“This,” the Chicago Tribune critic reminds us on the billboard of seemingly every tram stop in Melbourne, “is why we go to the theatre.” Before killjoy wags respond–“to see a stage version of a film version of a book series popular 15 years ago?”–it is worth knowing the genealogy of Harry Potter And The Cursed Child, the theatrical spectacular that has opened at Marriner’s Princess Theatre and could run until the next millennium.

That genealogy may not be noble, but it is old. It has little to do with wizards and spells per se, though these have made solid appearances over the centuries. It is not a genre or a stage style. Nor is it culturally-specific, since it can be found in the pasts of many nations. It exists as a phenomenon in its own right.

It is, of course, The Big Show, and before its stentorian rhetoric (“the most awarded production of the Broadway season”) and promises of visual superfluity (“the sets, the scene changes, the costume, actual magic”) rational thinking bends its knee, and die-hard Potter fans stow dissatisfaction with its narrative presumptions (“Harry as an adult?”).

Theatre has its reason that reason does not know. When it pulls out all its scenic, choreographic, and performative stops, who can resist, even at up to $175 a ticket?

The Australian company of Harry Potter And The Cursed Child. Photo Credit: Matt Murphy

Ancient Rome and all that

The writer Apuleius described a scene from The Judgement Of Paris, staged in the first century CE:

There was a hill of wood, similar to that famous mountain which the poet Homer called Ida. It was fashioned as a lofty structure, planted with foliage and live trees, from the highest peak of which a flowing stream ran from an artificial fountain. A few goats grazed upon the grass. Then…through a concealed pipe, there burst on high saffron mixed with wine which, falling in a perfumed rain upon the goats, changed their white hair to a fairer shade of yellow. And with the entire theatre sweetly scented, an opening in the ground swallowed up the wooden hill.

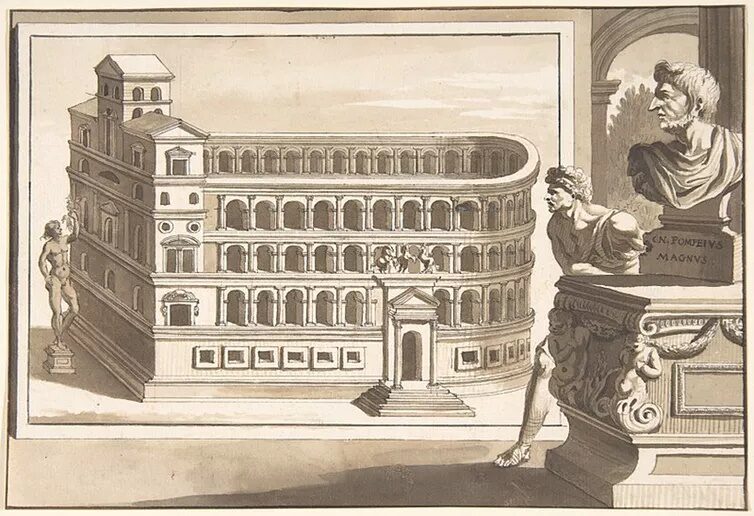

The ancient Romans did not invent The Big Show, but they brought it into purpose-built venues. The Theatre of Pompey (55 BCE), one of the first, had an auditorium 500 feet in diameter and seats for 18,000 people.

Productions used crane-like mechane, thunder boxes, rope systems, trapdoors, and complicated pegma, or flying machines. (One unfortunate actor came loose from his harness during an enactment of the Icarus myth, and hit the floor so close to Nero he splattered the Emperor’s clothes with blood).

Jan Goeree: A Reconstruction of the Theatre of Pompey (before 1704). Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Greek tragedy with its speechifying family dramas (The Oresteia) and worthy plays about the refugee crisis (The Trojan Woman) could not compete, and faded from the repertoire. The bitter struggle between The Small Show and The Big Show has been going on ever since.

Masque costume Wikimedia Commons

Over the last 2000 years, the latter has taken many and impressive forms. There were Medieval mystery plays, with their beautifully decorated maisons and whole towns given over to extravagant recreations of bible stories, and Jacobean Court masques, with intricate designs by the architect Inigo Jones; eye-popping, 18th-century perspective scenery, with families like the Bibiennas dedicated to painting extravagant Baroque trompe l’oeil; and the actor-managers of the 19th century who, as the theatre ticked into a new fascination with realism, cast children dressed as adults and placed them at the back of vast stages to heighten the audience’s sense of distance.

