Draupadi was performed by Kalakshetra, Imphal, at Gyan Mancha, Kolkata, on 30 August 2017. Midway through the performance, I felt distracted. A stifling sense of fatality had gripped my mind. I had begun wondering at that moment whether it is at all possible to see or discuss repeat performances of a theatrical production without invoking a comparative paradigm. Deep down, I was still aware of how the immediate social-political, spatial and other performative contexts frame our viewing of each performance. I knew how each individual performance is not merely a repetition of earlier ones but a new singularity produced out of its very unique material conditions. But at that very moment, it seemed impossible for me to think of the Draupadi performance I was witnessing as anything other than a subservient shadow of previous performances. It seemed as if I was destined to remember this performance only as an inferior version of a legendary production. But I did not know then that the final twist in the tale was yet to happen.

Draupadi had already been staged in Kolkata multiple times; I myself had seen it twice. This performance was organized by Pratyay Gender Trust, a sexuality rights initiative started in 1997–98 by members of Kolkata’s kothi [1], hijra [2], and other gender-non-conforming/transgender women. The performance was this year’s event for the annual Rituparna Ghosh Memorial Lecture organized by the trust. For an audience well versed in the history of contemporary Indian theatre practice, it indeed seems impossible to witness Kalakshetra’s Draupadi without being overwhelmed by the baggage of certain political and aesthetic anticipation. Neither Heisnam Kanhailal (1941–2016), nor his wife, the revered actress Sabitri Heisnam (1946–) or the theatre group that Kanhailal had founded in Imphal, Manipur, almost half a century ago – Kalakshetra (est. 1969) – need any new introduction to theatre lovers in India, or now, perhaps, even across the world. Kanhailal, who passed away last year, leaving a gaping void in Indian theatre, has, through a sincere and relentless quest with his group in Imphal, Manipur, developed a singular political and aesthetic vision, whose legacy has already inspired theatre workers around India and promises to continue to do so in future.

The decaying and suffocating socio-political reality of Manipur has been integral to Kanhailal’s theatre. Kanhailal’s productions, like Pebet (1975), Memoirs of Africa (1986) and Draupadi (2000), have critically and succinctly dissected both the historic religious indoctrination and the contemporary systematic military repression of the land of Manipur and its people under AFSPA [3]. However, if the socio-political reality of Manipur is where Kanhailal has situated his theatre, his minimalist aesthetics is drawn from an intense focus on the actor’s body inherited from traditional performance forms and honed through regular exercises in close proximity with nature. His symbolic dramaturgy, emphasizing the mythical and the ritualistic, attempts to bypass the logocentric universe of dramatic theatre with its excessive reliance on spectacle and the conventions of the proscenium. What sets Kanhailal’s productions apart, however, is that despite being deeply rooted in the history; contemporary socio-political reality; and oral, literary and embodied forms of cultural practices of Manipur, they also anticipate in them a universal theatrical language transcending their immediate contexts of production. In spite of being timely or even clairvoyant in their political intervention, Kanhailal’s productions strive to create timeless archetypes of figures and situations which manage to produce affect beyond linguistic and cultural barriers. Some of his productions, like Draupadi itself, have been better received and appreciated outside Manipur, to begin with. Within this uncanny conjunction of the timely and timeless lies the beauty of Kanhailal’s theatre.

Among the repertoire of Kanhailal’s productions, Draupadi, adapted from renowned Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi’s noted short story of the same name, is one of the most widely known and discussed. This is not only because of the pressing political concerns it addresses and the radical manner in which it does so, but also because of the controversies it generated and, most important, its eerie prophetic quality, which was revealed in a scintillating turn of events preceding its staging. After Draupadi premiered in Imphal on April 14, 2000, the production had to be stopped after only two shows under tremendous backlash from across Manipuri society. Critics, including feminist groups, as well as the general public, felt offended by and objected to the nude scene at the end of the play, where Sabitri, playing the character of Dopdi Mejhen in the performance, bares herself before the army personnel raping her, in an intrepid act of defiance. Kanhailal was pronounced as possessing a depraved and perverted sensibility for conceiving the scene, and Sabitri was called a shameless and notorious woman for baring her body on stage. A select group of male intellectuals, however, spoke in favor of the production, declaring it a valid mode of protest against the Indian Army’s repeated sexual assaults against Manipuri women. The controversy raged in the local media for the next four months.

