The relationship between theatre and life has been pervaded the work of dramatists from Shakespeare to Maria Irene Fornes. The porosity of the relationship, the boundaries and fissures of the interaction permeate plays as diverse as Fefu and Her Friends, Noises Off and The Dresser. Àlex Rigola may have turned to some of the key works of the naturalist stage in his reworking of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler (2022 ) and Enemy of the People (2018) – but both productions have been marked by a rupturing of the fourth wall that asks probing questions of the relationship between actor, character and audience. Rigola’s work in increasingly compact, empty spaces where the actors’ bodies create the décor with minimal props and costumes point to an aesthetics of economy. It is as if the actors have stepped out from the audience or the front of house staff, boundaries broken down in a prising apart of actor and role. This relationship reaches a new dimension as the former director of Barcelona’s Teatre Lliure, Madrid’s Teatros del Canal, and the Venice Theatre Biennale opens his own theatre, Heartbreak Hotel, on Olivereta Square in the working-class Badal area of the city.

Rigola has dispensed with the wooden box that he created to house the audience-actor encounters of his nomadic theatre company Heartbreak Hotel but its legacy remains. The 72-seat theatre, sharing the company’s name, also evokes something of the mood of other fringe theatres like the Sala Flyhard and the original Teatre Lliure in Gràcia — indeed the architects responsible the Lliure’s renovation in 2010, Francesc Guàrdia and F. Xavier Massagué, also designed Heartbreak Hotel. Unlike the Lliure, however, here the stage is a narrow entity where the actors and audience have a minimal distance between them. The actors talk to the audience with a sense of intimacy, almost in whispers and the mood is that of a rehearsal. We see every gesture and movement as if in close up; the actors too see the audience – every move, every shift, even the soft sound of pen on paper of this reviewer appeared to echo through the space.

Rigola’s work in promoting a poetics of proximity between stage and spectator has been seen as the key characteristic of much of his work of late, including Who is Me. Pasolini (2016) and Vania (2017). For the opening of Heartbreak Hotel, Rigola takes Thomas Bernhard’s 1984 play Der Theatermacher and reworks it as L’home de teatre – translated as a The Man of Theatre as a fitting showcase for Andreu Benito – too long a figure associated with supporting roles on the Catalan stage. Benito has had key roles in Pau Miro’s Eva contra Eva (2020) and Dostoevski’s Orgull (2022) and here he demonstrates the versatility and craft that have made him such an outstanding performer, playing an ageing actor-manager lamenting the direction in which the theatre is going. Theatre has been a family business for him with his wife and children part of the company, but the cantankerous, melancholic actor is finding it hard to let his son Àlex (Àlex Fons) take over the ropes, finding fault with his every gesture and suggestion. His wife and daughter, like the theatre’s technicians, is absent. One of the production’s strengths is the way in which the production conjures a plethora of characters who are mentioned, referred to but never seen. Only Andreu, Àlex and front of house manager Marwan (Marwan Sabri) appear on stage but the community needed to make work and ensure the show goes on are repeatedly evoked.

The show begins with a crisis relating to the emergency lighting. Andreu wants Marwan, the Front of House Manager, to allow the fire officer to turn off the emergency lighting for the opening. But like Godot, he waits for an entity that will not turn up. From this premise, a discussion of theatre’s role and purpose emerges as Andreu laments the decadent state of contemporary theatre and the lamentable position he now finds himself in – having once toured the country’s most opulent theatres, like the Lliure and the Catalan National Theatre, he is now stuck with a second rate venue – the Heartbreak Hotel – Bernhard’s play takes place in an inn where the actor Bruscon and his company are due to play. Rigola has condensed Bernat Puigtobella’s earlier translation and transposes it to a Catalan context where Andreu’s new production is in the final stages of rehearsal. Bernhard’s rant against Austrian mediocrity is here inflected to a Catalan context where Andreu’s play about historical “heroes” — Churchill, Napoleon, and Rafael Casanova, defender of Barcelona against Bourbon troops in 1714 — also features guest appearances by two self-styled “heroes” with far reaching implications for Catalonia’s current identity: Spain’s dictator Francisco Franco – who ruled between 1939 until his death in 1975 and Jordi Pujol, the powerful head of the nationalist party Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya party from 1974 to 2003 and President of the Generalitat Catalan government from 1980 to 2023. Both make guest appearances in Andreu’s play that testify to their toxic roles in shaping both Catalonia and Spain’s sense of self. Àlex brings a portrait of a young Franco in full military uniform on stage confusing him with Pujol. A country forgets its history at its peril; Andreu is haunted by the ghosts of a past he can’t shake off; he laments the local businesses closing down and looks back with a degree of nostalgia to an era that might only have existed in his imagination. Àlex wants to forge a future where he determines the past. Neither appears able to deal with the complexities of the present.

