There is something beguiling, provocative and timely in Andrés Lima’s staging of Antonio San Juan’s new play Asesinato y adolescencia / Assassination and Adolescence. What San Juan and Lima do to expert effect is to bring together two terms, concepts and ideas that might not easily rest side by side because here death is linked to adolescence in ways that suggest a social fear of coming of age, of the liminal space between childhood and adulthood. The deaths that are chronicled by the news items projected on screen and attributed to a serial killer — tellingly named el monstruo (The monster) — preying on teenage and pre-teenage girls, speak of a society at once mourning the potential that these girls represent and fearing the liminality of what adolescence and its state of transition signals.

Lima’s habitual collaborator Beatriz San Juan provides an empty stage where only a pliable metallic wall of three panels protrudes. This serves as a plain backdrop for the action as well as a screen providing projections of the news items documenting the deaths of teenage girls. The live and the virtual intersect as teenage Lucía (a raw Lucía Juárez) rebels violently against a world that doesn’t understand her. She’s angry with her mother, her school, and her life. Only her younger sister Rosita – alluded to but never seen – is spared her wrath. Lucía has little time for school and school – judging by the tale of a maths teacher that wonders what she is doing in the classroom – appears to have little time for her. Lucía defies easy stereotypes. She is studying at the Lycée Français, part of a middle-class family that doesn’t appear to have overt problems but dysfunction takes many forms and Lucía is rebelling – screaming at her mother, setting fire to her bedroom, self-harming, and seeking solace in drugs and alcohol.

The audience first see her sitting on the floor, centre stage, drinking what appears to be a bottle of spirits — she laughs, drinks and then drinks more and more until she flops like a rag doll. A song plays in the background that speaks of extremes: satisfaction here involves devouring someone whole. Lucía wants to hang out with her friends but is all too often alone. Her friends are tellingly seen only on screen. And while she searches for them and calls them from her phone – the phone conceived as an extension of her hand and her sole companion – they rarely answer.

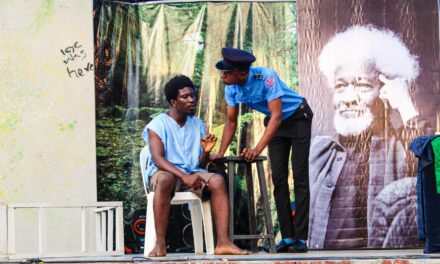

A serial killer is on the loose and it looks as if it could be Luis, a guard at a young offenders’ institution who watches Lucía and other teenagers hanging out in the local park. He may be the killer but then again perhaps the audience want him to be the killer. As played by Jesús Barranco, he is a lean, willowy figure, who might have stepped out of a Tim Burton film. With his shaved head, dark raincoat and black trilby hat, he feels more part of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) or German expressionist film of the 1920s – indeed Lima and San Juan have cited Fritz Lang’s M (1931) as a point of reference. Lucía tells Luis that he looks as if he has come from an old film “your face like the tip of a walking stick.” The close ups projected of his face on the screen point to Nosferatu but also a vision of criminality that expects serial killers to look “evil”. He falls against the wall and the surface folds around him as he shrivels to a heap. The serial killer murdering the teenage girls is known as the monster; might this middle-aged man who doesn’t appear to fit in at work and has no discernible friends be this monster?

Lima’s production creates an aura of fear around every corner. Juárez’s skinny Lucía cuts herself in panic, fear and anger – with a giant teddy wrapped around her in ways that remind the audience that she is still a child. Luis watches Lucía from around the screen; he creeps up on her, silently opening the hidden door to appear when least expected. Barranco also takes on the roles of chat show participants who each occupy entrenched positions on the “youth problem” — shifting his seat to deliver each’s opinion. Both participants are unwilling or unable to listen to each other. At the end, they blend into one, indistinguishable in their intransigence. Can we be surprised that our young people are in such pain when the adults they see in the media are so angry and inflexible?

