In this day and age, the word data evokes preconceived images of algorithms, artificial intelligence, and big data, especially as many of us rely more and more on computational devices to access digitized information. This is, of course, a narrow, relatively modern definition of the term: Data also denotes, more broadly, knowledge and information given, processed, and transmitted. The medium of such data may range from a sensing device like a camera to a physical body, which also senses and processes the stimuli we feel in relation to our surrounding environment. How does contemporary dance grapple with the changing meanings of data, even as artists deconstruct and reconstruct the values of human dancing bodies vis-à-vis the emergence of machine learning and artificial intelligence in the arts?

Sense Datum, a new work choreographed by Lee Nahyun as part of the Seoul International Dance Festival, staged at the Daehakno Arts Theatre Grand Auditorium on September 14, 2023 in Seoul, South Korea, asked just that. The 2023 festival’s theme was “body and aging,” allowing for a discursive space that could broadly engage with kinesthetics, posthumanism, and automation of dance movements. In this context, Sense Datum carefully laid out the many folds of the choreographer’s sincere exploration into the latter and more capacious concept of data I mentioned above through a series of solos, duets, and group dances based on contact improvisation. That is, it investigated how the body itself becomes a sensing device on stage in a contemporary choreographic form, without necessarily resorting to using computational devices to express the meanings of data in dance. Those expecting to see choreographic experimentation with visually striking and technologically sophisticated uses of computational devices on stage may have perceived this attempt as slightly jarring. Indeed, other dance works featured during the festival applied artificial intelligence to the emerging interconnectivity between contemporary dance, data science, and machine learning in a more obvious way. For instance, Kim Hea-yeon’s Technology of arTaGame centered dancing bodies’ interaction with ChatGPT.

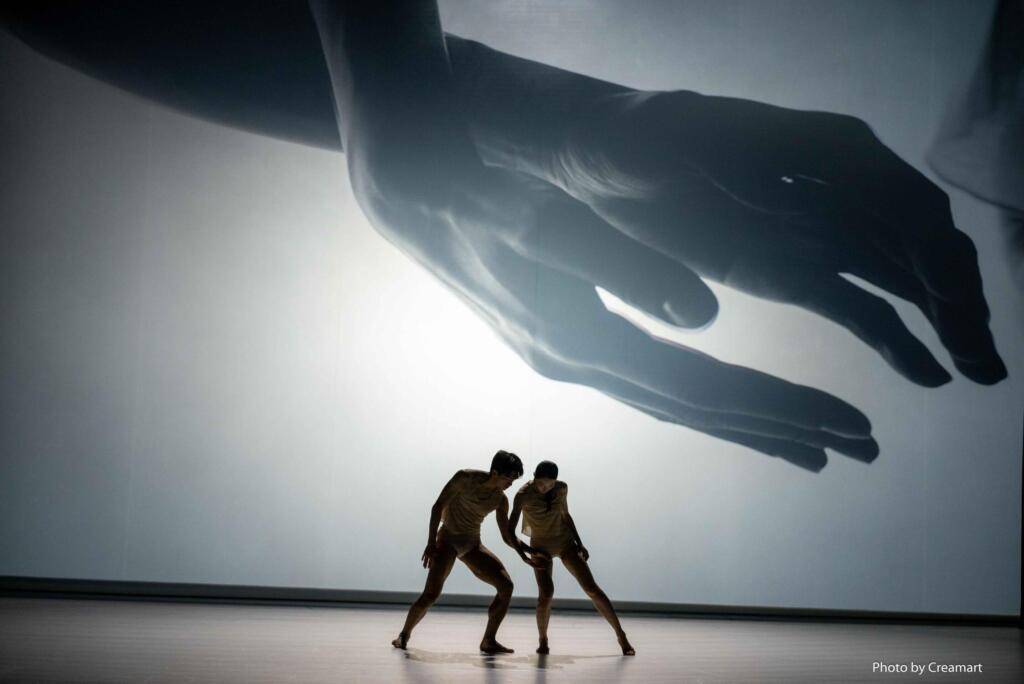

However, Lee Nahyun’s work was anything but tech-savvy. In fact, there was no noticeable uses of technology or computational data except for projections of simple images of sonic reverberations or dancers’ hands ever so slightly touching one another on the backdrop. The entire one-hour-long performance presented a series of simple steps and familiar moves including push-and-pull movements between two or more performers, contact improvisation-based sequences, and dancers aligned in a single line for a group dance work. All seemed familiar, like many other examples of the modern dance repertoire based on Jaques-Dalcroze’s eurhythmics, which build choreographic sequences on non-balletic steps responding to basic musical rhythms and structures.

