The Mayor of London’s 2008 practical guide to “Green Theatre” reported that the total carbon footprint of London’s theatre industry is approximately 50,000 tonnes a year. You would need to cultivate 3 million seedlings every year to offset this, equivalent to a plantation three times the size of Regent’s Park.

The report breaks down this total by department, stating that the majority of energy is consumed front of house (35%), while the heating and cooling of rehearsal spaces comes in second, at 28%. Theatre offices and stage electricals, such as lighting and sound, contribute 9% each, while overnight and pre-production theatre management are responsible for 6% and 5% respectively. Production materials–that is, set and props–contribute 5%. This breakdown excludes pre-production emissions and “indirect emissions from audience travel”–although since the latter is estimated at approximately 35,000 tonnes of CO2 every year, it is worth considering what spectators can do to travel to shows more sustainably.

Venues nationwide have been addressing in-house energy consumption with commitment and creativity in the last ten years. The dedication shown by backstage teams to reducing carbon emissions led me to wonder: What efforts are being made onstage to explore climate change? How does green practice in the conditions of production interact with representation onstage?

Joanna Reid, Executive Director of Coventry’s Belgrade Theatre, established a green policy for the venue as early as 2008. After watching Davis Guggenheim’s An Inconvenient Truth (2006), the award-winning film documenting Al Gore’s efforts to educate America about climate change, Reid reflected on her own environmental responsibilities. She saw an opportunity to apply the collaboration and imagination of her team to sustainable initiatives and called for volunteers from every department of the theatre to form a Green Team, which pooled information and oversaw the implementation of greener practices across the theatre.

These included replacing the three hundred 60-watt bulbs in the theatre’s iconic chandeliers with 28-watt energy-saving halogen lamps as well as the careful refurbishment of Red Lane, the theatre’s workshop facilities, during which a more energy-efficient gas boiler was installed that reduces gas usage by 36%. The Chamber of Commerce’s Carbon Trust in 2012 commended the Belgrade’s efforts, and the theatre’s six-point plastic waste reduction plan, announced earlier this year, has been greeted with enthusiasm by local publications such as the Food Covolution, a guide to independent food and drink businesses in Coventry.

Reid describes the difficulty of reconciling artistic practice with the Belgrade’s green policies: “Onstage artistic decisions are not taken with a green filter at all–all we can do is to provide the greenest equipment we can and to reduce its use when not required by the performance.”

Statistically, this makes sense: stage electricals and production materials contribute to only 14% of total carbon emissions in the theatre industry.

Yet as Una Chaudhuri, Professor of English, Drama, and Environmental Studies at NYU, writes:

By making space on its stage for ongoing acknowledgements of the rupture it participates in–the rupture between nature and culture…the theatre can become the site of a much-needed ecological consciousness.

Chaudhuri identifies site-specific theatre as a prospect for ecological theatre–productions that “directly engage the actual ecological problems of particular environments” and analogously provoke the audience to reflect on their responsibility to the global environment. Alternatively, Chaudhuri suggests the theatrical tradition defined by “its embrace of performance space, and rejection of setting,” exemplified by Robert Wilson and Heiner Müller’s Hamletmachine.

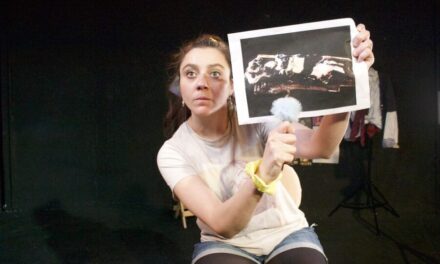

Jeff James’ production of La Musica at the Young Vic in 2015 explored these sites of ecological theatre by provoking the audience to consider the kind of event they were attending and “eliminat[ing] what was unnecessary in the production.” Marguerite Duras’ play is a two-hander about a couple revisiting their relationship. It does not deal with environmental questions directly. However, the production was staged as part of the Young Vic’s “Classics For A New Climate” series, an investigation into ways of making “more environmentally sustainable theatre” that began with a production of After Miss Julie in 2012.

Working alongside Julie’s Bicycle, a London-based charity that supports creative community action on climate change and environmental sustainability, the theatre aimed to reduce La Musica’s carbon emissions by 60%. La Musica generated 9.78 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (or CO2e, the standard measurement for carbon footprints) overall. This was 64% lower than the average of the theatre’s other productions that year and represented 2.5% of the Young Vic’s total carbon footprint for 2014–15.

La Musica was site-specific. The Maria studio, in which the play was performed, has a large window close to the ceiling that is typically blacked-out for performances. In this production, James and designer Ultz kept the window uncovered, and created a platform that allowed the performers to sit aloft and look out through the window during the first half of the play. The actors looking out of it were lit by the street lamps or daylight outside, depending on the time of the show, minimizing the need for artificial lighting. As the actors were required to sit with their backs to the audience in order to look out of the window, a video camera recorded their faces and a livestream was projected to the audience. The platform was accessed by a scissor lift, which the performers used to descend to the floor of the studio midway through the show, constituting a “scene change.” The production embraced the performance environment as an opportunity to create ecological theatre–as described in Chaudhuri’s essay.

The audience was challenged to interrogate their relationship to the theatre space by relocating halfway through the show. Initially seated on a balcony parallel to the raised stage and window, the audience was later encouraged to move down to the studio floor, taking up seats in an arena-style setup below. A pre-recorded video of audience members performing this action was projected to induce spectators to move–James chose to use a projector rather than a sound system during the show on the basis that the former used less energy.

By inviting the audience to dislocate themselves during the performance, James undermined the typically passive relationship between spectator and space of reception, drawing lessons from immersive or promenade theatre to perform an environmentally conscious activity. La Musica aimed to inspire a sense of agency in this relationship. The “austere” aesthetic undermined forms of representation that we customarily anticipate when we go and see a show, celebrating the efforts of backstage teams working to reduce material consumption for representational ends. Time for more creatives to meet them halfway.

Illustration by Jade Delmage

Eleanor Warr is a theatre director and a writer. She graduated from the MA Text and Performance programme at Birkbeck, University of London and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in 2018. Eleanor was the director of the Cambridge Footlights International Tour Show in 2017, an annual touring sketch show, written and performed by students from the University of Cambridge. Eleanor was the assistant director on Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella, directed by John Martin at the Trinity Theatre, Tunbridge Wells. She has directed at The Cockpit, Camden People’s Theatre, The Roundhouse, Pleasance Ace Dome and Paradise in the Vault (Edinburgh Festival Fringe). She is the editor of the Theatre and Performance section of It’s Freezing in L.A.! (IFLA), an independent magazine with a fresh perspective on climate change.

This article was first published in It’s Freezing in LA! (IFLA, 2018:1, Temperature), an independent magazine about climate change. It has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eleanor Warr.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.