One of the great subcontinental migrations, and one that has arguably been slowly erased from public memory, provides the backdrop of a new play from director Gerish Khemani, based on a script he co-wrote with Akshat Nigam. Written in English, with a smattering of Sindhi, In Search Of Dariya Sagar won Nigam and Khemani the Hindu Playwright Award last year.

The play, about a third-generation Sindhi, Jatin Sadarangani’s quest to uncover his cultural connections with a past he is scarcely acquainted with, uses the Partition of India and the devastating displacement of communities it engendered as a frame of reference.

Building blocks

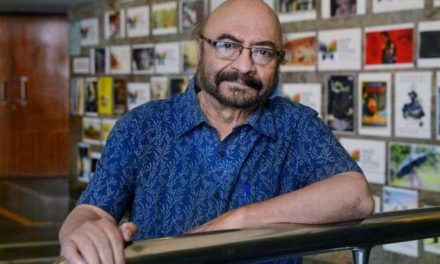

The play arose from Khemani’s own grappling with his Sindhi roots. He had grown up estranged from his origins, conflicted about prevailing misconceptions about Sindhis, and had internalized a marked disavowal of his cultural identity. During a three-month stint at the London International School of Performing Arts in Berlin, he was part of a multicultural classroom in which drama students were encouraged to work in their native tongues. “I was flummoxed by my non-existent relationship with Sindhi among Europeans who expressed themselves so freely in their own languages,” remembers Khemani, who thinks and speaks primarily in English.

He likens it now to a colonization of the mind, not because he feels alienated with his own culturally assimilated self, but because that assimilation came at great cost—the obliteration of roots that has possibly afflicted an entire unmoored generation. The sense of an irrevocable loss set him on an extensive journey of deep excavation, both anthropological and introspective, partnered with Nigam who, not being Sindhi himself, perhaps provided an invaluable alternative perspective in the building of the play’s fictional structure. Tulika Bathija, a researcher heavily invested in investigating her origins, was a consultant who participated in the early brainstorming.

Khemani’s grandmother hailed from Thatta, in Pakistan’s Sindh, which is believed to be the birthplace of Jhule Lal, the revered community deity who manifests himself throughout the play. The poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, virtually poet emeritus for Sindhis, is sung live by intrepid actors who play multiple characters. The Colaba-bred Sadarangani (played by talented Dheer Hira) shares much of the director’s existential angst and yearning for truth. “Yet he is a much darker, even crazier, manifestation of me,” says Khemani, of the work’s semi-autobiographical elements.

He has assembled actors who are makers themselves, owing to the need to experiment with theatrical form while making the transition from page to stage. “We have evolved a physical text that will both supplement and challenge the written script,” he explains. Some of the actors, like Hira and Vaishnavi Ratnaprashant, have worked with Khemani on his previous play, Ripples.

Forgotten histories

The team’s research unearthed the remarkable history of a resilient community. Despite tremendous reversals of fortune, the Sindhi pioneers laid the foundation of thriving enterprise and cultural capital. All of this spectacularly shattered Khemani’s preconceived notions. “Even as a 32-year-old, I haven’t yet explored a wealth of literature that remains untranslated and therefore obscured,” he rues.

Yet the winds of change may be in the offing. Bathija recently attended a cultural program at the Jai Hind College and was struck by the young students who seemed to revel in Sindhi culture like never before. She termed it a cultural resurgence, whose time had perhaps arrived. Khemani feels that their play is an interjection in the same direction. He cites Sapna Bhavnani’s documentary Sindhustan: Lost In Translation and Nandita Bhavnani’s The Making Of Exile: Sindhi Hindus And The Partition Of India as important works that might well spark off a Sindhi renaissance. The title of the play refers to the Indus, along the banks of which the community once thrived. Known for its duality, sometimes inundating valleys and sometimes reduced to a trickle, in the play the river becomes a metaphor for continuity — of land, culture, and identity.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on July 20, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.