Recently, Delhi hosted the dramatic production Ram ki Shakti Puja, by the Banaras-based theatre group Roopvani. The performance was staged at Kamani auditorium’s Meghdoot Theatre on May 27, 2017. The title, translated as “Ram’s worship of Shakti,” is taken from the epic poem “Ram ki Shakti Puja,” composed by the iconic modern Hindi poet Suryakant Tripathi “Nirala.” “Ram ki shakti Puja” is a modern Hindi epic poem that explores the theme of spiritual and moral struggle in the face of injustice. Based on an episode in the life of the deity King Ram who was battling his opponent Ravana, who embodies unrighteousness and pride (from the Sanskrit epic Ramayana), this poem delves into the spiritual crisis of Ram in the battlefield. As Ram realizes the presence of Shakti, the goddess of vitality and power, fighting on Ravana’s behalf, his morale becomes low. Ram’s situation is every person’s situation who finds power supporting the unjust at some point in life. Ram is presented as a committed leader and an unwavering devotee in the poem. The conclusion establishes that it is only through unyielding moral and spiritual strength that one can stand in the face of injustice (adharma). The battleground is not external, but within one’s self, where a human being has to counter her opponents in order to stay committed to the path of truth and justice.

The action opens in media res, at the battlefront, where Ram and Ravana are engaged in the last leg of their battle. In the final hour, Ram, an icon of justice and truth, finds his morale waning. The primary reason for this is that he witnesses the Goddess Shakti’s support of Ravana’s army. As director, Vyomesh Shukla highlighted in his short introductory speech contextualizing the drama, the leitmotif of the piece is the sentence from Nirala’s poem “anyaya jidhar, hai udhar shakti” (“where there is injustice, lies power”). This statement sharpens the moral dilemma that power easily sways towards the unjust. Observing this, the lord who symbolizes justice and truth also suffers from apprehension and doubt. Ram has been characterized as a man, a king, a lover, and a warrior, which makes the poignancy of his realization sharp and accessible to audiences. The intervention by the wise Jamvant, who counsels Ram to beat Ravana’s devotion to Shakti by demonstrating his unwavering worship of her highlights the themes of surrender and devotion. When Shakti tries Ram by foiling his offering of the 108th blue lotus, Ram doesn’t flinch even for an instant, deciding to offer his own eye instead.

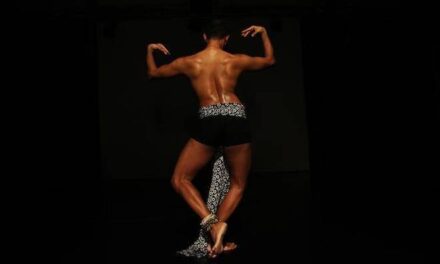

The performance adapted classical music and the dance traditions of Hindustani music (Banaras gharana), chhau, kathak and Bharatnatyam. The martial rhythms of chhau and the lyrical meter of Bharatnatyam were juxtaposed in ways that made the transition between the rasas smooth. From Ram’s painful remembrance of Sita, to Hanuman’s anger, the dance forms gave full justice to the bhavas and mudras (sentiments and postures) of karuna, shringara, raudra and virr rasas.

The rasa that was outstanding in this performance was vatsalya rasa, of love between a parent and child. At two points in the play, this emotion was evoked, leading to a turn of events in the plot. The first instance was during the anger of Hanuman, who was overcome with self-destructive rage. At this point, his mother appeared to pacify him in order to protect him from himself. The transition from raudra to vatsalya rasa happened with the entry of a child actor who briefly played the role of Hanuman. During this time, the adult actor in the role of Hanuman remained on stage, with minimal gestures, while the child’s movement dominated. This transition was staged to show Hanuman’s rage giving way to composure, with the final freeze as the child Hanuman atop the shoulders of his mother.

The second evocation of vatsalya occurred towards the end, when Ram decided to offer his eye to demonstrate his worship of the goddess. At this point the mother goddess, who is the universal mother of mankind, is filled with love for her child, Ram, who is willing to do the unthinkable to prove his devotion. At the dramatic posture where Ram held out a sword to pierce his eye, Shakti held his gesture and offered the 108th flower herself. She then placed vermilion on his forehead to symbolically declare his imminent victory.

A remarkable feature of this production was that the roles of Ram and Lakshman were played by women. Apart from subverting the tradition of Ramlila, where female parts are also played by male actors, this had an important sobering effect on the martial tempo of the plot. This is highly important in the present time when the martial cries of Ram’s army have become slogans inciting violence between people. The lyrical movements and the erotic (shringara) dalliance between Ram and Sita were striking and beautiful. The expressive eyes and face of the actor playing Ram highlighted the chasm between shringara and vira as the audience witnesses the transition from vira (valour) to karuna (pathetic) to shringara (erotic). The remembrance of Sita and their times spent together, when juxtaposed in the war zone, drew attention to another enduring feature of Ram’s persona: his dedication to the cause, but his inherent abhorrence of the idea of violence, something that war necessitates and perpetrates.

Theatrical adaptations of poems are not easy because the lyricism and metaphorical dimensions of language are not easy to adapt to the stage. This challenge was overcome with the use of song lyrics instead of dialogue. The lyrics used lines from the poem in many places, thus enabling a smooth flow of imagery and action. This play was earlier performed in Varanasi, and its tropes and structures have been improvised, revised and revisited for years now. This production showed how the classical can always be re-read and re-presented in contemporary contexts.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Namrata Chaturvedi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.