Footage of security guards in a children’s home munching their lunch while Luis looks on distantly point to Luis as an outsider. Luis is largely silent, his voice measured and quiet while Lucía screeches and screams until she is practically hoarse – but like Luis she is an outsider. Both are isolated in the live space from the onscreen characters who exclude them. The filmed interviews with teenagers reflecting on attempted suicide, eating disorders, addictions, and frustrations provide a context for Lucía’s narrative – she is one of the many rather than a sole figure, even though she does not realise it as she wanders drunkenly across the stage, screaming and ranting. One teenager reflects on screen that “I didn’t want help.” Another that “I wanted to stop feeling and thinking.” But feeling and thinking is exactly what this work invites of his audience. The reporters may speak of children as the future, but the murders show their expendability. Saying and doing are two very separate things in this production.

Lima and San Juan have conceived a piece embedded in research with those in the know: former members of child gangs, child psychologists, lawyers with expertise in this area, and crucially, the teenagers whose views are projected on the screen. The piece was constructed through workshops with teenagers and their voices are very present. There is no attempt to provide answers, simply a space to let teenagers tell their story on screen and, in Lucía Juárez’s performance, live. Violence is never far from the surface, always threatening to erupt fuelled by alcohol, cigarettes and drugs. Lucía trembles with cold as she solicits a cigarette from Barranco. She is seen shivering as she prepares to smoke heroin, meticulously preparing the concoction. Alcohol and drugs dull the senses and provide both fuel and comfort, but the relief is all too temporary for the shaking and screaming begins again all too soon.

Miquel Àngel Raió’s video design is as in-yer-face as Juárez’s performance and as sinewy as Barranco’s moves. Valentín Álvarez’s lighting creates pockets of action on the stage while Beatriz San Juan’s design – a screen, a wall and a shield — with its hidden door both exposes and masks the two protagonists. Nick Powell’s music captures the volatile climate, merging pop, electronic sounds and the pulsating rhythms that echo in Lucía’s head. C. Tangana’s song “Comerte entera” (Eating you whole) opens the piece, as Lucía drinks and laughs hysterically; it reappears through the show sung and hummed by the two actors – a song about extremes, all or nothing, that might serve as Lucía’s leitmotif. Luis’s extraordinary scissor dance in an apron – knife in hand – as he tells of entertaining a group of teenagers at home has an edge of danger and hysteria that links him further to Lucía. She may think that he represents protection, but his antics show an edgy side. The fact that he may be the monster that is murdering the teenagers further reinforces the ominous dimensions of the scene. Nothing feels innocent with Luis. As he crumples to the floor, supported by the back screen, the sounds of an omelette being whipped up for dinner as Manolo Caracol is heard on the radio accompany text projections on the screen that explain that Luis is making his supper: three different registers (the sonic, the live body and the projections) all working to destabilise who or what Luis is or might represent.

What distinguishes Assassination and Adolescence is its refusal to judge. It presents an on-stage world where representation (through film, media and the digital) shapes who its protagonists are and how they position themselves. When media coverage feels irresponsible, is it perhaps any surprise that Lucía is so disdainful of what it represents. Violence surrounds Lucía: news items revolve around murder; footage is screened of a young man being beaten by security guards at the children’s hone where he resides. Murderers must be presented in the press as monsters and demonised. But teenagers are also demonised as a social danger. The characterisation of Luis seems to suggest that the monster lies within – often able to move unnoticed because of a capacity to not draw attention to themselves. Luis operates in the shadows. He may know which of the children in the park are in the children’s home he polices, but they fail to notice him. How capable, the production seems to be asking, are we of seeing what lies in front of us – whether it is disturbed teenagers or serial killers? And why are we so quick to judge? This intelligent, visceral production eschews social realism in its heightened performance register. Rooted in two outstanding performances, it invites its audience to reflect, without ever preaching or opting for the obvious, on a society where violence is all too pervasive.

Asesinato y adolescencia / Assassination and Adolescence runs at the Sala Max Aub, Naves Español en Matadero until 5 November.

Expressionism prevails: Jesús Barranco as Luis in Asesinato y adolescencia / Assassination and Adolescence. Photo: Esmeralda Martín, courtesy of Teatro Español

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.