“…Hamlet gives them cultural capital. It gives them ownership of something unique, not just material; it gives them insight, wisdom, pride, and status. These are riches they are permitted to own in an environment that is otherwise one of deprivation.” -Lorraine Moller

From Shakespeare to devised work, theatre has long been practiced by those who are incarcerated. Rob Pensalfini, author of Prison Shakespeare, cites that drama “in a prison context goes back in written record almost a century, or over two centuries if we include the Australian convict theatres of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (Jordan, 2002).” Whether it is for recreation or rehabilitation or a combination of both, the impact of theatre in prisons is a positive one and demands closer investigation.

The Theatre Times interviewed two theatre professors, Bruce A. Levitt of Cornell University and Lorraine Moller of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, about their experiences with and approach to facilitating theatre programs in prisons. Keep reading to get to know them and the personally impactful and theatrically relevant work coming from folks who are experiencing incarceration.

Bruce A. Levitt & The Phoenix Players Group

Bruce A. Levitt has been a professor in the Department of Theatre, Film, and Dance at Cornell University since 1986 and a facilitator for The Phoenix Players Theatre Group for eight years.

The Phoenix Players Group was founded by two incarcerated men, Michael Rhynes and Clifton Williamson, at Auburn Correctional Facility. Levitt adds that,

“In the words of the group’s founders, [PPTG] is a transformative theatre community, which utilizes theatre to reconnect incarcerated people to their full humanity.”

Since 2009, PPTG has held small, tight-knit workshops for two hours each Friday evening, with the aim of creating a space where imprisoned writers and performers can be witnessed, and where they can initiate a process of personal, cultural, and socio-political transformation.”

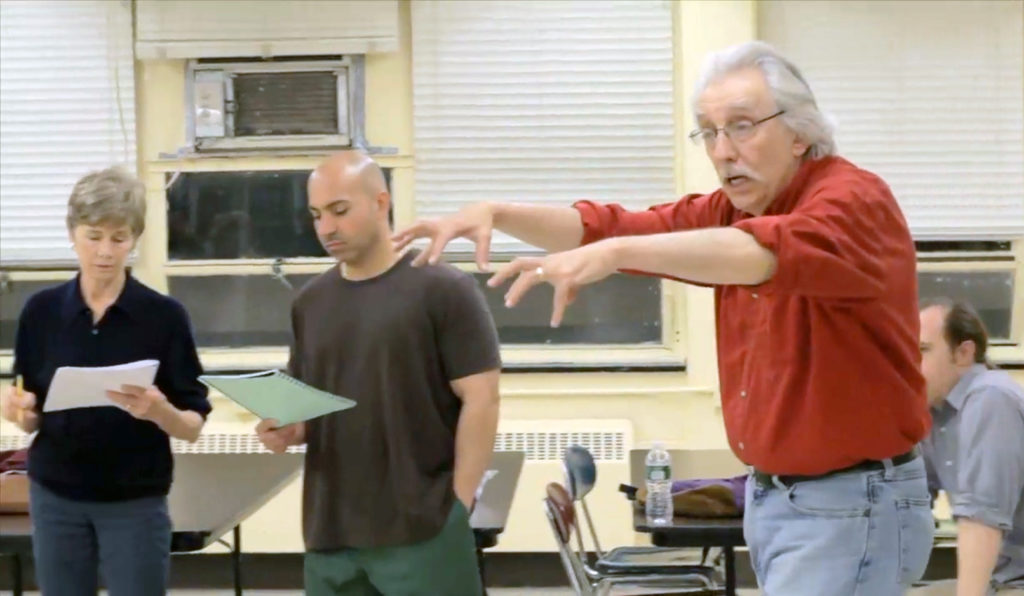

P.P.T.G. members and facilitators with students from the Prison Theater Class. Photo: Peter Carroll.

Lorraine Moller & Rehabilitation Through the Arts

Lorraine Moller is an Associate Professor in Communication & Theatre Arts at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. She has directed departmental productions as well as several productions at Sing Sing Correctional Facility and Bayview Correctional Facilities. A documentary covering the production of A Few Good Men, directed by Moller at Sing Sing is available to watch here. Moller is part of the original team of founders of Rehabilitation through the Arts (RTA), a program operating in five New York State Prisons.

