The 10th MITEM Theatre Festival continues to showcase the theatre achievements of Hungarian national theatre and productions from other countries. Almost every evening on the stage of the Hungarian National Theatre, whose building resembles an ark of salvation, a variety of world languages are heard and the audience watches theatre productions from the world repertoire. Different genres, schools, acting techniques, director’s decisions, but invariably vivid impressions. One of the guests of the festival was The Overcoat by Griboyedov State Academic Russian Drama Theatre from Tbilisi. The performance, labeled by director Avtandil Varsimashvili as an “Absurd Tale in One Act” involved the audience in the atmosphere of a frenetic and catchy balaganza. No one, however, suffered except for the text of the source material and its semantic background – Nikolai Gogol’s short story of the same name.

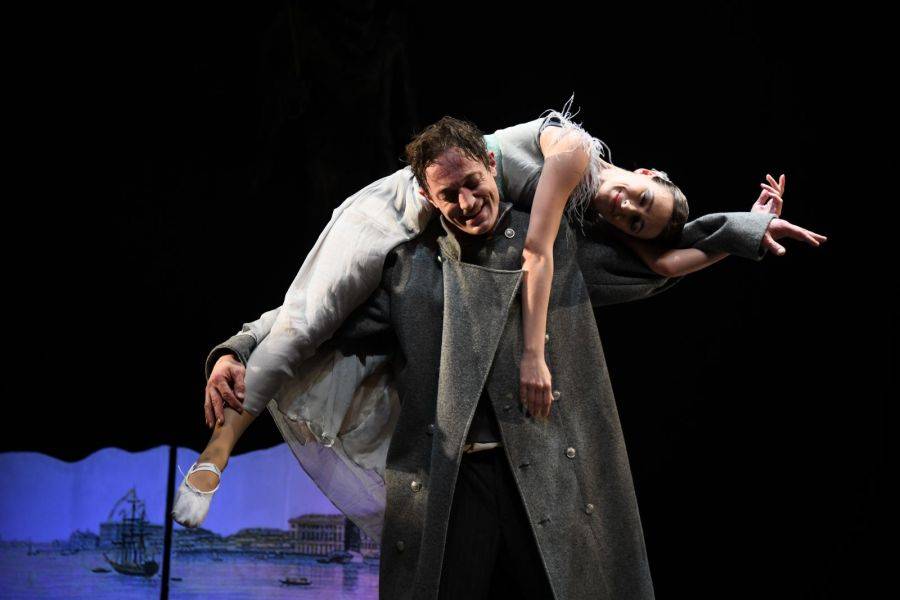

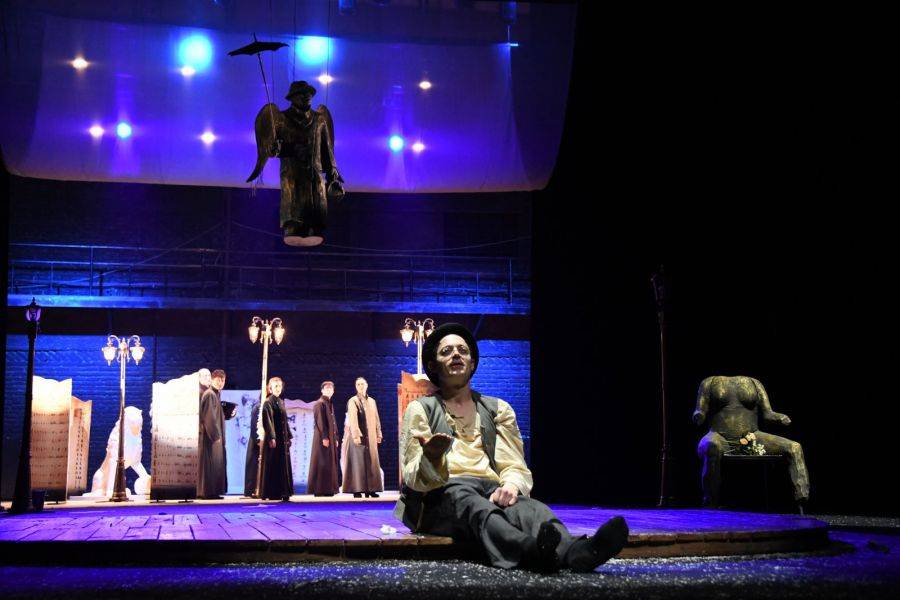

As is often the case when staging prose, the director latched on to one of the phrases in the story in which a character’s impressions of an overcoat are compared to a woman. The director subordinated the production to this central concept – the overcoat is a woman – and then lavished it with jokes, quips, divertissements and gags. The result was a rude balaganza with skomorokhs and a sense of Gogol’s famous Sorochinsky Fair, but not of St. Petersburg’s Nevsky Prospect. Gogol’s text turned out to be “overplayed” and defeated by a pile-up of theatrical “kunststück” not of the first freshness, and it is a pity that those who have not read Nikolai Gogol’s brilliant text will get acquainted with it for the first time in such a simplified, straightened version, devoid of halftones. The genre of phantasmagoria, extravaganza or comedy of the absurd, which this production – which has been touring since 2019 – is presented with at various festivals, is flexible and seems to tolerate everything. The Overcoat’s production seeks to entertain, to excite, to catch attention, in short, to use all the techniques of catchy fairground or street theatre, and that would be all right if the production were not based on such an important, subtle, complex work that desperately resists such an interpretation.

