A magazine editor friend of mine expressed a similar sentiment:

“The entertainment industry is notoriously ruthless, a social jungle ruled by an even harsher version of ‘survival of the fittest,'” she said. “But this show tells us that we have another chance, that we can feel alive again, and that’s inspiring.”

When the show’s producers landed on the concept of Sisters, I’m sure they had women like my friend in mind as potential viewers. The show’s advertising deliberately used positive, stereotype-smashing language calculated to highlight the charisma, bravery, and confidence of its mature stars. To quote one of its taglines: “Thirty ‘sisters’ defy age, convention, and labels to form a band.”

Although certainly politically correct, that’s probably going too far. “Sisters” is ultimately just another idol show. What it delivers — and what keeps viewers hooked — isn’t empowerment, but vicarious thrills.

At first glance, Sisters does seem unconventional. Most idol shows feature contestants in their teens and 20s. “Semi-finished goods,” these aspiring stars are more than willing to play by the rules and ingratiate themselves to the show’s almighty judges.

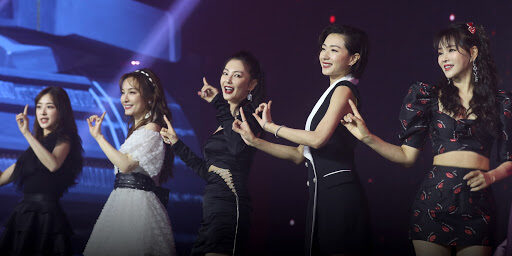

Annie Yi, 52, performs during Sisters Who Make Waves From @伊能静 on Weibo.

The industry veterans of Sisters, on the other hand, flout the rules, challenge the program’s crew, and push back against the judges. When an on-camera director asked Taiwanese singer Annie Yi — at 52, the oldest contestant on the show — to cover her knees, she wasn’t having it. “Can’t we do it my way for once?” she asked. “Just let me sit here in peace.”

It’s a gratifying scene for the audience, who gets to experience the excitement of watching the show’s power dynamics momentarily flip. The show likely also benefitted from audience disgust with the omnipresent “data economy,” in which young stars with fanatical Generation Z fan bases like Cai Xukun monopolize the public discourse. Indeed, one of the biggest celebrity dust-ups of the past year took place when disgruntled Generation X and Millennial backers of mandopop star, Jay Chou, briefly toppled Cai from his place atop the microblogging platform, Weibo’s, hot topic rankings. Sisters, too, is a reminder the world doesn’t always revolve around ingénues or their “little fresh meat” counterparts.

Yet for all the praise Sisters has received for its premise, the show’s primary conflict isn’t between women of a certain age and the stereotypes holding them back, but between two very different subgroups of female celebrities. The 30 women in Sisters may all be of roughly similar ages, but they come from extremely disparate backgrounds.

The first group, which exudes self-confidence — some might say conceit — have years of show business experience, successful careers, and, in some cases, the financial support of male benefactors. Kitty Zhang, for example, is known both for her still-sharp acting skills and her tendency to put on airs. Fellow actress, Eva Huang, is less acclaimed, but enjoys the backing of her producer husband. They joined Sisters not because they needed the gig, but for the novelty of being in a female band. And viewers revel in watching them break the rules, defy the judges, and provoke the producers.

The second group has more to lose. Some were once showbiz darlings who have since found themselves relegated to low-end publicly funded performances; a few have been all but forgotten. Compared with the first group, they come off as much meeker. But that doesn’t mean they’re not willing to do whatever it takes to win: Sisters might be their last chance to revive their careers.

This dynamic is not unique to Sisters. At its core, the show, like all idol shows, is a competition between those who have something to lose and those who don’t. The conflict between them is grounded in their disparate resources and connections. The country’s premier idol competition, “Produce 101,” also tends to pit girls who are born rich and who want to be famous against those who stand to gain everything by winning.

A still from the online series Sisters Who Make Waves 2020. From Douban

Despite its “girl power” trappings, Sisters has also come under fire from a number of Chinese feminists. One commentator argued that, while the show ostensibly emphasizes a diversity of female values and female beauty, its stars are still primarily appraised, consumed, and favored for their attractive appearances, svelte figures, dewy skin, unrealistic pep, and extreme self-discipline.

Even though I agree Sisters doesn’t live up to its feminist branding, that’s taking things a little too seriously. At best, Sisters reminds viewers that just because a woman’s turned 30 doesn’t mean her life is over, or that she can’t accomplish great things. It won’t — and can’t — live up to feminist ideals, for the simple reason that it wasn’t designed to do so.

Nor should it have to. I suggest everybody simply watch the program in peace. These “sisters” have tall enough mountains to scale without having to live up to impossible standards of political correctness. And, besides, they’re putting on quite a show.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

This article was originally posted on the Sixth Tone on Friday, June 26, 2020. To read the full article, click here

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Wu Changchang.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.