“Rehabilitation Through the Arts…programs are offered year-round in a range of subjects including dance, fine art, and many aspects of theatre. Generally, two productions a year occur at most facilities. In 2001, the Department of Corrections began permitting a small civilian audience to attend productions and currently allows family of participating members to witness a production.”

Responses have been selected from a longer interview and have been edited for clarity and brevity. All photos and videos are from RTA and PPTG’s websites or Facebook pages.

How have two theatre professors gotten into the world of theatre for incarcerated people?

Levitt: My retired colleague, Stephen Cole, was asked to speak with Michael Rhynes and Clifton Williamson… They were very particular in what they were looking for in a civilian facilitator. Steve interviewed three times with the two incarcerated men before they would accept him. After working with the group for about 6 months, Michael Rhynes made it clear that in order for the transformation he was looking for to advance, it needed to be witnessed, hence performances became necessary. Steve brought in some plays but Michael was clear that he wanted the group to do its own material. Steve took me to lunch and discussed my getting involved since, besides directing everything from Shakespeare to new plays, I had also developed solo work with actors and collaborated on devised performances. I went to the PPTG workshop and observed twice…the six founding members quizzed me about what I could contribute. I asked them to bring in a list of events in their lives and the following week they read the lists…I had no idea of the story [or] context of the event in any of the men’s lives. I picked a few and staged them that very evening. After staging three of the “events” they told me I could stay. That was in 2010. I’ve been even there ever since.

Moller: …In 1996, the government pulled out the Pell Grants shutting down the college programs for the incarcerated. As part of a town-wide grassroots effort, a faith-based group invited community members to tour the Bedford Correctional Facility, so I attended.

The Superintendent gathered us in the visiting room and began to talk about the facility. Barely discernible from the civilians, thirty women quietly filed in during the lecture and took seats facing the audience on three sides. Gradually, I became aware that these well-groomed women wearing colorful tops, with stylish hair, and painted nails were wearing state-green pants… Each one spoke, giving her name and how many years she had served time at Bedford. It was shocking; women who looked 35 had been there 12 years, 15 years, some served even longer sentences.

It didn’t take long for me to volunteer and soon after I served as Co-Chair of the first community awareness/fundraising committee to bring back the college program…

…Working with these bright motivated inmates was empowering. Out of this same tour group, I met a woman, Katherine Vockins who was putting together a Theatre program at Sing Sing… Katherine was recruiting civilians to teach in her new theatre program, Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA). I stepped on board as a directing mentor.

Levitt directing Maximum Will in 2012.

What are some of the differences and similarities between teaching college students and teaching incarcerated folks?

Levitt: Both groups are inquisitive but the energy is different. PPTG is relatively small and tight-knit and meets for two hours each Friday evening in the schoolhouse at Auburn Correctional facility. PPTG had developed its own theatre-training process with exercises in developing writing and performance that serve as catalysts to transformation within the prison setting. This process is pedagogical in that it creates a self-sustaining occasion for collaboration, discovery, growth, and knowledge. The final steps in the process begin as members of the group devise theatre pieces, rehearse scenes and monologues, discuss current events, and share personal stories. Ultimately, at the end of each cycle of training, the incarcerated men devise a 90-minute performance, mostly composed of solo pieces sutured together into a kind of theatrical collage. These are typically presented every 18 months to 2 years.

Cornell students take their ability to go to college for granted and going to classes isn’t particularly “special or extraordinary” for them. Nor do Cornell students tend to focus on their “transformation” or many intimate collaborations. The men in PPTG often talk about how our weekly meetings are like the best “visits” they have. The space is where they can experience a good measure of freedom within a very controlled environment. They often talk about the group as “family.” And the men bring a hunger, energy, and commitment in engaging with the work that surpasses that brought by Cornell students. PPTG members bring a depth of maturity and diversity of experiences to draw upon in their work that far exceeds the reservoir of emotional, psychological, and experiential breadth of the students.

One thing that is unique about PPTG is that we involve students in two ways: I teach a course on Prison Theatre, and those students travel with us to Auburn every Friday evening–our regular workshop night– for one semester and participate in the work with the men. There are six short three-minute videos on the PPTG website where the student discuss their experiences of working with the group… Other students [also] collaborate with the men in writing the scripts and performing alongside the men in the final presentations.

