The play My Father – His Exalted Highness was a nuanced depiction of the concerns of a ruler on the cusp of history.

For about 75 minutes, the stage at Ravindra Bharathi became the Nazir Bagh Palace of King Koti, as three characters gave us a peek into the history that has now passed into the annals of time, probably misunderstood and misrepresented. My Father – His Exalted Highness is, at the surface, a play dedicated to the last Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan (enacted by Dr. Mohan Agashe), taking a kaleidoscopic look through one of the most turbulent periods in the history of the erstwhile princely state of Hyderabad.

Penned by Noor Baig, who also plays the important character of Shehzadi Pasha (the spinster daughter of the Nizam), the play is a prism — an inspection of facts and myths, rumors and allegations that have decorated and tarnished the reputation of the last Nizam. On an evening of all-round brilliance, Noor’s playwriting sparkles through her brilliant dissection of Mir Osman Ali, an able administrator, a secular ruler, and a magnanimous philanthropist, but at times, a father who hasn’t really been fair to his daughter.

The opening play of Qadir Ali Baig Theatre Foundation’s fest starts with a bemoaning Shehzadi Pasha, missing her dad (who passed away in 1967 when she is 57) and yet, wondering who would be his heir, and who really deserves to be — alluding to the fact that it was she who had spent what would feel like eons with the Nizam. Mohammad Ali Baig plays Raja Rao, the Nizam’s loyal Prime Minister, an understated but effective character, used to give voice to the Nizam’s musings, while also breaking the fourth wall.

The Nizam’s idiosyncrasies emerge through his disappointment at his portrayal as the Time’s Person of the Year, something his daughter is elated about. What glory lay in being born in a wealthy family when his administration and his reforms were barely addressed in the piece about him, the Nizam laments. The quagmire in which Hyderabad finds itself during the Partition, the Nizam’s vacillations in deciding which side to choose and eventually acceding to the Union of India, is another episode that’s highlighted. And this is where the writing oozes maturity, yet again, for the oft-narrated tale of Hyderabad’s possible leaning towards Pakistan is relegated to the bin (a funny moment when the Nizam narrates to his daughter how he decided to not join Pakistan because of the way Jinnah sat cross-legged, pipe in his mouth, as he waited for the Nizam). The angle brought out instead, in the Nizam’s own disappointed tone, was the perceived betrayal by the Britishers. Despite the Asaf Jahi dynasty’s British loyalism for over seven generations, and their hefty donations of money to the Allied Forces during the Great war, the best King George could do was ‘pray’ for Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali bewails in the play. That’s a dimension seldom addressed when the Nizam’s proclivities and initial reluctance to join the Indian Union are discussed.

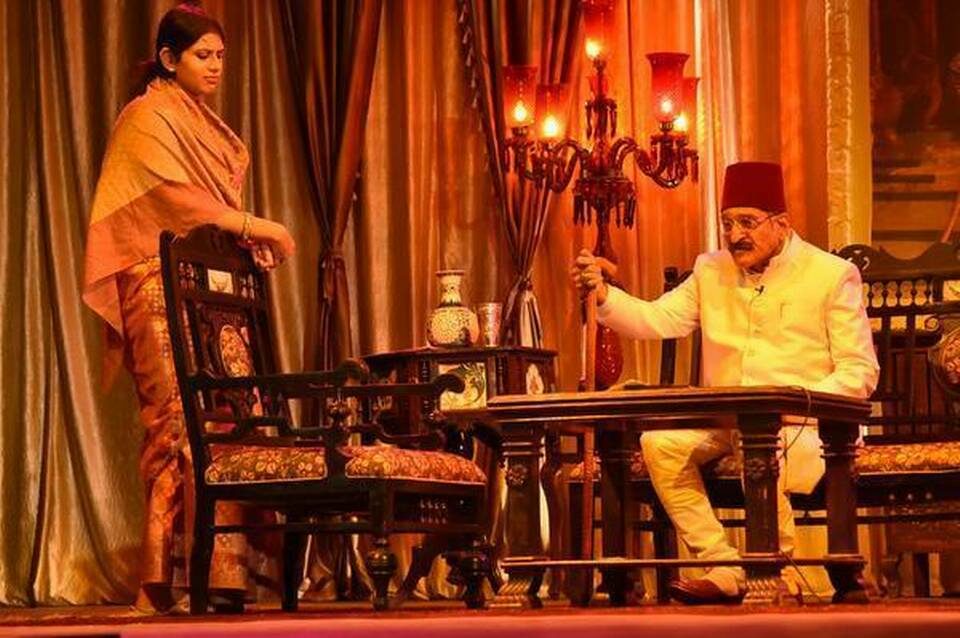

Mohan Agashe and Mohd. Ali Baig in a scene from the play. Photo Credit: By arrangement

A dense undertone of the play, was Noor’s Shehzadi Pasha, perpetually at the fringes of Mir Osman Ali’s life without the acknowledgment that she belongs, ‘always in his shadows’, despite learning so much from him, and how she yearns for her father’s approval. The audience is enthralled with the clever mix of dialogues, monologues, soliloquies and fourth wall narrations. Noor’s depiction of Shehzadi Pashawas full of bitter-sweet verve.

Mohammad Ali Baig brought out the dignity that befits a Prime Minister, loyalist without being ingratiating.

Mohan Agashe brought out the eccentric genius of the Nizam beautifully, modulating his voice and body language vividly, from a sprightly Nizam to a heartbroken older man. The play wouldn’t be what it was without the actor’s seasoned, nuanced, and meticulous portrayal of the Nizam.

The only downside was the slow transmogrification from being Shehzadi Pasha’s story to that of the Nizam. To explore more of what she thought and what happened of her after the Nizam’s demise would have been a wonderful tribute to women who were probably able but never treated as equals.

This article was originally posted at The Hindu and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Krishna Sripada.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.