In one lifetime, the many loves that once dared not speak their names have become part of everyday chatter. But it would be shortsighted to believe that ancient prejudices are easy to overcome, or that change does not run the risk of creating new problems. In this latest play, Wife, Samuel Adamson explores several decades of the trials and tribulations of forbidden love in a piece of the epic theatre that is also exquisitely personal. At the same time, he has also penned a fan letter to the theatre, taking Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House as a template against which to measure social progress.

Each of Adamson’s decade-hopping scenes begins with a different production of Ibsen’s play, which is briefly glimpsed in a variety of guises — from traditional costume drama to postmodern cross-dressed mash-up — and the theme of marriage, and what it both signifies and feels like, ripples through the evening. So A Doll’s House, one of the modern drama’s great examples of a feminist-influenced criticism of bourgeois marriage, is repeatedly and pleasurably brought to our attention, reminding us that great plays sometimes have the power to change social attitudes (for good or ill). What makes this juxtaposition of a modern classic with different social contexts so pleasurable is Adamson’s writing, with its sparkling dialogues, joy in-jokes, and acute insights.

The story starts in 1959: actress Suzannah is in her dressing room after playing Nora in Ibsen’s play and is taking off her make-up. Her one-time lover Daisy, who has been in the audience, comes backstage, along with her new husband, Robert. Daisy loves the play, but Robert hates it: there’s a passionate discussion about Ibsen’s message of female independence, and then a more intimate dialogue between the two women as they discuss their feelings for each other. The issues raised include the question of how you think about marriage: is it a true meeting of minds, or a prison house with two jailers? Is theatre a safe place for sexual outlaws, or just an escape from reality?

These themes are then restated in 1988 when Ivar — Daisy’s son and a gay activist in the AIDS era — has a heated argument with Eric, his 20-year-old and therefore technically underage boyfriend. In 2019, it is the turn of Clare, Eric’s daughter, to meet the now aged Iver in an attempt to understand her recently deceased father, a scene which also involves Clare’s fiancé Finn and Iver’s hyped up young lover Cas. By now, the old worries about closets have been replaced by new anxieties about metrosexuals, gender neutrality, and transvestite art. All of which set the scene for a sci-fi leap into 2042, when Clare’s 22-year-old daughter Daisy finds herself, in a wonderful moment of harmony as future echoes the past, backstage at another performance of A Doll’s House.

Just as Nora’s original slamming of the door on her marriage in 1879 caused cultural ripples all over Europe, so Adamson’s thrillingly written and often joyful play is full of echoes as each scene is a thematic recapitulation of the previous ones. Phrases, attitudes, sentiments, and ideas repeat and fizz in a kind of gymnasium of the imagination which throws queer lives against theatre history in a brilliantly alive series of meditations on identity and life choices. And Adamson controls our expectations with consummate skill. In the first scene, Nora’s tambourine is scribbled on, but we have to wait until the last one to know what has been written on it.

What keeps us going is Adamson’s dazzling skill at presenting intense arguments between convincing individuals, with added layers of dramatic irony and hindsight. A key image is an idea that both hetero and gay marriage are prison cells, in which both partners are deprived of their freedom, either by social laws or by their own possessive instincts. If so, then the image of Nora’s walkout retains its potency as a symbol of freedom, even if it solves few of life’s mundane problems. Variations on this idea are played out also in the passages about theatre as a “prison with velvet curtains” (or is it an escape?), while the sub-theme of medicine is suggestive of healing and redemption. In a text that bubbles with perception and illuminating declarations, there are name checks that remind us of the wider political picture: from Enoch Powell to Brexit.

As its name indicates, Wife is a drama that both examines the damage that such a role can do to women, and at the same time shows how this partner status can mutate and change over time. At first, the subordinate status of the wife is a result of patriarchy and being female; but later this hierarchy is reproduced by means of age, experience, and force of character. In our more gender fluid era, different questions might arise, but the struggle to assert our own personal identities and hold onto a sense of our own liberty can still be pretty challenging. Even when they are no prohibitive laws to cope with, our own frailties and our own prejudices can spoil personal happiness. Using a mixture of humour and well-focused passion, Adamson explores all this in a piece that has a breathtaking range and an excitingly ambitious scope.

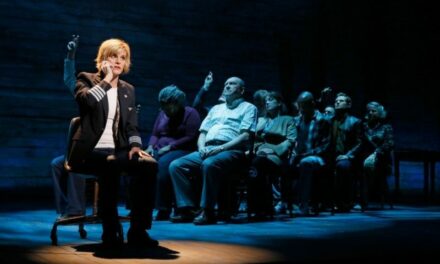

Indhu Rubasingham directs with focus and intensity, with Richard Kent’s set and David Shrubsole’s music creating all the ambiance necessary to tell this epic tale. A hard-working cast play several roles each, which brings alive the alarming sense that sexual transgression is almost genetic and helps set up some of the drama’s thematic echoes. Karen Fishwick (Daisy and Clare) has a brightness and vulnerability that contrasts well with Sirine Saba’s more worldly and cynical Suzannah, while Joshua James’s delightful young Ivar and grim Robert play well against Richard Cant’s older Ivar. Calam Lynch is great as both Eric and Cas, bringing markedly different qualities to his portrayal of the two men. The end result is an evening both humorous and thought-provoking.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk.

Wife is at the Kiln Theatre until 6 July.

This article was originally published on http://www.sierz.co.uk. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.