Moller: Some incarcerated persons are hungry for learning. When the Pell grants were withdrawn… many of the men who were intellectually driven were at a loss. Many were smart, resourceful, and ambitious enough to live middle-class lives by selling drugs due to the lack of better resources in their community. Higher education was an anomaly for men of color from the five culturally disadvantaged districts in New York City from which most of these men had come. Furthermore, many had served over ten years, were mature men and ready for something constructive. Theatre wasn’t college, but it offered something unique… Theatre was a magnet that attracted the brightest and in some cases, the toughest men. Plus, there were a few women in the RTA program and although rules are very strict, some men found the opportunity to interact with women satisfying.

Traditional college students often lack maturity as well as focus. First generation parents push their children to take advantage of college as a launching pad to a successful career they could only dream of, but the students themselves sometimes lack readiness. CUNY students are often saddled with part or full-time jobs and family responsibilities. There is a good deal of drama in their lives, creating conflict between financial priorities and family needs.

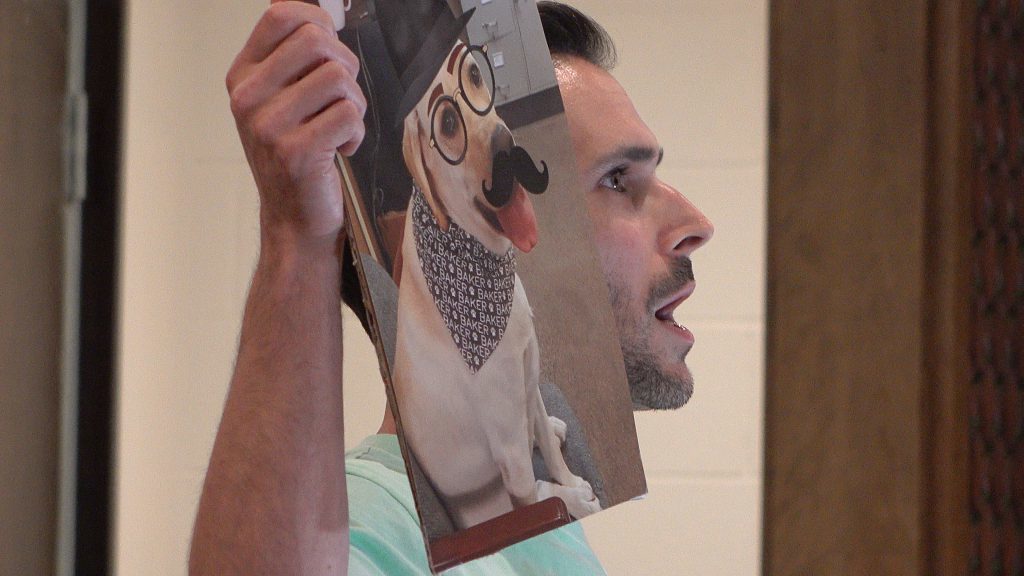

RTA’s Of Mice And Men (2018).

How do you approach an established work vs. a devised pieces as a facilitator?

Levitt: We create mostly devised work. Our two-year cycle includes inviting new members to join. After many discussions among the current members, men are nominated for the group and given a seven-page essay a question application to fill out. That application, when completed, is presented to the entire group and after that review, men are invited to join the group. There is a six-week workshop that uses a series of exercises and improvs, chosen and led by the continuing members. At the end of the six weeks, there is a conversation between the continuing members and the new invitees. The continuing members decide if they want all the invitees to stay and move forward, and the invitees decide if they want to stay. Each new group of members is referred to as a “generation.” …After the six week workshop, the core of the work begins with Characterology, drawn from bioenergetics, and Rasa Boxes. Then other text work and improves begin. After about 12 to 14 months, the group begins to create pieces for the next presentation.

We use texts as exercises to work on speech and diction as well as applying the earlier work in the process to characterization. Too established texts give the men insight into writing, character construction, and the use of language for the stage.

We’ve done one piece, Maximum Will, which used material from Shakespeare interwoven with original material created by the group members.