In a serendipitous turn of events, four years later, on July 15, 2004, twelve Manipuri women staged a nude protest in front of the Kangla Fort, Imphal, against the rape and extra-judicial killing of Thangjam Manorama by the Indian Army on July 11, 2004. Their indignant cries of “Indian Army rape us . . . we all are Manorama’s mothers” and “Kill us, rape us, flesh us [4]” not only was an immediate reaction to Manorama’s killing but also gave vent to the Manipuri community’s hitherto suppressed but growing anger toward its systematic military oppression by the Indian state under AFSPA. As Trina Nileena Banerjee has pointed out in her own research on the Draupadi performance [5], the twelve mothers were unaware of Sabitri’s act in the play and were acting of their own accord. Kanhailal, in an act of sheer clairvoyance, had anticipated in Draupadi the events that were to transpire four years after the performance was first staged. Moreover, such a mode of protest perhaps was possible only in Manipur, with its long history of women’s active participation in the public sphere and women’s collective revolt against social injustices. That Kanhailal could anticipate it shows his deep attachment to an adept understanding of Manipuri people and their culture.

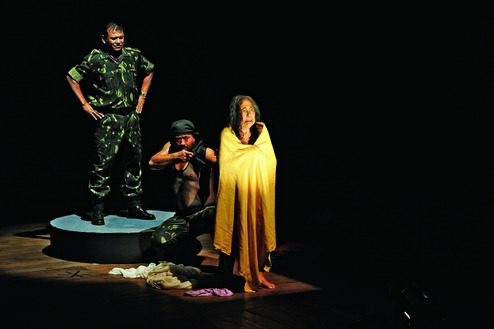

The Draupadi narrative and the performance in many ways embody the spirit of resistance which pervades Kalakshetra’s theatre practice. The challenge to sustain an artistic and cultural practice in the decaying social milieu of Manipur, the struggle to maintain the dignity of human life in the face of inhuman treatment and brutal torture, resonates in Dopdi Mejhen’s refusal to abandon her self-esteem even under utter humiliation. In Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi, authored in 1976 and translated into English by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in 1981, situated during the Naxalbari movement in 1970s Bengal, Dopdi Mejhen, a tribal woman, who has actively worked for the movement and has eluded capture by the military along with her partner, Dulan, is ultimately apprehended after Dulan is killed. Captain Arjan Singh, the Senanayak (commander) in charge, asks the military personnel to “make her” and “do the needful,” following which Dopdi is gang-raped. In the final moments of the story, Dopdi is taken to meet Arjan Singh. In an unexpected turning of the tables, she refuses to wear her clothes and confronts Arjan Singh with her mutilated naked body, asking, “you can strip me, but can you clothe me again? Are you a man?” The Senanayak is unsettled by this sudden and unforeseen assertion. Kanhailal, in his own characteristic method, breaks down this narrative and reconstructs it in his signature dramaturgical style, consisting of a series of meticulously arranged images, movements, and sounds, all culminating in the final act of confrontation where Sabitri as Dopdi bares herself on stage.

Returning to the performance in a discussion, it seemed to undermine the memory of previous viewings. The stage was set perfectly for another flawless act from the Kalakshetra group. The occasion was befitting, the intimate ambiance of the auditorium at Gyan Mancha was perfectly suited for the performance, the hall already packed with an audience eager to witness Draupadi and Sabitri once more. But as the performance began and went on, I realized that something was amiss. Though this was the third time I was witnessing the performance, it was not its predictability which was lessening the impact. Rather, it was the jerky and inconsistent quality of the performance itself on the particular evening which seemed distracting. There were subtle errors in coordination, transfer of rhythm, timing, which may have been missed by a first-time viewer, but to me, each of these slips was glaring.

