Watching a long-awaited theater premiere live on your iPhone instead of being in the auditorium (as originally planned) is an unusual experience. But when it’s one of Heiner Muller’s plays and COVID-19 news notifications keep popping up on your screen every few seconds, it’s nothing short of surreal.

After being ordered by the Ministry of Culture to shut down due to the spread of coronavirus last week, Russian theaters are following in the footsteps of their international colleagues and massively going online. They adjusted to the new restrictions in record time. Releasing your archives, as well as playing all scheduled productions for a few cameras and a bunch of potential social media users has quickly gotten old. All the upcoming premieres were now to be live-streamed. And some theater companies went as far as holding online theater festivals.

Now, as part of Brus Home Fest, organized by Moscow’s Dmitry Brusnikin Workshop (Masterskaya Brusnikina) theater, you can do your morning workout with one of the actors, watch their chess match, have dinner with them and, of course, watch one of their productions. While #NOINTERMISSION (#BEZANTRAKTA) festival, St. Petersburg governor’s office’s initiative, will live-stream events from the city’s major theaters and museums.

Out of them all, Alexandrinsky Theater (commonly known as Russia’s first public theatre) in Saint Petersburg was one of the first to announce their plans for the period of quarantine. In addition to a bunch of regular events, the theater decided to live stream both of their upcoming theater premiers: Theodoros Terzopoulos’ Mauser on March 21 and 22, and Andriy Zholdak’s Nana in April.

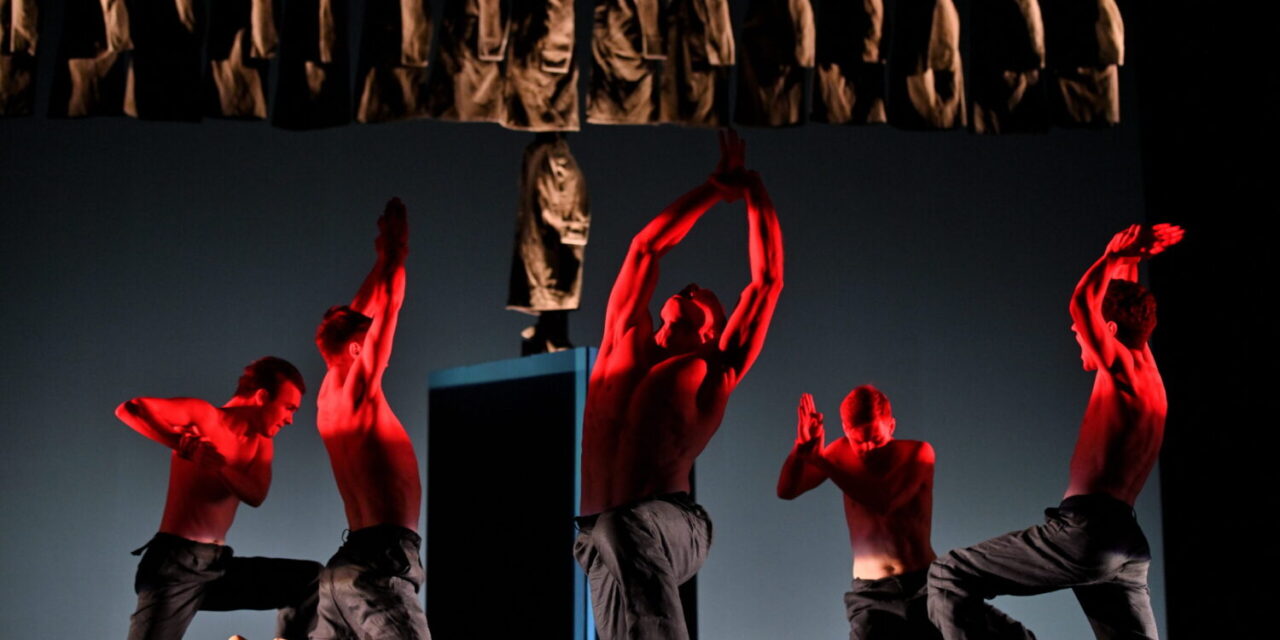

Nikolay Marton (The First Victim), Nikolay Belin, Maksim Yakovlev, Timur Akscentcev, Vladimir Malikov, Evgeny Kochelev (The Accused) in Mauser by Heiner Muller. Directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos for Alexandrinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo by Vladimir Postnov.

To bring Mauser to Russian theater-goers’ smartphones and Smart TVs, the theater teamed up with the country’s leading satellite TV service Tricolor TV. An ensemble of 17 actors ended up performing for an empty auditorium, with the potential of reaching millions.

