Since 2015, over one million refugees have entered Germany. As a political event, the so-called refugee crisis continues to color public policy and political rhetoric in Germany and around the world. ![]()

Less well-known, however, is Germany’s artistic response to this crisis, especially on the stage.

Germany has a long history of political theater. But the influx of refugees since 2015 – what some have called the greatest humanitarian catastrophe of our era – has created new challenges for depicting crisis on stage, from striking the right balance between political activism and artistic creation, to figuring out the best way to reflect events as they unfold.

The result has been a German theater scene that has doubled as a platform for political action – one that blurs the lines between social work, radical activism and art.

Political ‘Theaterkultur’

In their response to the refugee crisis, German artists are working within a unique tradition of political “Theaterkultur” (theater culture).

It has its roots in the 18th and early 19th centuries, when dramas by authors such as Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Friedrich Schiller and Georg Büchner addressed contemporary debates about national identity, social inequality and revolution in their works.

Today, this political orientation is further advanced by Germany’s public funding of theaters. In contrast to the United States’ more limited public arts funding model, the German government provides generous financial support at the national and state level to some 140 theaters. This frees those institutions from a high level of dependency on ticket sales and private donors to cover expenses. In turn, many German directors have more freedom than their American counterparts to experiment, provoke and cover controversial political topics without having to pander to current trends or audience expectations.

In the 20th century, Bertolt Brecht added to this tradition. His radical artistic agenda viewed theater not as entertainment but as an instructive experience aimed at spurring its audience on to social reflection and political action. For instance, his 1939 work Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (“Mother Courage and her Children”) harshly criticized countries that sought to benefit financially from World War II.

Against today’s politically charged artistic backdrop, the German theatrical response to the refugee crisis has been swift and profound. In 2015 alone, the theater website nachtkritik.de published a partial list of performances or events at over 75 individual theaters that directly engaged with the refugee crisis. And two years later, a glance through the calendars of Germany’s theaters, both large and small, shows that dialogues about immigration and asylum are still taking place on the stage.

Depicting crisis

But how, at the level of performance, do German theaters grapple with an issue as complex as the refugee crisis? In other words, what does a humanitarian catastrophe look like on stage?

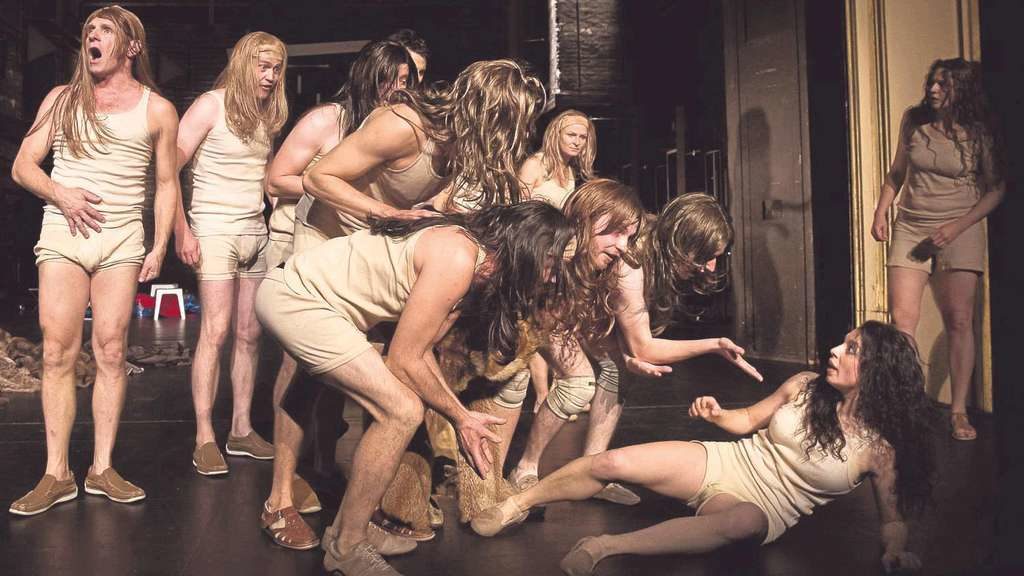

The most overt way theaters have tackled these issues is through performing new works that directly confront the crisis. Perhaps the most iconic of these is Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Schutzbefohlenen (“Charges”), an extended dialogue between refugees and Europeans.