At the same time, I was also realizing once again the painstaking detailing, the subtle craft, the discipline, the economy of expressions which work together to make Kanhailal’s productions what they are. I realized that what appears to be so easy to the eye is, in fact, a complicated artifice, whose every element is equally crucial in its proportionate presence. The effect which seems to generate naturally is produced through a series of pre-planned and perfectly executed actions, any deviation from which puts the entire performance in jeopardy. What was also made evident is that, unlike a film-screening, each performance of the production is a new event, a new work altogether. It is a new challenge under new conditions, for which the performers must undergo a range of preparatory activities; even after these are followed meticulously, the performance might not work on a particular day owing to a gamut of different contingent factors. The very next day, I would learn from a close friend, who was part of the performance that day, how some of the performers were farmers and had returned from their farming work only two days before, which left them little time for preparations.

While the flaws kept creeping in, the onus once again fell on the ever-resolute and assured Sabitri to salvage the performance, to give it the direction and calm it so desperately needed. It was not going to be easy. As the performance entered its crucial final sequence, Sabitri had to dig deep into her energy resources to maintain the required intensity of the scene. However, by the time the rape sequence was over and she had begun chanting “ma ho” repeatedly, I felt the whole auditorium brimming with emotion, as I have witnessed so many times before with Kalakshetra’s performances and especially Draupadi. As the performance ended and the lights came up, I could see that the audience was visibly moved, and many were even crying. As Sabitri entered the stage again with her troupe for the curtain call, she too was in tears, utterly exhausted and dejected. The almost herculean struggle had left her drained of all energy, and to add to it she did not have Kanhailal this time beside her to share her feelings with. It was veteran theatre critic Samik Bandyopadhyay [6], present in the audience, who when called to the stage to congratulate Sabitri and the group lovingly embraced her in a heart-warming and empathetic gesture. He also shared an enriching anecdote about how in the course of a discussion with Kanhailal he had suggested to him the text of Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi for adaptation.

As I was leaving the auditorium, making my way through the crowd, I was warming up to the knowledge that though this might not have been the best Kalakshetra or Draupadi performance I had seen, it was still going to be a Draupadi performance I would remember for a long time, albeit for entirely different reasons. I would remember it for the formidable actor who stood unflinchingly between coherence and obfuscation, between art and banality: the actor. The actor who resisted not through the role she played but by her very embodied presence. I realized that it is perhaps in this manner that every performance, even if a repeated one, registers with us as a new singularity, uniquely inflected by its own time, and each time we are left with a new experience to share, a new story to tell.

Notes

- A kothi, in the culture of the Indian subcontinent, is an effeminate man or boy who takes on a female gender role in same-sex relationships. Kothis differ from hijras, as they do not live in the kind of intentional communities that hijras usually live in.

- In South Asia, a hijra is a transgender individual who was assigned male at birth. Many hijras live in well-defined and organized all-hijra communities, led by a guru. These communities have sustained themselves over generations by “adopting” boys who are in abject poverty, are rejected by, or flee, their family of origin. Many work as sex workers to survive.

- “The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Acts (AFSPA) are Acts of the Parliament of India that grant special powers to the Indian Armed Forces in what each act terms ‘disturbed areas’. . . . The acts have received severe criticism from several sections for alleged concerns about human rights violations in the regions of [their] enforcement” This controversial act has been operative in Manipur since 1958 and remains in place today.

- “Flesh us” was an expression used by the women protesting the atrocities of the Indian Army. To “flesh us” would mean to “skin us,” to “consume/abuse our flesh.”

- See Trina Nileena Banerjee’s essay “Kanhailal’s Draupadi: Resilience at the Edge of Reason”, in Theatre Of The Earth: Heisnam Kanhailal (Kolkata: Seagull, 2016), 153–65.

- Samik Bandyopadhyay (1940–) is a Kolkata-based critic of Indian art, theatre and film and a well-known book editor. In his long career, he has been associated with multiple academic institutions and participated on various important committees and has enriched the Indian cultural scene, especially theatre, in varied roles as a critic, historian, researcher, teacher, translator, editor, and administrator.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rajdeep Konar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.