On September 21, 1972, then President Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law via Presidential Proclamation Number 1081. The proclamation was supposedly issued to suppress the rise of communism in the archipelago. But since its declaration, an estimated 70,000 individuals were imprisoned, 34,000 tortured and 3,240 killed.

Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus paving the way for many human rights violations. Marcos lifted martial law on 17 January 1981. Finally, a peaceful revolution dubbed as the People Power overthrew the dictator on 22 – 25 February 1986.

On May 9, 2016, the Filipino people elected then mayor of Davao City Rodrigo Roa Duterte as the 16th president of the Philippines. Duterte is infamous for the transformation of Davao City from a lawless city into a city of order. Duterte is a self-proclaimed Marcos loyalist. His father was a member of Marco’s cabinet. Duterte also believed that illegal drugs are the reasons for the crimes in the country. As such, he announced a nationwide “war-on-drugs.” Blatantly, he also proclaimed on live television to shoot suspected drug dealers if people wanted to help the government.

Since his landslide victory in 2016, the police, military and even ordinary people (popularly labeled as riders-in-tandem) killed an estimated 13,000 individuals due to Duterte’s war-on-drugs. Latest casualties: three teenagers – a grade 11 student, a sophomore from the University of the Philippines and a 15-year old boy.

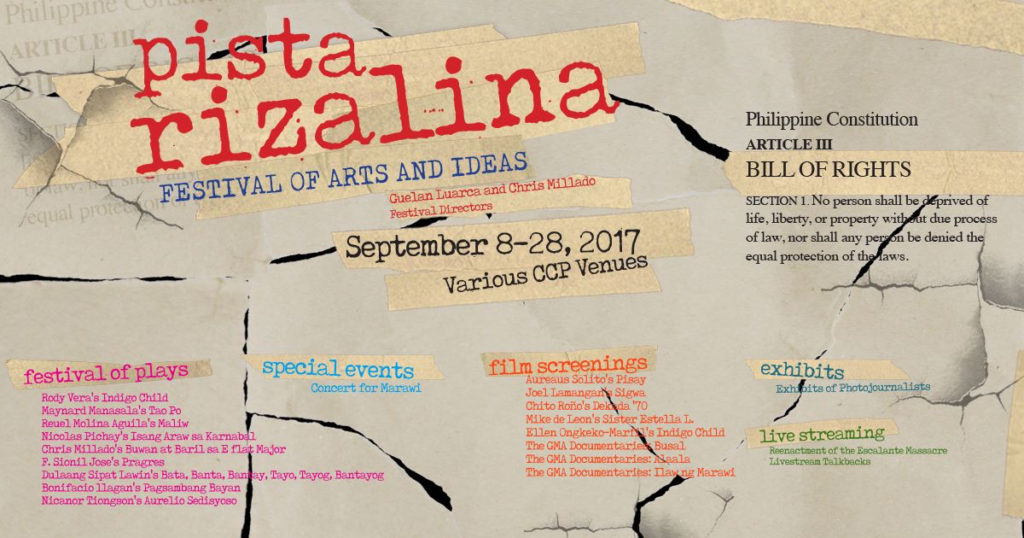

The current state of the nation motivated many artists to evaluate and address the most urgent concerns of the nation especially issues on human rights. For instance, the CCP through its Vice President Chris Millado and a young playwright-director from the Ateneo de Manila University Guelan Luarca staged Pista Rizalina. The festival was dubbed as a gathering of arts and ideas, a month-long festivity of theatre, films, and lectures with the Philippine Bill of Rights as the centerpiece.

The Festival Poster (Courtesy of Cultural Center of the Philippines Official Facebook Page)

CCP President Aresnio J. Lizaso and CCP Vice President and Artistic Director Chris Millado write in the festival program that Pista Rizalina “engages various art forms to start conversations on topics that are relevant to the times. The festival brings together artists and thought leaders to stimulate public discourses in the most creative and engaging way.” For Millado, it seems that the entire nation is experiencing a historical amnesia. Millado, who witnessed the dark days of the Marcos dictatorship, feels “it is particularly imperative that millennials and the young generation do not fall victim to historical revisionism” as cited in an online report by columnist Totel V. De Jesus.

The festival was named after Rizalina Ilagan, a student-leader, and activist from the University of the Philippines Los Baños who was arrested by the military in July 1977. Rizalina, together with ten other students were the first of the many Filipinos who disappeared – abducted by the military, and are believed to have suffered tortures between 1977 and 1981. To this day, these desaparecidos (the disappeared) have not been found.