Gogol’s Overcoat is a hagiographical story of a little man who lived, in the strict bureaucratic hierarchy of St. Petersburg, enslaved and depersonalized. Regulations, diligence, and obedience to the charter replaced personality in him. A clerk in the department, writing out letter by letter every day in neat, diligent handwriting, he failed to write the story of his own life. The most striking and fatal thing in his existence was the purchase of an overcoat to replace an old overcoat worn out to an indecent state. A joy that did not last long, for the overcoat was stolen. This plot, born from an anecdote, became one of the cornerstones of Russian literature. The famous phrase “We all came out from under Gogol’s Overcoat” is a quote most often misattributed to Dostoevsky. Nothing comes out of The Overcoat, staged by Avtandil Varsimashvili, except laughter from that part of the audience that is not aware of the original source and a feeling of awkwardness among those who more often know The Overcoat from their school curriculum.

Photo courtesy of the 10th Madách International Theater Meeting.

The production of The Overcoat was made in the same way as the overcoat was made in Gogol’s story: cheap and cheerful, with a simple invention and with the festival in mind. The goal has been achieved – the play successfully tours and wins local awards, and one can only praise the professionalism of the director, who managed to “marry” a great work of Russian and world literature with superficial theater. But it’s a damn shame that the spirit of the time, the feeling of the era, as well as the satire and sharpness of writing inherent in Nikolai Gogol, have completely disappeared from the performance of the Georgian theatre, performed in Russian in front of a European audience based on the work of an author who is desperately divided between Russia and Ukraine.

The Overcoat is a text about how the system kills the human in a person, without them ever noticing. The Overcoat is a text about mercy and humanism, which cannot be completely killed even in people who have become functions. The Overcoat is a text about the bitter frost, about the piercing cold of the empire, faceless forms, laws, and rules, about the soul-freezing world order, in which everyone is looking for their own way to warm up. Maybe a booth organized by the artists is also a way to warm up the audience. The artists create a convincing ensemble, they technically execute all the mise-en-scène and the director’s ideas, and it seems they could solve an absolutely beloved work of the world classic in such a manner. Travesting serious fragments that hurt the soul, they seem to reconcile the viewer with the harshest reality. A kind of theatre therapy. Only the moral message of The Overcoat is about something completely different. Where Gogol has the tragedy of a little man against the backdrop of the tragedy of an empire, Avtandil Varsimashvili has the ethereal suffering of a worthless supposedly creative person who failed to protect his creation, his woman, his overcoat. The character of this Overcoat is pitiful, but you don’t feel sorry for him, just as you don’t feel sorry for the hero of a sitcom slipping on a banana peel, the comedian is in pain, but there is laughter in the audience. If Gogol’s Bashmachkin is weak and unresponsive, then this stage Bashmachkin seems not timid, but lazy, lethargic and inactive. Maybe this is how the director sees the current sons of the century, unable to protect what is most precious? An alarming diagnosis, which, however, has nothing to do with the performance, designed to entertain, and not sow seeds of sadness and doubt in souls.

Photo courtesy of the 10th Madách International Theater Meeting.

The theatre of the absurd, stated in the subtitle of the performance, is expressed only in the rough seams of the scenes, sewn in as if for laughs. But absurdity always has logic. This is all the more important considering that Bashmachkin, who turned into a ghost, according to the plot, is in a sense the forerunner of Franz Kafka’s Gregor Samsa from The Metamorphosis according to Vladimir Nabokov. All these thoughtful considerations, however, have nothing to do with the performance, which, starting from one of the phrases of the story, simply pushed away its foundation and launched into a cheerful round dance, carrying the viewer along with it. The viewer does not know that this is dancing on the bones of the immortal hero Nikolai Gogol.

And yet, The Overcoat in the MITEM program seems appropriate, given its multicultural component and being a kind of respite between other dramatic performances of the festival, full of a high degree of relevance, directorial searches and thematic layers. This is the characteristic and distinctive feature of the MITEM festival – it is a unity of dissimilarities, uniting different types of theatre, genres, schools, themes and directions. Each performance here is remarkable in its own way and evokes vivid emotions, and there is no indifference, indifference or formal attitude to what the viewer is invited to see on stage. There is a place for buffoons and high passions here.

Photo courtesy of the 10th Madách International Theater Meeting.

Avtandil Varsimashvili’s Overcoat is a Gogol-lite performance. It’s probably good for school trips or for when people come to the theatre to be entertained. It neatly avoids sharp Gogolian corners, and translates satirical passages of the text into wicked jokes and playful sketches. But this Overcoat is not capable of warming thought, it has no philosophical lining. It is a light summer windbreaker. But such things are also necessary in the “theatre wardrobe”.

In its time (a time – different from the current feverish period) this version of The Overcoat successfully toured both in Ukraine and Russia and won awards at some festivals. Maybe then the performance had a different look, different dominants. But today the Overcoat acquires a special sound and dramatism, which is ignored in this performance. If in the children’s play about Gulliver’s adventures recently shown at the MITEM festival, the adult audience caught the subtexts and semi-tones, then in this Overcoat, made for an adult audience, on the contrary, there is an attempt to use primitivism to highlight what is happening. Buffoonery does not lend itself to wise, subtle and precise words and it seems that in rare moments of silence Gogol’s story addresses the troupe of the play in the words of its protagonist – “Leave me alone! Why do you insult me?”.

Photo courtesy of the 10th Madách International Theater Meeting.

Photo from the official website of MITEM festival

https://mitem.hu/en/programme/performances/the-overcoat

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.