Russia is my country, who better than me to clean up the ruins of our humanity. – Elena Kovalskaya

Elena Kovalskaya

Elena Kovalskaya is a theater critic, curator, and producer. She was born in Kerch, Crimea, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and lives in Moscow today. She studied and now teaches at the Russian Institute of Theatre Arts. She is a Director of its MA program in Social Theatre. In the past, she worked as a columnist and editor of Afisha magazine. As a curator, she used to run the Lyubimovka Festival for Young Playwrights at Teatr.Doc, the New Drama Festival, and the Documentary Theatre Project in the Russian Regions entitled Live Theatre – Live Author and others. From 2012 till February 24th, 2022, she worked as the managing director of the Meyerhold Theatre Center (TSIM), Moscow.

We begin this interview 40 days into the Russian invasion of Ukraine: I am in the safety of my Canadian home and Elena Kovalskaya, the former managing director of Moscow’s TSIM, in Moscow. The day the war started, on February 24, 2022, Elena performed an act of personal heroism – she resigned from her position in protest of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In a post she shared on Facebook, Elena wrote “Friends, in protest against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I’m leaving my post as Director of Moscow’s Vsevolod Meyerhold State Theater and Cultural Center. It’s impossible to work for a murderer and collect a salary from him.”

Elena Kovalskaya is one of those Russian artists and theatre makers, who for many years tried to resist the regime, which slowly but surely has been spreading its power in preparation for the current invasion of Ukraine. Within this trajectory of resistance, the artistic, managerial, and pedagogical work of TSIM occupies a special place, and so goes my first question.

Yana Meerzon: Elena, TheTheatreTimes is an international platform for theatre news. For many of our international readers, the name of Vsevolod Meyerhold or the history of the Moscow’s Meyerhold Theatre Center, and its internal connection to Meyerhold’s work and his memory are not fully evident. So, let’s begin our conversation with a short historical voyage into the making, the development, and the closing of TSIM, which took place only a couple of days after you stepped down from your position.

Elena Kovalskaya: TSIM was created in 1992 following the initiative of Valery Fokin, who spent his career in the Russian director’s theatre. In the early 90s, however, Fokin decided to create a new type of theatre, without a permanent repertoire-based company. Fokin dreamed of resurrecting the legacy of Vsevolod Meyerhold; and so, he wanted to create a kind of festival venue in the centre of Moscow, with a stage-transformer, almost like a black box, to provide space for theatrical experiments.

By the time Fokin started working on this idea, the dominant theatre form in Russia was a vertical or director’s type of performance making. An imperial building with a proscenium stage type was its leading architectural format. Fokin was interested in reviving the experimental format of theatre-making, which started with Meyerhold’s work in the early 1920s. Much like Meyerhold himself Fokin was interested in the questions of theatrical form and how it could be used to express political content.

His other influence was the theatre theory of Antonin Artaud, who in his own time searched for non-mimetic theatre practices, and immersive and participatory experiences. At the same time, in his search for the experimental theatre language, Fokin appeared as a true product of the Soviet theatre school. He firmly believed in the hierarchy of directorial theatre, whose artistic innovations must be supported by substantial budgets and elaborate sets. TSIM, as it was envisioned by Fokin, was to become a theatre laboratory, to help emerging directors advance their professional skills. Fokin established a Russian Guild of Theatre Directors and MFA in Directing at Moscow Art Theatre’s school, whereas TSIM became a place for emerging theatre directors to experiment with different theatre spaces, not just a proscenium stage, and it welcomed new collectives to present their work.

So, one could say that TSIM was the product of the atmosphere of collaboration and experiment, which continued in Russia through the early 2000s, till the end of Medvedev’s presidency (2008-2012), widely known as a period of modernization.

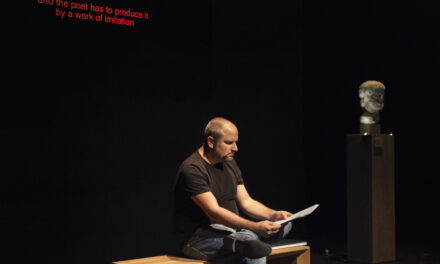

Motherland, director Andrey Stadnikov, photo credit Ekaterina Kraeva.