The festival is dedicated to the memory of Rizalina Ilagan and other victims of martial law. Staged from September 8-18 2017, the festival featured six one-act plays and a full-length play at the Tanghalang Huseng Batute (CCP Studio Theater), two full-length productions at the Tanghalang Aurelio Tolentino (CCP Little Theater), six feature-films screened at the Tanghalang Manuel Conde (CCP Dream Theater) and three documentary films also screened at the CCP Dream Theater.

Curated by Millado and Luarca, participating artists include former Artistic Director of Tanghalang Pilipino Herbie Go, Sipat Lawin Ensemble’s Artistic Director J.K. Anicoche, Kolab Company’s Maria Teresa Jamias, playwrights Rody Vera, Maynard Manansala, Reuel Aguila and Nicolas Pichay, UP College of Mass Communication Professor Emeritus Nicanor G. Tiongson, Visual Artists Toym Imao and Leeroy New, television and stage director Andoy Ranay, UP professor and director José Estrella, director Ed Lacson, Jr., Tag-Ani Performing Society’s Bonifacio Ilagan, Rizalina’s younger brother to name a few.

One-Act Plays at the Studio Theatre

The festival opened on September 8, 3 PM, at the CCP Studio Theatre with two plays by the graduating theatre majors of the Philippine High School for the Arts (PHSA). The first play was Herbie Go’s Pragres – the story of a government employee from the province based on a short story Progress by F. Sionil Jose, a National Artist for Literature. The second play Bata, Banta, Bantay, Tayo, Tayog, Bantayog (Child, Warning, Guard, Poised, Monument) is a devised piece by Sipat Lawin Ensemble based on research and data on human rights violations during Martial Law, personal experiences of political detainees and families of the disappeared and the Tasaday Hoax.

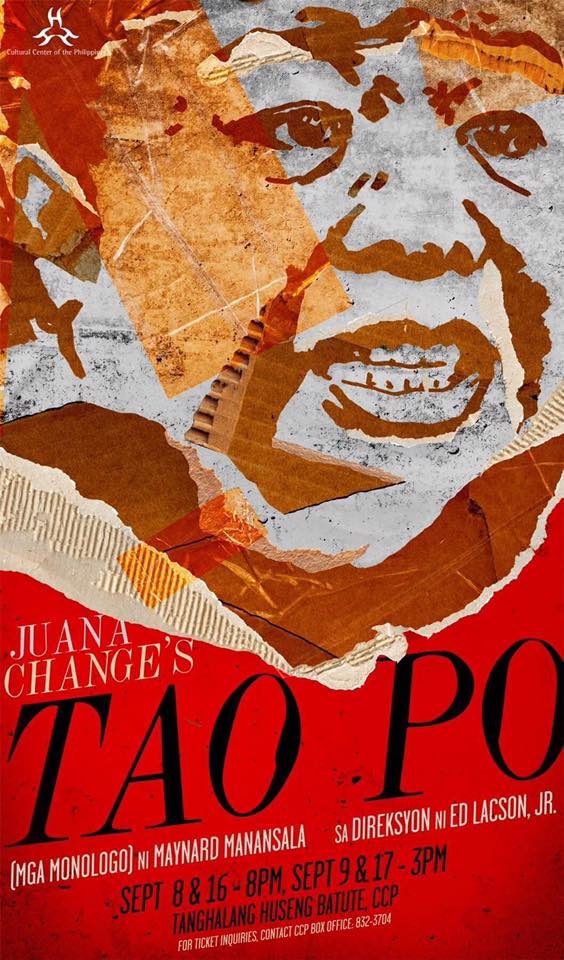

At 8 pm, Rody Vera’s Indigo Child (dir. José Estrella) which debuted in Never Again Festival at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani in February 2016 and Maynard Manansala’s Tao Po (Anybody’s Home?, dir. Ed Lacson, Jr.) collectively called SET A were staged. In this set, audience members are presented with a contrasting image of human rights violation: the former, during the Marcos regime and the latter, an exposition of the human rights violations encountered under the present administration. This set was also performed on September 9 and 17 at 3 pm, and on September 16 at 8 pm.

The poster of Maynard Manansala’s Tao Po (Photo from the Official Facebook Page of the Cultural Center of the Philippines)

In Indigo Child, Vera brings us to the inner psyche of a woman Felisa (performed by Skyzx Labastilla), an activist during the Marcos regime and was tortured by electricity during the same era. Felissa is currently undergoing shock therapy as a treatment for her bipolar disorder due to multiple traumas. Helping and accompanying her in the hospital is her son Jerome (performed by Rafael Tibayan) – who also doubles as the play’s narrator. The shock therapy brings back the horrors she encountered with a commander named Kidlat, who during the traumatic experience she went through as an activist, raped her. Toward the end of the play, it is revealed that Commander Kidlat is the father of Jerome; hence an indigo child.

