An essay by Nora Amin that traces the presence of shadow theatre within the modern and contemporary Egyptian theatrical practices. From the analysis of the imaginative value of shadow, to the exploration of its aesthetic impact and its contribution to the contemporary notions of scenography and of liberating the Egyptian stage, Nora Amin presents a new examination of the connection that exists between the decolonization of the Egyptian stage, and the expansion of the theatrical discourse and form via the inspiration from the traditional sources of performativity.

Since its beginning, Egyptian theatre has tended to adopt the colonizer-perspective in defining theatre. Until now, the majority of theatre practitioners and scholars still prefer to look at the performing arts from the viewpoint of the West, decreasing the value of popular and folkloric arts. This perspective positions the folkloric arts as non-arts, or as practices of lesser and immature minds and imaginations, and therefore, practices that do not fit a modernist lens. Fortunately, there have been legitimate attempts within Egyptian theatre to venture in an opposing direction on this issue, whether through theatrical and performative endeavors or through studies and theoretical essays that are -unfortunately- seldom considered by the average reader or even by professional theatre practitioners.

In this essay, I will explore those exceptional practices and experiences. On one hand, I wish to identify that side of Egyptian and Arab theatre which could nourish current creativity and inspire it. On the other hand, I wish to create a connection between traditional resources and their representations in the theatrical modern and contemporary imaginary. The goal of such would be to encourage or stimulate new possibilities for the understanding of artistic imagination, imagery, and the aesthetics of the visual performative scene and their connections to other cultures.

At the beginning of our research, we encountered controversy regarding the roots of shadow theatre up for debate was whether it appeared first in China, Japan or Java, and how it moved to Turkey and Egypt. This controversy rests on the assumption that it had eventually appeared there due to geographic movement. At this point, we decided not to look for final answers, as it is not of vital importance for us to define the country where shadow theatre was born or initiated. Shadow theatre is not a concrete and material product/object. It is rather an art, an inspiration, and an imagination that cannot be really attributed to one single location. In fact, attributing shadow theatre to one country of origin could be a waste of time and effort, since we believe in the concept of a collective universal and intersectional imagination with threads interweaving between various cultures and popular creativities. Perhaps this concept is also useful for explaining the construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt as well as in ancient China, without claiming that the ancient Chinese have traveled to Egypt and imitated the construction of the pyramids, or vice-versa.

The collective popular and intersectional imagination can also explain several phenomena related to performance cultures – and to art in general- that belong to different peoples from different geographies when no evidence of imitation is present. For example, the discovery of the reflection of light, shadow and its play, are among the most ancient revelations of the human mind along its journey of maturity and growth. The development and investment of such revelation within the intentional fictional process varies from one popular/folk culture to the other, and from one tradition of visual consciousness and collective tradition to the other. Intersectionality between collective folk imaginations across cultures emerges from belief in the equality of the human mind wherever it is, and from the faith in its unity. This type of thinking is contrary to the common convictions founded within a hierarchal perspective that views cultural phenomena in terms of origin and replica, root and imitation, pioneer and follower. This very hierarchical perspective is the same perspective that exports to us the thinking that there is a certain center for art, or a certain destination for it. It is a type of thinking that does not differ much from the colonial ideology from which Egyptian and Arab artists have suffered. This ideology has deprived Egyptian artists of viewing their Western peers as friends and colleagues and has imagined those peers as superior, wielding influence over the possibilities of creative dialogue and artistic cooperation, and preventing the foundation of equality and a mutual fair imagination.

Egyptian artist and scholar, Nabil Bahgat, is considered among the most notable practitioners and thinkers in popular and folkloric performing arts in Egypt. He has extensive experience in researching and archiving those arts, experience that eventually led to his contribution to the acknowledgment of the Karagöz art form as a world cultural heritage by UNESCO. This is indeed a tremendous achievement that is due to Bahgat’s perseverance and expertise. Bahgat considers shadow theatre to have been far more popular with researchers in comparison to Karagöz art form. Many prominent scholars have written about shadow theatre, such as Waleed Hamada, and Mohamed Taymour with Games and Plays in the Arab region which resides alongside the studies of Ibrahim Hamada, Ahmed Abou Zeid, and Abd-El-Hameed Younis. Nonetheless, Nabil Bahgat considers Farouk Asaad’s Arab Shadow Play (Khayal Al-Zeil Al Arabi) to be the most important of all. In Arab Shadow Play, Assad tracks the history of the art form, nearly two thousand pages of the publication, making him the most important reference to Shadow Play in the whole Arab region. According to Bahgat, several scholars have found that Arab Shadow Play (literally meaning “Shadow’s Imagination”) was originally named as “The Shadow of the Imagination” (Zeil El-Khayal).