Sense Datum began with dancers huddled on the floor at the center of the stage. With no lighting focused on them, they formed what looked like a small black hill, ever so slightly bobbing up and down from the dancers’ collective breathing. The stage was completely bare and white, the only noticeable visual component being a large screen upstage onto which a moving image of fog was projected. The background sounds of someone slowly inhaling and exhaling were not musical yet they had their own unique melodic flows. The deep breathing sounds were supported by atmospheric music shaped by a sustained A note. The sustained A note was played throughout the performance, sometimes in synthesizer-based ambient music or acoustic piano sounds. The minimal background music and the repetition of the continued A note enabled the audience to focus on the dance movements only, even as the sounds were in constant dialogue with the dance.

Sense Datum. Image courtesy of UBIN DANCE @creamart

From the huddle, the dancers slowly stretched their limbs before rolling towards stage left and right, disappearing into the wings. Only two dancers remained in the center, lying sideways and about five feet apart, trying to reach each other’s hand (but never really touching) by stretching their arms and making an arch-like shape. This represented the very motif that ran throughout the performance: the meaning of contact, and what it means to sense others’ energy only through kinesthetic relationality. Through the many variations of contact as a central motif, the choreographer seeks to understand bodily movements in their original state, way before they are sensed as assembled and interpretable datasets, and before they are even named and coded as choreographic gestures. That is, the question at the heart of stretching these basic gestures into iterations was: How do the spectators and the dancers gradually become involved together in the performative process of recognizing, ordering, interpellating bodily movements? And what happens when we purposefully strip ourselves of these habits of being consciously observant of dance moves?

Sense Datum. Image courtesy of UBIN DANCE @creamart

In another aspect, Sense Datum also contemplated how energy and affect were transmitted as data kinesthetically without bodily contact. After the initial five-minute sequence that introduced the concepts of sense, energy, touch, and contact, the two dancers continued to experiment with bodily encounters. Every time their hands or arms were near one another or finally touched, the A key was heard in staccato piano notes with prolonged reverberations, as well as through the sounds of piano hammers. Meanwhile, the pre-recorded video projected onto the backdrop showed close-ups of the dancers’ hands or legs as they got near one another. If touching or contact is understood for dancers as a primary means of understanding and bringing another dancer’s kinesthetic presence into a more concrete form (as when they brush up against another dancer’s arm, lie down on top of another dancer, or run towards and clash into one another), the choreographer here quietly interrogated the value-making of contact itself in contemporary dance, constantly bringing both the audience and the dancers’ attention to the very moment of touching that never quite actually happens.

Sense Datum. Image courtesy of UBIN DANCE @creamart

If the recurring theme asked what deferred contact means in contemporary dance, another theme was explored throughout the work by grouping dancers into contact improvisation-based duets, trios, and quartets. Here, too, the dancers did not simply gather. Instead, the groups involved moments of hesitation to reach out or surveying one another’s intentions before finally making contact. They took their time to approach one another with slow steps, sometimes raising the other dancer’s arms and examining them before finally holding onto them. Once again, while duets and trios of dancers investigating tensions and energy among one another may be a familiar idiom in contact improvisation, these subtle breaks invited the audience to contemplate what it means to sense and know the other on stage, as a kind of datum.

If the first half of the performance featured slowly unfurling gestures of reconnaissance, transmission, and kinesthetic exploration, the second half was more assertive in terms of the fast pace and the range of motions that the dancers offered—twirling, sliding on stage, and charging at other dancers. A dimmed, off-white light shone upon a semi-circular downstage area of the completely bare stage, where most of the motions played out. The group dynamics among the nine dancers added yet another interesting layer to the performance, where the rest of the performers observed and sometimes mimicked the duets and trios, creating a cypher of sort.