Financially, TSIM relied both on state funding and private capital, a model of economic partnership, which was also put forward in the early 90s. In 1992 the Moscow City Council, with Yuri Luzhkov, Moscow’s mayor at the time, supported this initiative, whereas a famous producer Alfred Lerner proposed to construct a new complex, which included a business center, a hotel, and a cultural center, known as TSIM today. In 2003, a war between the owners of the building broke out, during which Lerner was killed. After that TSIM was converted into a state-run theatre institution, with its funding coming from the Moscow budget local and the federal resources.

The situation drastically changed with Putin returning to power in 2012. The famous protests that took place on Bolotnaya square in Moscow in 2011/2012, when Russian people went on the streets to express their free will and insurrection, their dissatisfaction with the falsified results of the election, was a special moment in Russian history. One can say, in 2011 Russia woke up as a society of citizens, who suddenly realized that they shared collective responsibility for the war in Chechnya, Georgia, and for the disappearance of liberal and democratic institutions of justice. The creative class went into resistance; it emerged as the pillar of protest against the regime.

As we know, however, the protests on Bolotnaya square did not bring desirable results. Upon his return to the presidency, Putin announced a conservative course and began to build up his repressive machine. Cultural policy became a policy of financial blackmail and censorship, hidden behind so-called public opinion.

At the same time, the generational gap between the older theatre managers, those who used to manage cultural institutions yet in Soviet times, and the younger ones, those who could resist the new politics but lacked experience, became too apparent. Moscow’s Minister of Culture, Sergei Kapkov came to the office at the end of Medvedev’s period of modernization. His task was to radically change this theatrical environment. But he did not have a plan for how to do it. He understood the call for a change of generations literally and decided to simply replace older theatre managers and producers with the younger cohort, promoting those in their early 30s into the governing positions.

With the last wave of modernization, Viktor Ryzhakov took over as TSIM’s Artistic Director and I joined his team as A Deputy Creative Director, along with a group of young theatre-makers who used to work in the independent sector. We saw TSIM as a venue for a new school for theatre leaders, who could respond to the needs of the new financial and artistic systems as implemented by the Russian government. This educational program was to bring together people of different generations and skills – including directors and critics, theatre managers and artists, journalists, academics, and sociologists. These specialists were to challenge the system of directorial theatre and imagine a more dynamic, inclusive, and diversified scheme of theatre leadership, based on the so-called horizontal not vertical forms of governance, both in the rehearsal hall (artistically) and outside it (financially and contractually). This educational scheme, which TSIM run for 3 years with 130 students in it, was based on the model of strategic planning as set by the Kennedy Centre in New York.

For the economic and artistic culture of the post-Soviet theatre, this educational program was unique, and it allowed the artists and the managers to implement the systems of governance based on the idea of theatre guilds and artistic competition. By the time this program was implemented, a much older scheme of vertical theatre management flourished, with many artistic and financial directors leading their companies for dozens of years, without planning any personal retirement or preparing for generational change. When the young team of TSIM came together to challenge this system, it aimed at dismantling the idea and the practice of this old vertical scheme. These new managers wanted to contest the omnipresent power and position of an artistic director. They fought against political and managerial corruption, seeking for rotation of power, transparency in hiring, and clear strategic planning. TSIM’s program privileged applicants who had experience running independent businesses. The goal was to provide them with access to state-sponsored theatre institutions and teach them how to shake the system from within and fight nepotism.

Artistically, TSIM preferred working with independent theatre companies, which did not receive funding from the government. To TSIM’s management, these independent companies exemplified true places for artistic, social, and political experiments. In the early 2000s, the Russian independent theatre movement actively advocated for diversifying theatre work and politics: it welcomed new theatre companies for children, feminist groups, socially inclusive theatres, theatre-making with prisoners, and so on.

In other words, before the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas in 2014, TSIM and our artistic team firmly believed that our generation of theatre-makers and managers are given a chance to radically change the existing system of theatre-making in Russia, and introduce new ways to do art – based on democratic forms of development.

This is Part I of the two-part interview. To read Part II, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yana Meerzon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.