Germany has more theatres and concert halls than almost any other country in the world. From its many small, private theatres to the large opera houses, stage designers are always working to ensure a special theatre-going experience.

Germany applied to UNESCO for intangible cultural heritage status, citing the highest concentration of theatres in the world. And in the small cellar theatres and large concert halls, for all the plays, puppet theatres, operas and musicals: stage designers are always working behind the scenes to ensure audiences enjoy a special experience at every venue. In an interview, set designers Katrin Nottrodt and Philipp Fürhofer provide insight into the world of stage design in Germany – and tell us what they find particularly fascinating about their work.

Nadine Berghausen: Ms. Nottrodt, Mr. Fürhofer, both of you have worked for many years at different venues at home and abroad. Do you feel Germany has a unique stage design tradition; is there such a thing as typical German stage design in a sense?

Philipp Fürhofer: There have been countless prominent stage designers in the history of German theatre – from architect Friedrich Schinkel and Austrian Josef Hoffmann, who designed the set for the first performance of Richard Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung in Bayreuth, to Bertolt Brecht’s legendary stage designer Caspar Neher, to name just a few, very different examples. This diversity of content and aesthetic in sets continues to grow to this day. Even in a city known for its theatre scene, like Berlin, I can easily recognize the individual styles of the respective directing teams, but I can’t identify any overriding characteristics or any that could be seen as exclusive to Germany. What I can say with confidence is that the extraordinarily large number of theatres and stages in Germany has encouraged a tradition of diversity.

Katrin Nottrodt: The theatre world is very close-knit in Germany and we all exchange ideas. This also creates competition, and we all keep a positive eye on what our fellow designers are doing. This adds an element of fusion that immensely enriches the world of culture.

NB: You describe a scene characterized by diversity and exchange where very different styles are featured on stage. Is this unique to Germany or is it more a peculiarity of the art of stage design?

Philipp Fürhofer: Like almost every other area of society, art, and theatre in particular, is a space where very different kinds of people meet, most of them Europeans who also tend to work in an international network. Stage design is always part of the complete work of art created by many participants. It evolves from dialogue among directors, actors, and the large theatre team. So it makes sense that this collaborative process results in great diversity, and here Germany is no different from other European nations with a rich cultural scene. Additionally, many theatre professionals like myself are not just involved in productions in their homelands, but also abroad.

NB: Where would you place stage design in relation to disciplines such as architecture, and the visual and performing arts?

Katrin Nottrodt: Stage design is an amalgamation of all three. By the time my work, the stage design, goes on exhibit, I have read and interpreted the text it is based on, talked to the directors, taken criticism on board, drafted plans, constructed three-dimensional models, made technical drawings, calculated a budget, worked with craftspeople in workshops on building all the elements and created lighting moods. In stage design, the artist has to be willing to reject his or her own ideas and accept those of others in the artistic team.

Philipp Fürhofer: The history of stage design is full of pioneers and rebels. Architects and artists like Friedrich Schinkel, Bob Wilson, Pablo Picasso, and William Kentridge all worked more or less frequently and intensively on stage designs. I personally work as a visual artist in various multimedia fields, and stage and costume design is one form of art that has fascinated me since I was a child.

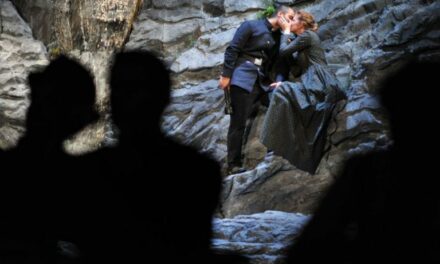

Staging of Peer Gynt after Henrik Ibsen at the National Opera Norway in Oslo. Stage design: Katrin Nottrodt. Image: Erik Berg.

NB: How important is stage design in the theatre world?

Katrin Nottrodt: Unfortunately, stage design is not always given the respect it deserves. The time frame for completing a design has gotten shorter and shorter, seasons are spontaneously rescheduled and we are hardly given enough time to explore the subject matter and come up with ideas. To play devil’s advocate: If critics don’t mention the stage design, then it didn’t bother them. It is even worse for costume and lighting designers, who are often not mentioned at all. There are the awards given out by theatre magazine Theater heute that we would all like to win, of course. And the Bund der Szenografen (Association of Stage Designers) continues to represent our interests better and better. While this is very important, it would still be nice to have more appreciation and attention.

NB: What do you love about your work despite the challenges?

Philipp Fürhofer: I am always aware that a good evening at the theatre is only possible when all the parts work together. The stage design is a very direct and immediate factor that accompanies the audience throughout the performance from the moment the curtains open. This aspect fascinates me. Actors, lines, and sounds come and go; the stage set ties it all together throughout the performance.

NB: You were both invited to Denmark for the German-Danish Cultural Friendship Year 2020. Mr. Fürhofer, you have already realized two opera projects there and are now working on a production of Hamlet for the Holstebro Theatre. Ms. Nottrodt, you designed Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen. What has your experience in Denmark been like so far? Have you noticed any differences between working at a German and a Danish theatre?

Philipp Fürhofer: My experience here has always been excellent. The Danish are polite, friendly, and professional. There are differences in the work and production processes, but they are not typically German or typically Danish and instead depend on the respective theatre. I’m sure it’s completely different working in Copenhagen than in Aarhus, but the State Opera in Munich and the Schaubühne in Berlin are just as different.

Katrin Nottrodt: I also believe that we all see ourselves as independent artists, and in this respect, Germany is no different from Denmark. In this sense, we are all the same.

This article was originally posted at goethe.de in April 2020 and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nadine Berghausen.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.