Light is elusive, mercurial, and ephemeral. It remains invisible to the eye until it collides with an object, revealing what it strikes while concealing what it does not. How to talk about something as ambiguous as light has been the problem of the Lighting Designer since the dawn of their craft; in fact, most find the craft itself almost impossible to describe. In his essay The Painter, Cory Pattak uses allegory as a way to share the experience of what it is like to be a Lighting Designer.

Imagine you are a painter and you have just been commissioned to create a new painting. The criteria for your painting is fairly specific. The subject, background, tone, and desired emotional impact are laid out to you. The people that have hired you to create the painting are not painters themselves but are avid art fans so they explain to you, as best as they can, their vision for this new piece. Sometimes they try and describe techniques that they have seen used in other paintings; other times they simply talk in the abstract. They give you a timeline for when you may begin working and a deadline for when the painting must be completed. They ask you what supplies you enjoy working with–what kind of brushes, canvas, paints–and they provide you with a small stipend with which you may acquire these tools. You spend countless hours thinking about the painting you are about to create; what colors you might use, what strokes you might make, what new techniques you might try. You sketch out some ideas on the back of a cocktail napkin that minutes ago held an onion tartlet, but you may not begin painting until the given start date. You continue to discuss with your employers what their painting will look like. They’ve already cleared out a spot on their wall for it and you hope that it will be something they are proud to display in their home.

The Audience, Directed by Lou Jacob, Set Design by Anne Mundell, Costume Design by Wade Laboissonniere, Lighting Design by Cory Pattak, Maltz Jupiter Theatre, 2016.

At last the big day arrives, the day you will start painting. You wake with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. Your employers have secured you a place to work but when you arrive you discover that you will not be painting in your own quiet solitude; a small group of people has gathered to watch you work. Among them are some of your closest friends, some with whom you hope to become friends and others who might possibly one day commission you to create a work of art for them. You have great respect for many of these people. One or two are excellent artists themselves–perhaps a sculptor, maybe a glass blower. A giant countdown clock is started, and you begin painting. Every color you choose, every stroke you make, every involuntary flick of the wrist that dabs a droplet of paint where you never intended, is witnessed by the onlookers. Although the painting has just started to take shape your employers offer thoughts and suggestions based on what they’ve seen so far. Sometimes you overhear them discussing the painting with other people in the studio. The beads of sweat trickle down your face while the clock, wish as you might, never stops.

Cory at the Tech Table, photo by Marcos Santana.

In the lower left-hand corner of the painting, you create a beautiful rendering of a duckling. It was only on a whim that you decided to place her in your painting but now that she exists, you can’t help but fall in love with the crook of her head, her perfect shade of yellow, the spot of dirt on her left foot. Your employers tap you on the shoulder and say that while the duckling is lovely, there should not be a duckling in the corner, but instead a gazebo in the center of the painting. Other people in the room share their agreement. The duckling is beautiful, but she has to go. You say goodbye to her. As quickly as she was born, she disappears behind a patch of grass made by your unforgiving brush. Maybe she’ll find her way into a future painting. You begin the gazebo. You don’t spend too much time on it because the clock is still ticking away. You trust your instincts, you follow your gut, you draw on the experiences of every other painting you’ve ever done, and you try to make this one the best.

Cory Writing Light Cues, photo by Ethan Steimel.

Thankfully, you get to take a break and so you step away from the canvas. You don’t want to be rude to everyone else in the room so you chat with them. Some of them compliment you on how the painting is coming along, others offer advice. You step out in the foyer to call a gallery curator about his upcoming commission. Although he knows you’re currently working on a new painting across town, he very much would like to discuss his new painting. He asks you when you can get together to discuss ideas, and what brushes you might want, and what new inspirations you’ve recently had. You promise you will get back to him soon but now you must go complete the gazebo.

After weeks of work, the clock has nearly run out. There is so much you’d still like to paint, but when the clock hits zero, it’s brushes down. Just as you’re finishing painting the belt buckle on the redheaded girl’s Sunday dress, the clock chimes. Time is up. You gather your brushes and wipe your hands clean. The doors to the studio burst open and hundreds of people file in to see what you’ve created. “The paint is still drying,” you warn them, as you force a smile. “How are you feeling about the work?” one of them asks. You mumble something polite but your head is still spinning. You suddenly remember that you forgot to paint handles on the stable doors. Oh well…hopefully no one will notice but you. Your employers are thrilled. They already have an idea for another painting they’d like to discuss with you. You thank them for the opportunity and promise to call them soon to hear about their new idea. You grab an onion tartlet on your way out and avoid making direct eye contact with anyone. You eventually make it out onto the street.