Moller: The RTA program is quite established now after 20 plus years. There is a steering committee that selects the play from four or five options. The choice is approved by the administration and we hold auditions that are restricted to the men or women in the program. Beginners generally do not get a crack at the main roles but first must put in their time backstage to learn the ropes. Roles are cast and then we proceed like any other production with table readings (student desks in a circle) and then blocking, etc. We have production meetings, rehearse in the schoolhouse and then move to the performance space for tech and costumes. Costumes come into the facility in a highly organized manner. Each character has a bag with all costume pieces indicated on the outside of the bag. Every item in each bag is itemized on a gate clearance list. This is, of course, a big deal for security since all items are considered contraband. The set is constructed by the men in Vocational Department then moved to the performance space. Generally, rehearsals occur twice/week and as the opening gets closer, several afternoons, as well.

RTA’s Twelfth Night.

What is the purpose of using these two different methods of theatre-making?

Levitt: We don’t stage established texts but have drawn upon Shakespeare once as a springboard for the men’s own work, it was at Michael’s insistence that we tackle Shakespeare. If we use previously written texts in performance, it is for the purpose of framing the work that preceded or follows it.

Moller: Since my work has either been in Applied Theatre where participants are both actor and audience (a classroom experience) or established theatre that culminates in a performance for an outside audience, the performance component is the distinguishing factor. In my experience, when there is a final presentation to the public, the cast and crew develop a sense of mutual responsibility which results from working intensely with one another. Given differences in sexual orientation, culture, and race, the participants learn to prioritize the project over their differences and individual needs. For the betterment of the whole, they resolve conflicts, reinforce solidarity, and establish community.

Performance is a positive experience for both actor and audience; applause reinforcing that the program participants are more than their crimes. As [an] audience, the population sees the actors as surrogates and everyone is raised up by their success in the production. The actors often achieve celebrity status as their success is echoed by both inmates and staff alike, enhancing self-esteem. The civilian audience takes with them a new understanding of the humanity behind the walls.

Photo from the PPTG’s, The Strength Of Our Convictions: The Auburn Redemption. (2018) Photo: Peter Carroll.

Would other types of art be as effective in achieving the goals of your programs?

Levitt: I think the key to any type of art in prison being effective is sustainability. The program needs to be permanent and ongoing, with the incarcerated having a key role in how the program chooses content and evolves over the years. Group members need agency over the ”subjects” and content of the workshops. And while they may begin by imitating or copying “masterworks” in order to emphasize the importance of fundamentals in the form–of craft as well–whether the discipline is art, music, dance, creative writing, etc–the incarcerated should be given a chance to create their own work and devise their own forms of expression within the discipline. And group members should be able to participate for as long as they desire or remain at the institution. And it’s extremely productive if the older members can mentor the incoming new members of the group.

A sustained program, such as PPTG contributes to members’ ability to manage their everyday life in prison. They learn how emotions manifest themselves in others, as well as themselves, they become aware of not only how to manage their emotional life but also how to avoid situations that might be detrimental. As facilitators, we gain as much or more personally and professionally from the sustained, year-round, weekly contact with the group. And we gain perspective on what it means to be human in a larger scale. Or, as one member of PPTG describes the benefits of the group for himself, what it means to be “human again”–how on can reclaim one’s agency and power as a whole person.

The men of PPTG are not only collaborators–with each other and with the facilitators–but are the real researchers, digging into their own lives, excavating memories, assessing their traumas, and coming to “own” the reasons for their incarceration. And finally, the men also uncover and assert the notion that they are more than their crime, that they are family men: fathers, husbands, sons, brothers and so on.

Moller: I don’t believe so. Theatre is the most representative of the arts. The ability to walk in another person’s shoes is unique to theatre. There is no art form, except perhaps for opera, that fully represents the expressions of the human form and use of language to a live audience. Albert Bandura, a social scientist, believes that we learn not only from direct experience but from watching those around us, whether in life or in electronic form. Social learning theory helps to explain how experiential learning helps to imprint behavior on us. Additionally, theatre combines literacy with the learning of empathy, one of the most important benefits of theatre. To portray a character other than oneself is to see from another perspective. If one can see from another perspective, empathy is possible, even behavioral change.

The audience awaits PPTG’s show, Maximum Will (2012).