Heartbreak Hotel’s auditorium is a black box that harks back to the Théâtre Libre of André Antoine – black seats, a black floor, a black brick wall and a door to the dressing rooms stage left. Stage right a wooden wall – a nod perhaps to the wooden box that provided him with such a productive space for Hedda. Four strips of white lights above the actors on the low stage ceiling beam down on the black floor. I am struck by the silence in the theatre as the piece begins: Marwan Sabri as Front of House Manager coming on stage to ask us to switch off our phones: no vibrations, no silent button. Off. Fully. Rigola worked with acoustic engineer Oriol Arau on the venue and the results are spectacular: this is an eerie silence, surreal in its purity. The auditorium conjures the sense of a space sealed off from the white noise of the world outside. To call Heartbreak Hotel an empty space, however, feels disingenuous; the ghosts of its former role as a mechanics workshop – a place of making and doing — hover over the venue. There is no bar here – in that it resembles Madrid’s austere Teatro de la Abadía where Rigola’s production of Lorca’s The Public played in 2015. Lorca’s play shares with Bernhard’s a view of theatre as increasingly decadent and irrelevant, unaware of its purpose and role; this is a theatre that needs shaking up. Andreu directs Àlex – clad in a red cape with ruffles and there is something of An Actor Prepares in the reflections on the process of formulating a role. He barks out orders and provides firm instructions but Àlex can never be Andreu – the latter refers to his son as “my great deception”. All actors play characters they are not; the absurdity of a famous actor playing a king is not lost on Andreu. In this respect, I can’t think of a better production to share with students as a way of reflecting on who gets to make work and why, what positionality means and how plays engage with the histories and lives they chronicle. L’Home de Teatre is a piece about theatre and it is in Marwan Sabri’s Front of House Manager that the pragmatics of a different future might lie. His openness offers another way forward – a third way in what Andreu terms “a comedy that is really a tragedy”.

Elvis Presley’s 1956 hit “Heartbreak Hotel” was allegedly inspired by the suicide of a man who jumped out of a hotel window. Heartbreak is perhaps a condition both of life and of theatre – from The Oresteia to The Inheritance. Heartbreak is core to who we are and how we learn to navigate life. How we harness it and hold it is perhaps one of the reasons of being for theatre. “Hearbreak Hotel,” Rigola tells me, “Theater as a healing space. It breaks our hearts. This is a good place to heal them.” Indeed, Àlex Rigola provides a venue to do just that. Go and spend 65 minutes in the company of Andreu Benito, Àlex Fons and Marwan Sabri. I’m so glad I did.

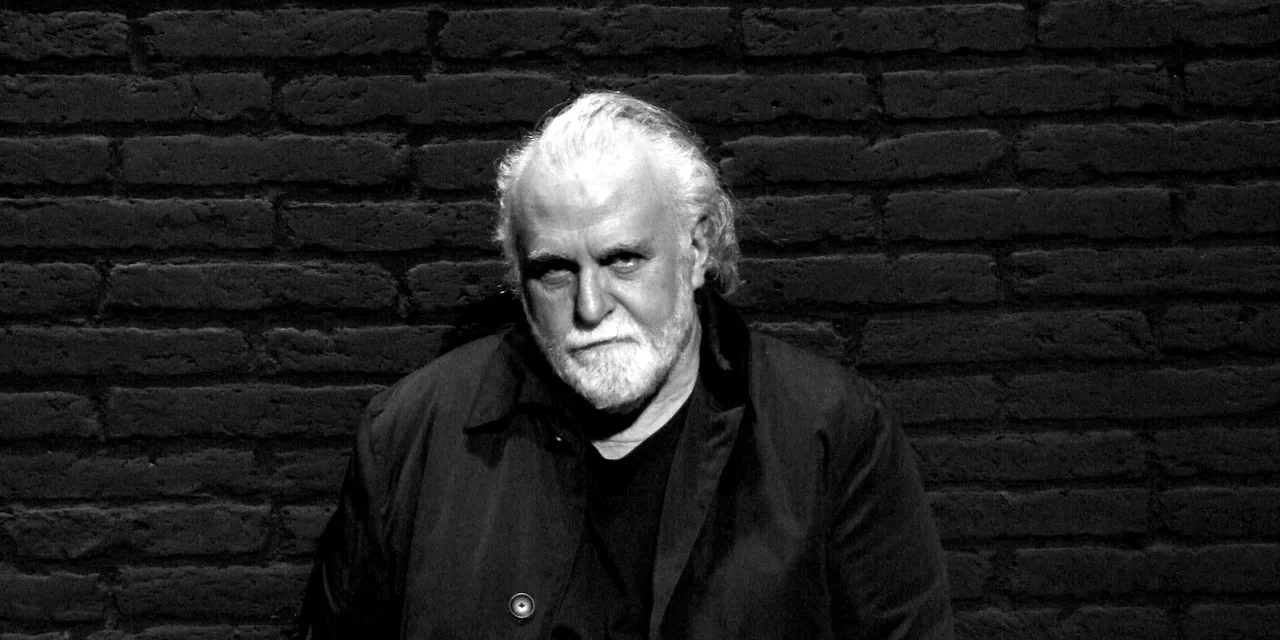

Heartbreak House Teatre. Photo: Maria Delgado

L’Home de Teatre plays at the Heartbreak Hotel Theatre until 21 January 2024

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.