her five texts for the theatre was a reworking of Seneca’s Phaedra, and her two professional directing credits both relate to theatre translation, with her own production of Phaedra’s Love opening at the Gate Theatre in 1996, and a production of Büchner’s Woyzeck following at the same theatre in 1997. Given that Kane’s work also frequently appears in translation around the globe, particularly within Germany, the way it intersects with theatre translation is worthy of more careful attention. I focus purely upon Phaedra’s Love, which Kane was at pains to remove from its classical sources in interviews about her work, famously claiming that before writing she only looked at Seneca once, and never read Euripides or Racine. Although this may the case, I suggest that a close and complex relationship between Kane’s play and the legacy of Seneca’s tragedy exists, and that this relationship can usefully be thought of in terms of translation theory. I posit that Kane’s script embodies the idea of paralinguistic translation, and involves Kane translating linguistic tics, such as the idea of a burning love, alongside themes, dramaturgical strategies, and the history of Senecan tragedy within Jacobean revenge tragedy and the twentieth-century avant-garde to create a complex, nuanced drama richly imbued in theatre history. I suggest that it is only by attending to the traces of linguistic and paralinguistic translation in Phaedra’s Love that we can more fully grasp what the play can achieve, and that the concept of paralinguistic translation might provide a useful lens of analysis for other reworkings of classic texts that have a non-normative linguistic kinship.

Adapting Translation for the Stage is filled with new insights key to anyone working in theatre translation or interested in watching translated drama and intrigued by the processes that go on prior to the realisation of the finished product. We hope that the combination of so many different voices, from different fields and with different ways of working will change the way that theatre translation is conceptualized and understood, and that the sharing and adopting of practice that started in the Forum might now percolate out into the wider translation community. And this is just the beginning. The volume concludes with an externally-facing afterword by Eva Espasa, which examines the practicalities surrounding translation training, and how translation theory relates to accessibility questions over surtitles, audio descriptions, and sign language. These dimensions are offered as key questions for future debate, and should to be coupled with more international investigations not only of translation into English but out of English, and stretching further afield than Europe and the Americas. But for now, the conversation has begun, and we’d love for you to listen and join in.

Emma Cole is a Teaching Fellow in Liberal Arts at the Department of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Bristol

Readers of The Theatre Times can purchase the volume with 20 per cent discount using the code FLR40 at this link.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emma Cole.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.