In contrast, Maynard Manansala’s Tao Po is a series of four monologues based on the current human rights violations supposedly committed by the current administration: the Extra Judicial Killings (EJK) as a result of the government’s war-on-drugs. The play is a product of a series of interviews and field works documented by playwright Manansala, producer and actor Mae Paner (popularly known as Juana Change), playwright Rody Vera (production dramaturg in this play), and filmmaker Moira Lang (formerly Raymond Lee).

On September 9, Reuel Aguila’s Maliw (Enduring) and Nicolas Pichay’s Isang Araw Sa Karnabal (One Day In The Carnival) both directed by Cris Millado were staged. Collectively called Set B for the festival, both plays pay tribute to the desaparecidos or the disappeared. Originally directed by Edna Vida Froilan for the 5th Virgin Labfest of the CCP, Tanghalang Pilipino and the Writer’s Bloc in 2009, Maliw follows the story of a former activists couple whose eldest daughter disappeared due to her strong advocacies in social activism.

Isang Araw Sa Karnabal is also a restaging. It was also part of Virgin Labfest 5 and was also restaged in 2012 alongside Maliw. Originally performed by Skyzx Labistilla and Paolo O’Hara, this restaging welcomes Sheenley Gener and Yul Servo as the estranged activist-lovers whose loved ones went missing during the time of Martial Law. At present, they decide to meet again and try to mend broken ties. The play is a poignant testament to how the Martial Law destroyed homes and relationships.

“Buwan at Baril in Eb Major”

Cris Millado’s Buwan At Baril In Eb Major (Moon And Gun In Eb Major) had a restaging at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Auditorium in October 2016. For the festival, Millado’s political play stepped foot at the CCP Studio Theatre on September 15.

Written in 1984 as a commissioned play by the Philippine Educational Theatre Association, the play revolves around the lives of eight individuals: a farmer, an urban worker, a priest, a barrio woman, a socialite, a wife of a New People’s Army leader, a student activist and a police whose everyday lives criss-cross as they search for truth, justice, and inner-peace.

Television and theatre actor JC Santos (standing) with movie and theatre actor Angeli Bayani (seated) in a scene from Buwan At Baril In Eb Major during its restaging at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Auditorium in October 2016, Quezon City. (Photo: Vladimir Bunoan)

These characters symbolize the sectors involved in the anti-Marcos struggle. The structure of the play is inspired by the movements of a symphony or acts in an opera (hence, the E-flat major in the title of the play). With this, each character has a soliloquy or a monologue while background music is reminiscent of opera tunes mimicking “sadness” as perceived by the E-flat mode in musical composition.

Originally directed by Apolonio Chua, the 2017 staging is directed by theatre turned television and movie director Andoy Ranay. Included in the cast are television, movie and theatre veterans (Cherrie Pie Picache, Jackie Lou Blanco, Paolo O’Hara, Angeli Bayani, Danilo Mandia, JC Santos, among others). These individuals explicitly proclaim their disgust against historical revisionism and human rights violations via the EJKs.

Film Screenings

On September 20, 1985, a group of sugar workers, farmers, fishermen, students and church people staged a public protest in the town center of Escalante City in the island of Negros. The crowd protested against the creation of Negros del Norte. Negrenses (locals of the Negros Island) believed that the creation of Negros del Norte was a maneuvering of Marcos’ cronies to consolidate more power in the Northernmost region of the island. That time, the Northern Negros is known for its abundant sugar plantation. Mid-afternoon, on the 20th, a fire truck arrived and began bombarding the human barricade with high-pressure water. Paramilitary started throwing tear gas but was not able to disperse the crowd. Some protesters threw back the canister into the paramilitary forces who started open-fire. Thirty were wounded. Twenty protesters were killed.

Reenactment of the Escalante Massacre (Photo taken from the Concerned Artist of the Philippines Official Facebook Page)

Annually, the Negrense community of Escalante City commemorates the massacre through a reenactment. Led by the Negros Theatre League, the reenactment was live-streamed for the first time at the CCP Dream Theater.