Terzopoulos’ Mauser became the first staging of Heiner Muller’s play of the same name in Russia. Despite his international acclaim, the playwright’s name is not widely known here. It was Terzopoulos, who in the 1990s introduced Russian theater-goers to Muller’s imagistic style, putting on his Quartet for Taganka Theater.

Terzopoulos and Muller go back a long way together. In the 70s, the Greek theater director spent five years working at the Berliner Ensemble, with the playwright as his friend and mentor. According to Terzopoulos, it was Muller, who reintroduced him to Greek tragedy and made the director question what it means to be human.

The Accused in Mauser by Heiner Muller. Directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos for Alexandrinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo by Vladimir Postnov.

Human nature is Mauser’s main theme. Loosely based on Mikhail Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don and Isaac Babel’s Konarmiya, it tells the story of one’s inner struggles at the time of civil war, when a man becomes nothing more than an instrument in the hands of the revolution. Once he realizes the pointlessness of thousands of innocent deaths at his hands that became one with the gun (‘Why all the killings If the price of revolution is revolution If the price of freedom is those that ought to be freed’), the revolution considers him an enemy of the state and demands his death (‘The revolution needs you to say ‘yes’ to your own death’).

“The play unfolds the dynamics of violence that are revealed in the course of a revolution, distancing it from the original purpose and making its achievement nearly impossible. In such a setting, revolution as a social phenomenon, apart from its political traits, takes on a deeply humanistic and even ontological side,” says Terzopoulos in an official statement.

Elena Nemzer (The Judge) in Mauser by Heiner Muller. Directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos for Alexandrinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo by Vladimir Postnov.

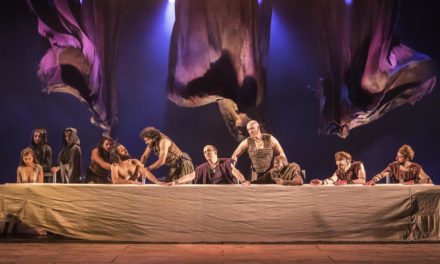

In Terzopoulos’ production, action spills from the stage to the auditorium, where the chorus is split into two parts that are set against each other, visually resembling a traditional courtroom setting and channeling both Brecht’s and Greek theatre (Set design, costumes and stage lighting by Theodoros Terzopoulos). The Judge (Elena Nemzer) reigns over them, covered in over-the-top jewelry with a massive crucifixion hanging down her neck. She is the voice of the revolution. Behind her is another crucifixion made out of the victims’ bodies, at the feet of her stand are the Accused (Nikolay Belin, Maksim Yakovlev, Timur Akscentcev, Vladimir Malikov, Evgeny Kochelev). Bare-chested and tense, they replicate killing moves: holding their hands out like a gun, piercing bodies with an imaginary sword and choking themselves. Their words turn into chants and then animalistic howls.

Igor Volkov (The Instructor), Nikolay Belin (One of the Accused) and part of the Chorus in Mauser by Heiner Muller. Directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos for Alexandrinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo by Vladimir Postnov.

The way the actors work with their bodies and voice is distinctive of Terzopoulos’ acting method that centers around the use of the diaphragm to extract sound. The chorus is sitting in the now-empty auditorium, accompanying the so-called theatricalised oratorio with rhythmic sounds, religious hymns, and revolutionaries’ songs. Among them sits the first victim, halfway through he’ll get dressed in a bourgeois coat and hat with lips painted red to be killed on stage. The theater’s oldest actor and Terzopoulos’ regular Nikolay Marton plays the part.

Mauser is Terzopoulos’ fourth production at the Alexandrinsky theater. It forms a dilogy with his 2017 staging of Brecht’s Mother Courage and her Children. His previous productions are Sophocles Oedipus Rex (2006) and Beckett’s Endgame (2014).

Nikolay Marton (The First Victim) in Mauser by Heiner Muller. Directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos for Alexandrinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo by Vladimir Postnov.

The actors are not overly bothered by the absence of the audience, although Igor Volkov, who plays the Instructor, admits in an interview before the show that “it’ll be difficult to motivate yourself for an empty auditorium.”

From the spectator’s point of view, while it’s a generous move on the part of theaters to let their quarantined audience watch the theater premieres from the comfort of their homes, it can in no way compare to the real thing. Once danger is out of the way and the quarantine is over, theaters should expect an influx of visitors hungry for some real-life action. Or at least we should hope this would be the case, for some fear that the damage COVID-19 has caused to the creative industry in Russia and internationally might already be beyond repair. Only time will tell.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Karina Verigina.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.