A Stranger in Paper City. Arab Origami Center & El Gecko con botas, 2019.

Many Arab scholars believe in early Arab theatre there existed a form of play called “The Story” (Al-Hekaya), wherein actors wore masks and specially designed and embroidered costumes. There exists a distinction between Al-Hekaya and another form of “Representational Story” (Hekaya Tantheliyya) wherein there was acting and characterization. This is also distinct from another form of “Narrative Story” (Hekaya Sardeyya) wherein there was only had verbal storytelling in a literary form without characterization and representation. At some point, Arabs adopted the name of “Shadow” (Khayal) to refer to the “Representational Story” versus the “Narrative Story.” The word “Khayal” (literally meaning both shadow and imagination), became connected to representation and characterization, and thus to performance. Later, Arabs began to utilize shadow as a visual factor within the scenery of a play. In this utilization, the shadow was connected to the performative imagery and imagination. On the linguistic level, shadow=imagination=performance, and this carries over to the creative as well. Thus, the performative practice was named “Khayal El-Zeil” (the imagination of the shadow), or acting with/through shadow.

Nabil Bahgat references this linear progression in examining the history and appellation of shadow theatre. He also draws our attention to the necessity of distinguishing between human shadow theatre (that depends on live human figures) and the other form of shadow theatre that employs puppetry, whether made of paper or of wood. One example that Bahgat refers to is of an artist -and artistic character- that appeared in the past: Gaafar the Dancer. The figure of Gaafar the Dancer emerges as a shadow dancer that spectators watch only via his shadow. Such a concept for dance with/through shadow unveils new horizons in understanding the Arabic aesthetic imagination and its connection to the human live body, as well as in understanding further potential for the artistic use of shadow in general.

Nevertheless, no one can accurately identify whether shadow theatre puppetry appeared before the live human shadow theatre, or after. However, the first confirmed description of shadow play art was made by the optician/scientist Ibn Al-Haytham (d. 1039) when he described a performance of Shadow Theatre which “appears from behind the screen”, and consists of “figures which the presenter moves in a way that their shadows appear on both the wall behind the screen and the screen itself.” Likewise, the first description of Gaafar the Dancer as a live shadow performer was in d. 1200 by the Egyptian poet Mohey Ibn Abdel-Zaher. We can gather from this that he must have appeared between 1039 and 1200, which is a relatively wide range of time, too wide to assume whether he appeared as part of the context of Ibn Al-Haytham’s observation of shadow puppets or later, or even before but without any documentation.

What remains important is that the words used to describe Gaafar created our modern visual rendering of his shadow dance. In other words, it is the verbal description that helped us to reconstruct the visual aesthetics of his dance. In the modern era, there are hundreds of images that reproduce the assumed posture of the shadow dance of Gaafar. Those images are captured throughout the twirling Dervish dance traditions across the Arab region. The open and extended arms to the sides at shoulder level form a fundamental part of the image of Gaafar the Dancer which is clearly an image connected to spiritual dance, Sufi dance, and to Sufism in general.

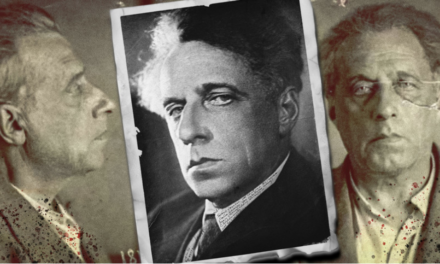

Ibn-Danial (the 7th century AH/After Hijra), is one of the most important figures in Arab Theatre history. Ibn-Danial traveled to Baghdad with the Tatar invasion, and from there came to Egypt; he is considered one of the founders of Egyptian theatre. His shadow theatre scripts can be seen as theatre plays, each of them representing the story of one shadow play/story. We join Nabil -and many other colleagues- in paying tribute to Ibn-Danial and honoring his work as a vital resource for understanding an alternative narrative for the start of Egyptian theatre. Referencing Ibn-Daniel is considered a drift from colonial interpretations and definitions of Egyptian theatre. Bringing him to the conversation leads us to wonder if it would be possible to start considering the sources of folk theatre and Egyptian popular spectatorship traditions as “performance cultures”. Further, would it be possible to regard shadow theatre and its scripts among the prime sources of Arab performance, within the orient and globally?…

This article was produced with the support of the European Union. The content of this article is the sole responsibility of the Arab Origami Center and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nora Amin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.