As an art form routinely accused of contemporary irrelevancy, opera rarely makes headline news. But a new staging in London of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell (1829), a work perhaps best known today for bequeathing the world the theme music of the TV series The Lone Ranger, has garnered international media attention for including a scene of gang-rape and full-frontal nudity.

The scene was apparently greeted with sustained booing from the audience at both the dress rehearsal and opening night last week. Catherine Rogers, an opera singer who was in the audience, concluded in a blog post that the scene in question was meant to shock, to be sure, but did so cheaply, “without protecting the very people who’s plight it is designed to highlight”; that is, it was done without any warning.

It would be inappropriate to comment on the finer details, of course, without having seen the production firsthand. But the controversy raises a number of issues with wider ramifications.

To begin with, it points to one of the underlying reasons why opera is prone to accusations of irrelevancy. To put it bluntly, we don’t like to think of opera as realist drama. Its theatrical conventions and clichés tend instead to evoke a kind of mythic realm where humans act, or – should we say – sing, above or outside broader history.

When opera is unmistakably set in a particular time and place, say the Paris of Puccini’s La Bohème (1896) or the Seville of Bizet’s Carmen (1875), such settings provide colorful backdrops. We are not really being asked to consider the desperate plight, say, of the Parisian or Spanish female working poor.

This is why the kind of controversy that has erupted in London is so peculiar to opera. By comparison, when similarly distressing scenes occurs in a film or theatre they generally raise much less critical attention, let alone backlash – although Game of Thrones has been on the receiving end of much criticism for its portrayal of rape, in the show’s most recent season, and in others.

The author of that phenomenally successful fantasy-book-turned-TV-show, George RR Martin, has justified the inclusion of so many such scenes of violence against women in his plots by arguing they reflect the sad reality of war in our own cultures. This is a valid point – but only if the context in which they are placed does not make such scenes seem more gratuitous or pornographic than historically informative. (As far as the TV series is concerned, at least, this is a moot point).

The desire to make operatic plots similarly raise our political and moral conscience is perhaps the chief justification for so-called Regietheater, a theatrical conceit that licenses an opera director to transform, or simply ignore, the original settings and conventions of an historic operatic work.

The depiction of women in opera presents a particular challenge. In a now-famous study entitled Opera; or The Undoing of Women (1979), the philosopher Catherine Clément examined the way in which traditional operatic plots have more often than not centered around the physical or psychological destruction of a female character. Thus, she argues, opera:

Is no different from the other artistic products of our culture; it records a tale of male domination and female oppression. Only it does so more blatantly and, alas, more seductively than any other art form.

In opera, Clément says we watch “women die – without anyone thinking, as long as the marvelous voice is singing, to wonder why”.

Guillaume Tell, however, is not Carmen, or La Boheme, or indeed Tosca, or Madame Butterfly. Based on Friedrich Schiller’s play of the same name, it centers on the eponymous legendary Swiss revolutionary hero and his quest for both love and liberty. Sure, violence is in the plot but was it justified to present it in such a graphic, and gendered, form?

Kaspar Holten, the Artistic Director of the Royal Opera House, concluded that it was, writing last week:

Let me assure you that we wanted to put the spotlight on rape as a horrible and terrifying crime and that our intention in doing this was to remind us all how this weapon is being used in warfare around the world. Whether this is the right way to do it, is a relevant and important discussion, but I want to make sure the intention is understood correctly.

But, as the UK critic Hugo Shirely mused in 2014, grand operas such as William Tell were first and foremost “written to exploit and reflect the power, resources and tastes of mid-19th-century Paris”, and “tended to favour history and its battles for the scenic opportunities they afforded rather than for the lessons they taught.”

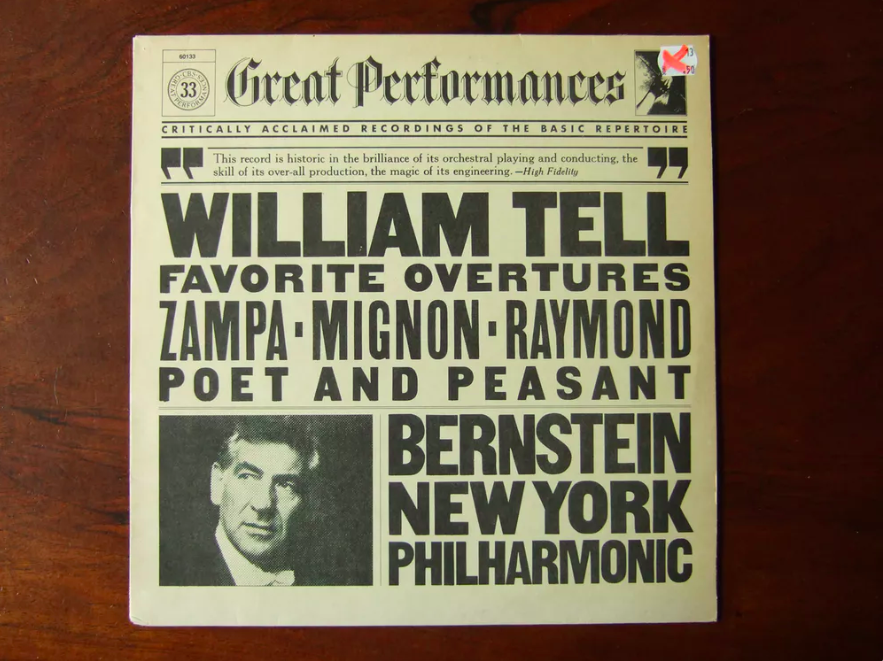

Rossini’s William Tell is a widely performed and recorded opera. Piano, Piano!/Flickr

Of course, all such historical stories inevitably unfold, as the German philosopher Walter Benjamin famously noted, against a backdrop of both civilization and barbarism. But romantic and political heroism is the dramatic focus of Guillaume Tell, not the horrors of war per se.

And lest we think that this was because the original Parisian audience simply wanted to avoid these less comfortable truths, we need only to recall what the lived experience for many of them must have been. The Second White Terror, after all, had occurred only 15 years earlier, and another French revolution was less than a year away.

Political violence was perhaps as stark and as distressingly accessible to that audience as it is today for us in the era of ISIS uploads to YouTube. Maybe it was more pressing, instead, for that audience to remind itself that qualities such as individual heroism, love, nobility of spirit, stoicism, and emotional sincerity, nevertheless still matter in troubled times.

These are, furthermore, qualities that the musical character of 19th-century opera (all too often overlooked in these debates) is especially well suited to convey.

At its best, opera can, indeed, be a powerful form of allegorical theatre. Precisely its unrealistic, “fantastic” character can reveal to us a great deal about ourselves and very contemporary concerns, just as Luke Buckmaster has argued is the case for Game of Thrones.

I wonder then whether, in the rush to present a more overt message, opera directors risk simply miscomprehending the medium?

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on July 5, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Peter Tregear.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.