In addition to the live-streaming, documentaries and feature films about Martial Law were also screened at the CCP Dream Theatre. The CCP collaborated with the News and Public Affairs of GMA 7, a popular television network with the documentaries featured in the festival. Documentaries featured were Howie Severino’s documentary about poor families of the casualties of Oplan Tokhang billed as Busal (Gag); Adolfo Alix, Jr.’s 2-hour long documentary on the life story of Bonifacio Ilagan titled Alaala: A Martial Law Special (Memory); and the Howie Severino’s Ilaw Ng Marawi (Light Of Marawi), a documentary on the struggle of the Maranaos on the current war against terrorism.

For the feature films, the following were screened: Aureus Solito’s Pisay (2007, popular name attributed to the Philippine Science High School), about a group of 8 future scientists affected by the Martial Law; Joel Lamangan’s Sigwa (2010, Storm), about the first quarter storm movement of young activists against Marcos in the early 1970s; Chito Roño’s Dekada ’70 ( 2002, The Decade Of The 1970s), based on the novel of the same title by Lualhati Bautista depicting the struggle of a mother during the peak of the Martial of Law; and Mike de Leon’s Sister Stella L (1984) about the struggle of a nun against injustices and oppressions experienced by factory workers in the nearby convent where she stays. The staged film version of Rody Vera’s Indigo Child filmed by Ellen Ongkeko-Marfil was also screened during the festival.

Full-Length Plays

Two full-length productions were staged at the 421-seat CCP Little Theatre: the world premiere of Nicanor G. Tiongson’s Aurelio Sedisyoso (The Seditious Aurelio) and the restaging of Bonifacio Ilagan’s Pagsambang Bayan (The Nation’s Ecumenical Service) originally staged in 1977, considered the first play that directly criticized Marcos and his martial law.

Part of Tanghalang Pilipino’s 2017 – 2018 theatre season and opened on September 8, Aurelio Sedisyoso is based on the life and works of Aurelio Tolentino. Tolentino was a playwright and a revolutionist during the turn of the 20th century. His plays led him and his company to imprisonment due to sedition. Directed by Chris Millado, the life story of Tolentino was devised into a rock-musical.

Tolentino belongs to a generation of artists who were bold and courageous to expose horrors of colonization via the traditional form sarsuwela, introduced by the Spaniards in 1878. Tolentino was one of the first theatre-artists who used the sarsuwela into a revolutionary agend. These plays were labeled drama simbolico (symbolic drama) and tagged seditious by the Americans. American viewers would not recognize immediately that something nationalistic (therefore “subversive”) was being communicated to local audiences. For this reason, on November 4, 1901, the American government passed Act No. 291 or the Sedition Act, disallowing any form of assemblies that advocated independence.

The staging of Aurelio Sedisyoso reminds the audience about the continued oppression that the nation is experiencing. Through the devices popularized by the sarsuwela, the rock-musical provides glimpses of oppression experienced today via symbols found in the set (i.e. a head covered in packaging tape as a reference to the current EJKs) designed and executed by installation artist and sculptor Toym Imao.

Closing the festival was Bonifacio Ilagan’s Pagsambang Bayan staged from September 22-24, 2017. Ilagan – the older brother of the honoree of this festival – wrote Pagsambang Bayan right after his release from prison. During the press conference for the festival at the CCP, Ilagan said that the Bible was the only book he and other detainees were allowed to read. This served as his impetus to write Pagsambang Bayan which he says, was structured like a real mass.

A scene from the 2017 staging of Bonifacio Ilagan’s Pagsambang Bayan (Photo: Courtesy of Juan Carlo Tarobal)

Inspired by the conventional Sunday services of different Christian churches, the members of the congregation of Pagsambang Bayan are the workers, peasants, indigenous peoples and even professionals. Following the tradition of dula-tula (poetry turned into dramatic texts) popularized by the UP Repertory Company during the martial law, the play revolves around a discussion of the condition of the nation. The congregation is invited to argue with the church leader who often quotes biblical passages to analogize the oppressive nature of the regime.

The 2017 staging presented allusions to martial law as it opened with images of the dictator being buried at the National Heroes’ Cemetery. Overall, the play invites the audience members to reflect the current conditions of the archipelago. In this staging, performers sing familiar tunes alluding to both Martial Law and Duterte’s administration: Bayan Ko (My Country), popularized during the 1986 People Power Revolution that overthrew the dictator and the church-song Pananagutan (We Are All Accountable), which invites the audience to remember “tayong lahat ay may pananagutan sa isa’t isa” (we have responsibility to take care of each other).

Generally, this month-long festival juxtaposed three eras: the 1896 revolution, Marcos regime and the current administration. The objective is to proclaim that as long as there are abusive regimes the theatre will always be speaking the truth and will always initiate an assembly.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sir Anril Pineda Tiatco.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.