Although the piece was first published on her website in 2013, Jelinek expanded it four times between September 2015 and April 2016 to reflect contemporary events, such as the hundreds of refugees who died while crossing the Mediterranean. Since 2015, it has been performed hundreds of times in Germany and has been celebrated as a “text of the hour.” The piece is a hard-hitting cry for recognition and dignity, and heavily criticizes what Jelinek saw as the hypocrisy of European humanists who turn a blind eye to the suffering of refugees within their own borders.

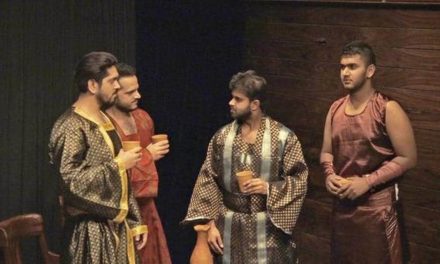

Another way of bringing the refugee crisis to the stage is through the politically charged reinterpretation of canonical works. Here, a central drama has been Lessing’s 1779 work Nathan der Weise (“Nathan the Wise”). Set in 12th-century Jerusalem, it describes how a Jewish merchant named Nathan, a Christian knight and the Sultan Saladin successfully bridge the gap between their three religions and cultures.

Contemporary directors have preserved the piece’s plea for respect and tolerance, while updating the setting to reflect contemporary politics. Director Dominique Schnitzer, for instance, set the piece in a refugee camp in a production opening in January 2017 in Osnabrück. He left off Lessing’s happy ending, leaving reconciliation in question.

Cornelia Kempers (Daja), and Ronald Funke (Nathan) in Lessing’s Nathan der Weise. Directed by Dominique Schnitzer. Photo: Marek Kruszewski

Art meets activism

Many theaters have taken their engagement a step further, reshaping themselves into spaces of political action.

Since 2015, theaters have collected thousands of dollars in donations to aid those affected by the crisis. Some, like Berlin’s Maxim Gorki Theater, have offered to help refugees fill out visa or work permit applications. Others, like the Schauspielhaus in Hamburg, opened their doors to refugees in need, offering emergency housing. Still, others have taken action aimed at raising awareness among German citizens, such as the Schauspielhaus in Bochum, which shut willing audience members in an 18-wheeler to commemorate the 71 refugees found dead in a truck in Austria in 2015.

After 71 dead refugees were found in an abandoned refrigeration truck in September 2015, the Bochum Theater organized a public reenactment of the tragedy. Photo: Ina Fassbender/Reuters

Neither the performances nor the political actions have been free of controversy.

Theaters have been accused of promoting Gruseltourisms (“horror tourism”) – the idea that privileged audiences are simply experiencing the horror of the refugee crisis as entertainment. Others have criticized German audiences who “do penance” for their lack of real political involvement by spending their Friday evenings in the comfortable seats of the local theater instead of getting involved in their own communities.

In the end, though, even these controversies can facilitate discussion about how to appropriately respond to an event as devastating as the refugee crisis.

Low ticket prices and a deeply ingrained Theaterkultur mean that German theater reaches a wider and more diverse audience than in America. Even small German villages have their own theater scene, and altogether theaters attract around 35 million visitors each year – three times as many as the country’s First Federal Soccer League.

This wide reach, accompanied by the willingness to make politics visible on stage, allows German theaters to provide a vital space for dialogue about one of the most pressing issues in contemporary Europe.

Emily Goodling is Ph.D. candidate in German Studies, Stanford University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emily Goodling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.