Since you’re well established in the prisons you work in, does it seem like the administration is on board or do you find yourself running up against administrative obstacles?

Levitt: The entire Executive Team at Auburn changed over during the process of creating the last performance this past May. We–meaning the facilitators and the men of PPTG–strive to keep excellent relations with the administration and to be clear about our goals and purposes. Security is paramount in Maximum Security facilities and one needs to recognize that reality. We’ve had terrific cooperation from administrations both in the past and currently.

Moller: Several of the facilities regard the program with well-earned respect, such as Sing Sing and Bedford Correctional. Others, less progressive, are staffed by individuals who resent the perceived privileges granted to offenders or would prefer their jobs to be easier. I believe that it is difficult to prevent errors. If a practitioner makes a mistake and is caught with a note from a prisoner, if a prisoner makes a mistake and a costume is missing after a production, if a videotape of a production gets into the wrong hands, the program in that prison is shut down. All the above has happened, even with the best of intentions on the part of all. Each production is a small miracle and the members of the program do their best to protect it.

Your programs seem to be about both theatre education and theatre therapy. I’m wondering how you would define each of these terms in the context of your program and talk about where there is overlap and where there isn’t.

Levitt: This is a complex question. I would point readers to an article, co-authored with my colleague and co-facilitator, Nick Fesette–published in Teaching Artist Journal: Pedagogies Of Self-Humanization: Collaborating To Engage Trauma In The Phoenix Players Theatre Group.

Moller: Theatre has social and educational benefits, such as emotional literacy, learning empathy, practicing discipline and building community. It is also an excellent vehicle for anger management. People who are incarcerated do not have the luxury of blowing off steam without being ticketed or receiving a violation. Theatre is a wonderful release for emotions which can be channeled into an art form. Emotional management is extremely important as is self -presentation. These are interpersonal and social skills that appear to be enhanced through theatre.

I have also found institutional benefits from our studies. In one study with a matched control group, members of RTA had fewer and less severe infractions than non-RTA members. They also had more positive outcomes than the controls, such as moving up from a maximum facility to a medium facility. Another study on the RTA program suggests that more RTA members with GEDs move on to higher education at a higher rate than non-members.

There are also therapeutic benefits to theatre such as the building of self-esteem and often, there is some healing which occurs that is transformative. However, this is a welcomed byproduct of the process and not the purpose of theatre education.

There is, of course, a therapeutic form of theatre: psychodrama. The purpose is explicit: healing. In psychodrama, patients act out a personal unanswered need while supported by others. Sociodrama, created by the same man, Jacob Moreno, is a form that I often use. However, sociodrama is focused on collective (group) issues, unlike psychodrama which is based on personal ones.

RTA’s Macbeth.

Both of your programs talk about the positive outcomes inmates experience as a result of this work. Are either of you trying to make these programs standard offerings in maximum security prisons?

Levitt: Because PPTG was founded by incarcerated people as a grassroots program, it wouldn’t work for “civilians” to introduce the program into other facilities. Michael was transferred to Attica a few years ago and has begun a theatre group there. Other members of PPTG have been moved to other facilities and could, if they desired to, propose similar programs at their facilities. It’s one of the limitations of PPTG’s spreading to other institutions that it remains–to cite one of the founding documents– “by and for incarcerated persons and communities.”

Moller: I have worked as a director, directing mentor, artistic director and board member of RTA. Currently, the program is in five facilities. With rare exception, the practitioners do not get paid. This year, for the first time, a grant will allow the organization to pay their volunteers a small stipend. As I mentioned, before the issue of reentry became visible in the media, there was almost no money for programs.

Katherine Vockins is extraordinary in her leadership of RTA, however, the challenges to keep programs running in 5 state prisons is daunting. Maintaining open communication is challenging, given that prisons with limited staffing see their main function is security. The paperwork for programs requires an experienced, diplomatic RTA staff to keep things moving.

Given the positive outcomes of the studies conducted on RTA, the incredible press coverage and the accolades of the civilians that attend the performance,–and most importantly, the progress of the members,–perhaps there is hope in the future for a continuous cycle of grants that will allow the organization further growth. Who knows what the future will bring?

PPTG’s An Indeterminate Life (2014).

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Taylor L. Ciambra.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.