Olga Voronkova is a London-based, Belarusian video editor, scriptwriter, copywriter, and producer working with Belarus Free Theatre and Young Vic. Her work focuses on the intersection of acting and theatre with social activism, psychology, and human behavior. Her most recent project for the European Theatre Convention – as part of Young Europe IV – shares stories of Ukrainian refugees for school-age audiences in London. Young Europe IV is a 3-year programme focused on young audiences and the non-dominant voices in our societies and their stories. Young Europe IV is the winner of a 50,000 EUR prize and the Art Explora – Académie des Beaux-Arts European Award 2022.

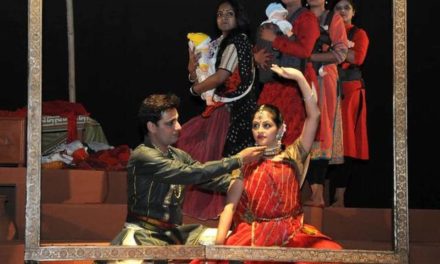

Work produced by Olya Voronkova. “Kupalle”, director Svetlana Efimava

Kasia Lech: Can you explain your journey to the project and what interests you in this project?

Olga Voronkova: I represent Belarus Free Theatre (BFT) in the project which is a quite unique organisation. All its members – actors and people involved in production – come from different, diverse backgrounds, most of them are activists and volunteers. It is expected that the members try all the roles in theatre, that they are flexible and can take on different job at any time.

I was quite involved in Fortinbras studio, an educational division of BFT, back when I lived in Belarus. It was my second full-time job at the time, and I studied acting, playwriting, directing, and producing plays right in the field. I participated in creation of performances, as an actor and a creative asset.

Then, I moved to London in 2014, and my cooperation with BFT stopped. I’ve been keeping in touch with everyone, but didn’t take part in any theatrical activities, as I started working as a video editor here. However, there has long been an idea, supported by Nicolai Khalezin, the dramaturg and co-founder of BFT, that it would be good if I wrote something for the theatre. I had done some writing before, but I would never write the whole play. In 2021, one of theatre managers found out about Young Theatre IV project and got involved in it. Nicolai offered me to participate on behalf of BFT. Besides, there has always been plans to work more with young people. The theatre is actually staging a play with teenagers at this moment in Warsaw.

KL: Is Belarus Free Theatre collaborating with any Warsaw theatres?

OV: Not that I’m aware of. Recently, they finished work on a performance with Ukrainian and Belarusian teenage refugees. It is called “Пасля дзяiнства” (Post-childhood). I know that сhildren have had workshops and acting training. Then, they started to develop a play about their personal experiences. It worked well and resulted in a new performance. You can see it in a Free Belarus museum in Warsaw. Maybe in other locations, it is worth to check. As I said, BFT is interested in working with young people and performing for young audience, so Young Europe IV is a great opportunity for us.

Once I discovered about the project in November 2021, I immediately started to think about the theme for the development. The first idea coming to my mind was an immigration experience. I live in London and half of London’s population comes from other countries. I definitely represent his part, but I wanted to avoid place naming and was going to set the story in another time and in meta verse, which was the centre of tech discussion at the time. Transferring familiar issues to a whole new dimension seemed like an exciting challenge.

Then the war in Ukraine broke, and it affected me a lot. At that time I couldn’t imagine I could write about anything else. My thoughts were entirely preoccupied with that tribulation. So, I started to develop a new idea in February 2022, although the launch of the project was in May. By that time, I met Ukrainian refuges here in London, had zoom interviews and online questioning with Ukrainian teenagers who left for other countries. I collected lots of similar and yet different stories of witnessing a sudden end of peaceful life and being forced to flee. The setting of my play is London because that’s where I met refuges from Ukraine in person and where I had my personal experience as an immigrant.

KL: That is really interesting. Will you be writing about Ukrainian experiences or Belarusian experiences?

Work produced by Olya Voronkova. “Seagull”, director Maria Sazonava.

OV: I write about Ukrainian experiences. I met many Ukrainians, and those people moved me. I also could relate to their frustration of finding themselves in another country. At the same time, I realise that being forced to leave one’s home and become displaced is a completely different experience than choosing to move voluntarily. It is a whole new level of trauma, which I was willing to explore.

KL: The project is about others and obviously, people from East of Europe as a whole have been othered. We’ve been silenced while someone else speaks about us. But how do you approach that? Obviously, it’s a different relationship between Belarus and Ukraine, there’s a commonality of suffering, but again it is one speaking for the other. This debate has been happening in Poland. Are we entitled as Polish scholars to write about Ukrainian theatre, or do we make sure that Ukraine speaks for Ukraine? How do you manage that, when it’s someone else speaking for Ukraine about Ukrainian experiences?

OV: When I was deciding on the subject, I was so struck by the situation in Ukraine that I couldn’t imagine writing about anything else. Later, I began to have my reservations on whether I was allowed to write it, and I discussed my concerns with my writing mentors. Now it is sad when I think about it. I acknowledge that Ukrainians are the best people to tell their own stories, but is it wrong for me to write about something that feels so important to me? I did a research and created a plot all based on interviews and true events. Along the writing it also became clear that the main theme of my play is loneliness. Experiencing isolation and misunderstanding is universal and relatable to anyone. Besides, I cannot go back to my country due to the risk of being detained for my political views, so despite the absence of a war there, I know the feeling of not being able or fearing to go home. I know the worry for the homeland and loved ones there. Feeling like an alien in a new country. I am sure many Ukrainian artists write about this now, and their voices are definitely more important, then mine. We will see and hear more of their art as time goes by. However I’ve made a choice to use an opportunity to tell their story to young people in London. One could ask, why adult playwrights speak for teenagers and their experiences. Another reservation on my mind.

