It’s characteristic of the Shaw Festival’s new artistic regime that this summer’s lunchtime theatre offering begins with cast members being themselves—by treating the audience to a mini-concert of Irish balladry. One of them strums a guitar, another presides at the piano, and nationalistic numbers like Foggy Dew are sung with appropriate fervor.

There’s also a bit of conversational back and forth with the audience, in deference to current artistic director Tim Carroll’s love for what he calls “two-way theatre.” But eventually, the Canadian accents are dropped and the four performers submerge themselves in matters Irish as viewed through the sardonic prism of George Bernard Shaw more than a century ago.

O’Flaherty V.C. is Shaw’s playful playlet about the hypocrisy of war and the bogus mythology of heroism. There are those who see it as a major contribution to the Shavian canon—but there’s little evidence of that in the production that unravels before our eyes at the Royal George Theatre.

Shaw’s thoughts on war surface repeatedly throughout his canon—in plays like Arms And The Man, The Devil’s Disciple, and Man Of Destiny (another play available at the festival this season) and most magisterially in Heartbreak House, an allegorical masterpiece arising out of the carnage of the First World War.

O’Flaherty V.C. is a far slighter work, a sort of flippant garnish to his inflammatory essay, Common Sense About The War, but still politically provocative, given that it has the audacity to focus satirically on the contribution of anti-colonialist Ireland to the war effort.

GBS’s inspiration was apparently the real-life example of Irishman Michael John O’Leary who was awarded the Victoria Cross in 1915 for “conspicuous bravery” in killing eight Germans and capturing two others. We’re told in a lively program note by Shaw historian Leonard Conolly that O’Leary became a poster boy in the drive to recruit other young Irishman to join up and “emulate the splendid bravery of your fellow countrymen.”

But Shaw’s little play turns our hallowed notions about heroism on their ear by giving us a young V.C. recipient—Dennis O’Flaherty by name—who has the effrontery to admit that heroism had nothing to do with it: the reason he killed all these Germans—“God knows how many…” was because he had to do so before they killed him. As for “patriotism”—well, he’s similarly forthright in declaring that the best route to a peaceful world is to “knock patriotism out of the human race.”

There’s an undeniable irony in the spectacle of this young plain-spoken soldier being sent home from the front to recruit more young Irishman for the trenches—especially when he’s honest enough to declare that appealing to their patriotism is a less effective device than simply telling them that signing up is a good way of “getting out of Ireland.”

Shaw’s readiness to use a young Irish private as the mouthpiece for such sentiments explains why Dublin’s famed Abbey Theatre changed its mind about premiering the play for fear of rioting in the street. Instead, its first performance was an amateur one, on the Western Front in 1917 and featuring members of the Royal Flying Corps.

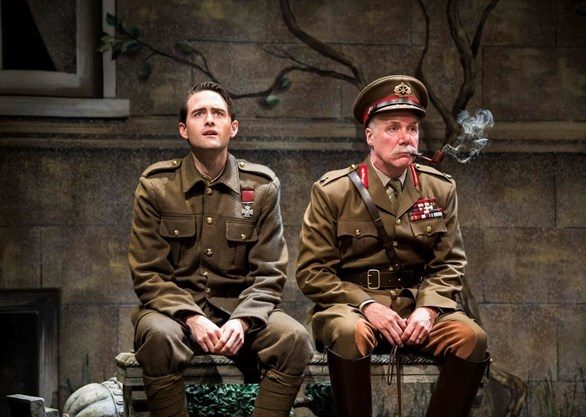

There’s enough in Shaw’s text to promise an engaging and often biting 40 minutes of theatre. And although, as always, the play serves Bernard Shaw’s purpose as a peg on which to hang his ideas, there are also a couple of springboards with the potential for enjoyable dramatic conflict. The first has to do with Dennis’s encounters with an Irish Colonel Blimp in the mustachioed person of General Sir Pearce Madigan, an aging recruiting officer increasingly unsettled by his young charge’s penchant for uttering the wrong sentiments on behalf of the war effort. The second conflict has to do with the reaction of young Dennis’s fiery nationalist mother when she realizes that he won his glory fighting for the hated English.

There are ingredients here for a provocative Irish broth of a comedy. So what’s gone wrong in this latest Shaw revival?

There’s an element of the not-quite-believable in Sue LePage’s set design—appropriate, perhaps, for a comic fable, but not a venue in which this production can rest comfortably. There’s an element of uncertainty in Kimberley Ramparsad’s direction—a trouble with tone. How acutely should we be feeling Dennis O’Flaherty’s pain and distress over what he endured? Or are we ultimately to opt for the knockabout farce of the final moments and the comic irony inherent in Dennis’s conclusion that he’d rather return to the carnage of the battlefields than continue enduring the emotional mayhem he suffers on the home front?

The performances, with one exception, seem oddly tentative. As O’Flaherty, Ben Sanders reveals a pleasing stage presence, and a sharp sense of character, but this is not a subtle piece of writing. Underplaying is not necessarily the right way of dealing with the arguments that Shaw is hammering home. Many years ago, Ian McKellen rightly judged that bravura acting was the safest way of making the part work, and the result was one of his early acting triumphs.

Then there is the surprisingly subdued contribution of Patrick McManus as the general. McManus, an actor with a gift for bringing off outbursts of apoplectic fury when the occasion demands, sadly resists the temptation here—but he does fiddle a lot with his pipe.

Then there is the problem of dealing with a troublesome defect in the text—the fact that in the first half of the play Dennis is literally quaking with fear over an approaching encounter with his firebrand of a mother. So there’s a delicious build-up, which can leave an audience quivering with delightful expectation over what will happen during the inevitable confrontation—but then the text undermines everything by providing no satisfactory pay-off. Shaw then lets us down, unveiling a Mrs. Flaherty who is nothing more than a conventional caterwauling Irish stage mother. In this role, Tara Rosling can’t find a way of getting beyond stomping about ferociously and delivering a sharp-tongued harangue that invokes caricature and little more

What we seem to be getting in these performances (on occasion incomprehensible because of the accents) is a series of individual acting turns, variable in their effectiveness, and failing to mesh in a satisfactory whole. Still, Gabriella Sundar-Singh does merit a star for bringing amusing credibility to the role of Dennis’s cheeky sweetheart.

(O’Flaherty V.C. continues at the Shaw Festival until October 6. Further information at shawfest.com or 1-800-511-7429)

This article originally appeared in Capital Critics’ Circle on June 22, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jamie Portman.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.