In spite of all open-mindedness, attending family performances as an adult can be, initially at least, off-putting. There is a stigma around the themes approached, the aesthetics, and the acting methods as well, that might be difficult to overcome once you’ve experienced, almost uninterruptedly for years, only generalist theater. The “friendship conquers all, Romeo&Juliette-esque” plot, however, can be conveyed in a multitude of ways, and the quasi-explicit character of productions aimed towards a younger audience can prove itself beneficial in the case of being faced with a strong language barrier.

There is one more aspect to be highlighted: the concept of stratification in age-determined theatrical creations. No writer or director can guarantee any level of attention from their young viewers. The targeted participants (aged 7 and above, in this case), however, are accompanied into the halls, and this diversifies the public’s levels of understanding. Jokes, socio-economic or political references, (still) inaccessible to the kids, provide the performance not only with artistic depth, but also with an engaged adult audience, in turn generating a subconscious higher interest from their children.

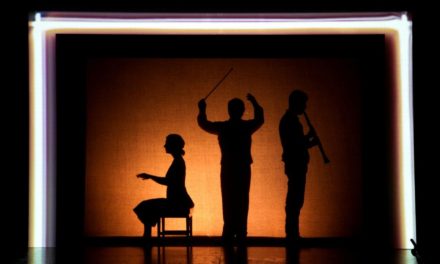

Ronja, córka zbójnika [En: Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter], based on the novel by Astrid Lindgren, translated by Anna Węgleńska. Foto credits: Natalia Kabanow. Teatr Powszechny Warsaw.

Apart from the credibility of the environment, the plot is also highly fused with magic, a nocturnal, dark, even hellish one. Ronja (Klara Bielawka) and her rival-family friend (Andrzej Kłak) are no longer images of pure-hearted children, adopting characteristics of their background, with hints of naughtiness and rebellion, and (God forbid!) moments of standing up against their parents. This detaches the happy-end from anything Deux ex machina-like and from the importance that is frequently given to magic and the Fantastic in children’s productions – they become a natural, realistic depiction of kids approaching their teenage years and, thus, give a bit of hope regarding young hearts’ capacity of actually making a change.

Although a risky directorial decision, having both child-characters have the same actress (Aleksandra Bożek) play their mothers turned out to be in the ultimate favor of the whole production – amusing both audience groups. If on the one hand we have a strong female voice in a world of men, opinionated and listened to, on the other side of the story, Birk’s mother is but a mere, yet hilarious caricature of hysteria, anger, and lack of power, providing the whole construction with a balance in terms of relatable imagery of mother figures.

Ronja, córka zbójnika [En: Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter], based on the novel by Astrid Lindgren, translated by Anna Węgleńska. Foto credits: Natalia Kabanow. Teatr Powszechny Warsaw.

Overall, Ronja, córka zbójnika [En: Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter], does not… play. The little spectators are not spared of clearly declared conventions, imaginative, yet highly cognitive-demanding sets, emotional tribulations, and, aligned with the necessities of young-audience productions, educative scenarios and lessons. Without having an overwhelmingly-moralizing tint, the main character’s coming of age story escapes the den of thieves and multiplies inside the hall, in each Ronja or Birk, regardless of age.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Teodora Medeleanu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.