Student’s play in studio “Fortinbras”, director Dzyanis Tarasenka.

KL: You said it’s based on interviews, so are they talking to someone? Are these monologues or are they talking to each other? I don’t know how much you want to reveal as well, so it’s up to you.

OV: Yeah, they’re talking to each other, sharing their experience. It’s a combination of different stories, it’s not just one, but all of them happened. They’re talking to each other, but it’s not verbatim.

KL: So, it’s based on the interviews, but it’s your dramaturgical imagination.

OV: Yes, exactly.

KL: Interesting, and what language do they talk to each other in?

OV: English.

KL: Why?

OV: Well, I made the first draft in Russian, then I translated it to English to share with writing mentors on the project. Later I edited the draft in English. I tried to write new parts in Russian and then translate to English, but found it too complicated, switching back and forth. Because it’s going to be staged here, in local classrooms for local audience, it feels it should be in English. Children in classrooms may have different background, speaking many languages, apart from English, so I had to choose a universal tool to tell the story. Which is English language in this country. And that’s another challenge, deciding on what English it should be.

KL: This is such a big question, especially in this interview when both of us negotiate ourselves and our thoughts in English we do not speak. One is always looking in one’s head, negotiating syntax…

OV: It is a great challenge as I mentioned. It is stressful for me, but fairly exciting as well. If I were to tell the plot of my play in English, while speaking if front of you now (irony alert), I’m not sure I could convey the message or even get you interested, because of the language barrier, enforced by personal trait of being socially awkward in the situations like interviews. Writing is rather different form of communication though. If I were to check and amend my answers later, I would have time to think on the best way to explain my thoughts.

So I hope that the time I have for the writing, along with the technology and editor’s assistance on my side, will help me to tackle a language barrier. I’m also very grateful to have mentors on the project, who share valuable comments and support my writing journey. When I write in English, it is still a translation in a sense of adapting my thought and my character’s voices to this particular tool of expression. It takes a lot of time to think of each phrase, I won’t hide, but I also enjoy it.

KL: What English are they speaking?

OV: I chose for my play a clear, grammatically correct language. It’s not going to belong to any subculture, but it will be rather informal and easy. It is the English people in the world learn at schools at their language lessons.

Work produced by Olya Voronkova. “Kupalle”, director Svetlana Efimava.

KL: So then what is the message you want the play to send to audiences?

OV: First of all, it is a story of coping with loneliness, caused by trauma. In my play, I’m showing… how people find different strategies to cope with it. For example, displaced children experience their trauma mostly through their parents. Parents are usually most worried and anxious, while children are not responsible for dealing with typical challenges that refugees face. They deal with a sudden change a lot, but sorting out the accommodation, income, food, and future is typically the task of their adults, usually their mothers in the case of Ukrainians. This experience can be a tremendous stress for any adult, and not many people can fully bear it with resilience. Sometimes children unconsciously take on their parents’ emotional burdens. Many factors play a part here, including the way parents cope, so, the experience is quite different from family to family.

KL: What’s the difficulty of being a playwright with language as your tool, but the native language is then taken away? The difficulty of being a playwright with your tools taken away from you?

OV: It’s a big challenge. It would be much easier for me to write in my native language. Here, I have to focus on things that can be understood by everyone. The tools may be taken away from me, but feelings, personal relationships, all the elements of life are not. So, I focus on people, the message, and the stories and emotions that everyone can understand. My tool is just basic human expressions, manifestations, and traits.

KL: Why talk about Eastern Europe, Ukraine, and migrants in particular, within a project that looks at marginalized voices? Why is that important?

OV: Living in the UK, I often find myself of two minds. On the one hand, I am fully aware of local agendas and worries, but on the other hand, I also have an understanding of what matters to people in some countries of Eastern Europe. I see that there can be a tremendous gap between these perspectives.

Perhaps it is a constant experience for immigrants to feel a sense of longing to belong. While I choose to embrace this new world fully and learn its ways, I also hope that this world will make an effort to understand my perspective on different matters. I am not sure if this is a utopian idea, but the urge to explain and share my perspective is always there, no matter how much I try to blend in. Something is screaming from inside of me: “You need to understand me! I want to show you how to look at the problem in another way! It is important to me, so it also can be important to you!”

Actually, is it important to me, if others understand me? More accurately, I would say that I want to be seen.

So I would like to bring my perspective on immigration to people from Europe, from the UK. Because it’s not the only island in the world.

~

Young Europe IV runs from 2021-2024 and is hosted by the European Theatre Convention. The project focuses specifically on non-dominant stories and ‘forgotten’ voices in our societies. The classroom plays are currently being performed at participating theatres and will be performed at a festival in 2024.

To read more about Olga’s work and the other playwrights involved with the European Theatre Convention, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Allison Newey and Kasia Lech.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.