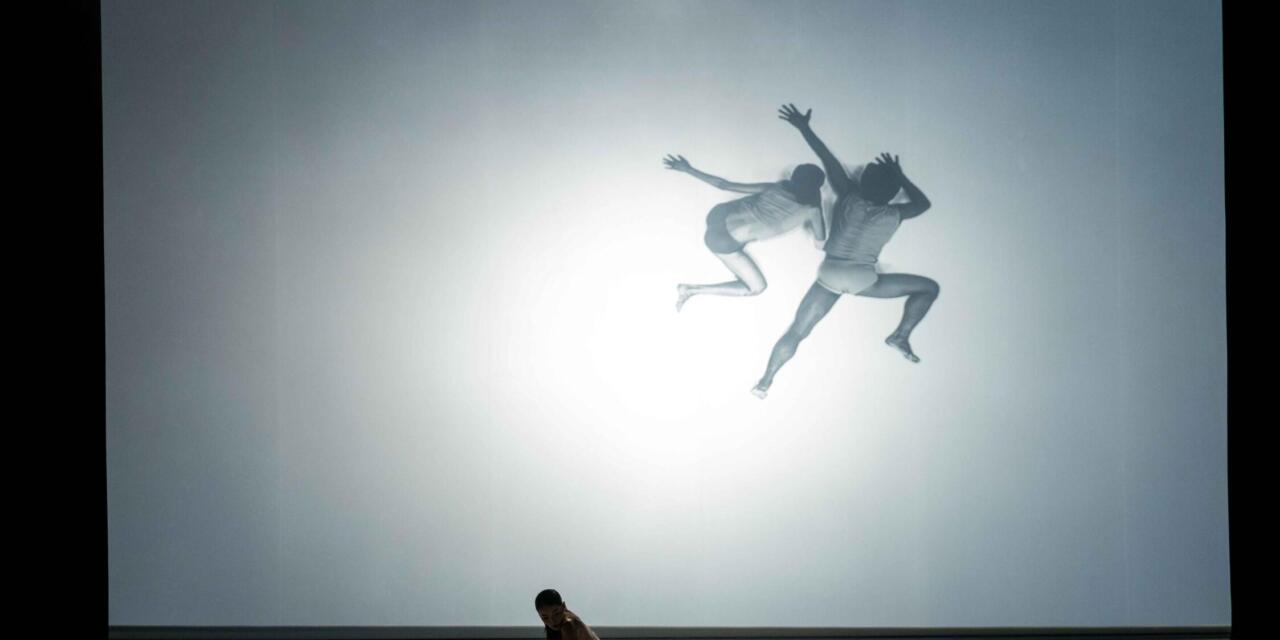

Sense Datum. Image courtesy of UBIN DANCE @creamart

The final scenes featured all nine dancers in pinkish nude sleeveless shirts and shorts, bringing the audience’s focus more sharply to the dancers’ bodies. Standing in one line facing the audience, the dancers created waves and bridges in an interlocking manner with their arms and hands connected to one another. At first glance, this may seem like a dance form from a bygone era, lacking the usual abstract and conceptual style that we expect to see in avant-garde contemporary dance. However, the performance reminds us that the expansive range of conceptual avant-garde choreographies commonly practiced today is also rooted in these building blocks of basic dance movements, which are often considered outdated in South Korea’s contemporary dance scene. The shadowy, enlarged figure appearing behind the dancer center stage in the last five minutes of the performance perhaps embodied just that: the specter of dance that challenges assumptions about contemporary choreography.

Sense Datum. Image courtesy of UBIN DANCE @creamart

This brings me to some afterthoughts about the current state of the arts in South Korea, where ChatGPT, AI, and algorithms are becoming buzzwords in the arts scene. Even government funding bodies and institutions have become increasingly susceptible to the profitability and faddishness of the trends, without necessarily providing artists with substantial means and support to actually research the relationship between dancing bodies, data, and technology. Given this environment, Lee Nahyun’s work ironically came across as bold and novel. The performance was an investigation into the capacity of dancing bodies, pushing against whatever preconceived notions about contemporary dance we as audience members may have brought over to the venue. The choreographer asked how dancing bodies could help us rethink the kinds of kinesthetic experiences activated by dance, and how they are distributed, articulated, and built upon the dynamics of dancers, before such data is imbued with the array of codified meanings and significations of movements that we call contemporary dance. Sense Datum convincingly demonstrated that contemporary dance and its knowledge transmission are all about sensing the body’s layers of information and affect, with or without technological devices.

Choreographer Lee Nahyun ⓒBAKI

Credits:

Choreographer: Lee Nahyun

Performers: Ryu Jin-wook, Kang Yo-seop, Lee Ji-yung, Shin Hye-jin, Kim Hyea-yoon, Kim So-hye, Seo Bo-kwon, Son Ji-min, Park Seong-hyeon

Composer & Piano: Heo Dae-uk

Sound Designer: You Tae-sun

Lighting Designer: Kong Yeon-hwa

Visual Art & Photography: A APOLLON BAKI (Park Gwui-seop)

Stage Manager: Kim Jin-tae

Costume Designer: FONDATION_CYT (Choi Yeong-tak)

Producer: Jung Hye-mi

Studio Photography: Aplan Company

Director of Photography: Kang Pil-jin

Assistant Director of Photography: Lee Sang-jae

Studio Lighting: THE LIGHT

Lighting Director: Lim Chang-uk

Lighting 1: Sung Jin-hwan

Lighting 2: Park Kwang-ho

Lighting 3: Yoon Chang-hwan

Hosted by Seoul International Dance Festival, Lee Nahyun

Organized by UBIN DANCE, Art Project by Yunseul

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Soo Ryon Yoon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.