The 20th century saw more than its fair share of epic theatrical spectacle. One proponent was Austrian director Max Reinhart. His extravaganza, The Miracle, was presented in London in 1911 before a pole-axed audience of 30,000, with a multi-national cast of principals, and 1,800 extras. Glen Byam Shaw who played the part of a cripple miraculously cured described its monumentality:

I was brought in on a stretcher, supposedly completely paralyzed, and laid out on the front of the main stage. The priest started chanting prayers, and this was taken up by the whole cast, number 250 people. It grew louder and louder. At a certain point I started to move my arms very slowly, and then to drag myself off the stretcher and crawl along the floor…I reached the steps leading to the niche where the Madonna was standing. I struggled up them…gave an agonized cry, and was restored to health…Then the whole crowd cheered, and the orchestra and choir burst out into a hymn of praise.

Big Show, Big Risk

Such productions are obviously costly. For most of their existence they have been possible only through imperial, Church or royal patronage. Patronage is still a factor–think of the millions governments pump into Olympic Games ceremonies today–but in the last 200 years commercial theatre has claimed The Big Show for its own. Ticket sales have replaced treasury gold, and market considerations have edged out political ones.

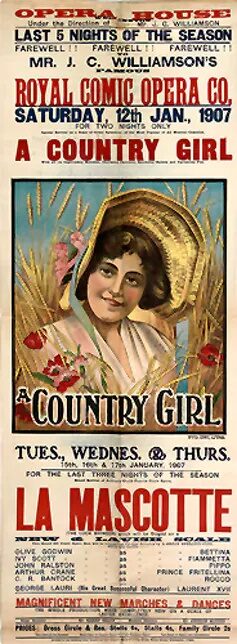

Print for a 1907 J.C. Williamson production of A Country Girl. Wikimedia Commons

In Australia, the entrepreneurial genius of J.C. Williamson fashioned a vast conveyor belt transferring theatrical product from Britain to Australia for the purposes of having fun and making money (or making money from having fun). The key, as with Harry Potter And The Cursed Child, was franchising.

In the 1880s, Williamson bought the license to perform Gilbert and Sullivan operettas in Australasia, and his fortune was made. But in theatre, as in cake baking, luck doesn’t last forever. By 1975, the Williamson empire was on its last legs, and it looked to be over for commercial theatre in Australia.

Instead, taxpayer subsided companies became the major purveyors of professional live performance, later joined by a sprouting of international arts festivals. The Big Show survived the transition, though in an art-ified way, absorbed into a different style of programming.

The Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Nicholas Nickleby in 1984 is sometimes considered to be the moment when state theatres, previously dedicated to classics, George Bernard Shaw, and the odd Australian play, took a Big Show turn.

Since then The Big Show has hovered uneasily between a rump commercial sector (Harry Miller, Michael Edgley, Gordon Frost, etc.) and state company seasons, especially the STC and MTC, who have pockets long enough to compete in the major musicals market. Broad appeal productions have become increasingly important in an era of declining government subsidy, so commercial and non-commercial theatre have drifted closer in sensibility and offerings as a consequence.

Depending on your view this is a step towards accessibility or a rank betrayal of art. One thing is certain: Big Shows impose big strains on budgets, and when they tank, they leave holes in which Small Shows disappear.

And beyond the financial issues, lie aesthetic considerations. As this brief history suggests, The Big Show’s strength is meeting expectations, not subverting them, while its proclivities are the visual and spectacular, not the verbal and intellectual.

It has its place, but its dominance in the marketplace can be oppressive. Williamson’s empire ruled Australian theatre for nearly 100 years. It was not an especially impressive reign.

Harry Potter And The Cursed Child, however, is the brainchild of overseas producers and occupies a dedicated commercial theatre venue in the Princess (one of Williamson’s, built in 1886, with a retractable roof, currently unused, alas. It is unlikely to complete with small-scale interpretive dance productions on global warming, or outdoor revivals of Attic tragedy.

It will be amazing, and incredible, and have stage effects in it that people will talk about for years and years. Until the next Big Show, in fact.

And that will be the real magic.![]()

This article appeared in The Conversation on February 26, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Julian Meyrick.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.