The cold air hits your face like a wave crashing ashore. You take a deep breath. You think of her…the duckling. But they were right, she had to go. Perhaps another time…Your phone buzzes. Your email beeps. A colleague bumps into you. You make some small talk. There are paintings you’ve agreed to paint all over the city, all over the country. Some will be large murals, others just an unassuming still life. Canvases of all shapes and sizes painted with brushes that were only created yesterday, and others that have existed for decades. Some of the paintings are just a kernel of an idea while others are taking shape. In one studio, a blank canvas is sitting on an easel waiting to feel the tickle of your brush covered in azure paint. That touch will come when you make the first stroke, tomorrow morning, in front of a whole new group of spectators. You allow yourself a moment of sheer panic, the acknowledgment of the utter lunacy of it all. The painting you just created, labored over, was just a visitor–momentary, ephemeral. This time next month, that painting will only exist in the memory of those who saw it with their own eyes. There will be no more painting. It will be put out with the trash and a new painting will quickly take its place. Did it ever exist at all? You know the answer. You gave it life. You witnessed its birth. You can’t help but smile. How could anyone choose to do this? You breathe in the cool air and start walking. You must, because another canvas awaits.

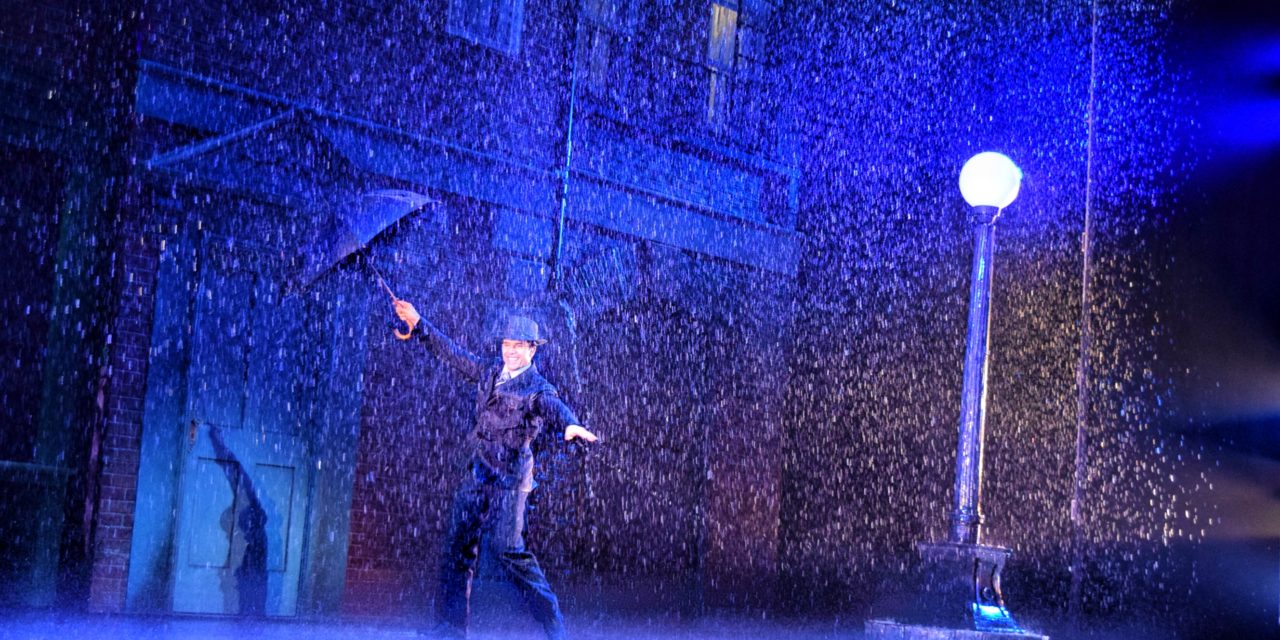

Now, what if the paint wasn’t paint, but light?

Me and My Girl, Directed by James Brennan, Set Design by Paul Tate DePoo III, Costume Design by Gail Baldoni, Lighting Design by Cory Pattak, Maltz Jupiter Theatre, 2016

Cory Pattak is a Lighting Designer whose Off-Broadway credits include Stalking The Bogeyman, Revolution In The Elbow…, Handle With Care, Daddy Long Legs, Skippyjon Jones, This Side Of Paradise, Unlocked, Nymph Errant, With Glee, and The Blue Flower. His Regional Theater credits include shows at The Old Globe, Goodspeed Musicals, The Kennedy Center, Maltz Jupiter Theatre, Weston Playhouse, Everyman Theatre, Syracuse Stage, and Cap Rep. Cory was nominated for a 2018 Helen Hayes Award for his work on In The Heights at The Olney Theatre. He is host and creator of “in 1: the podcast” featuring interviews with theatrical designers. www.corypattak.com

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Cory Pattak.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.