Due to the current financial crisis in the tertiary education sector in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the university where I teach Theatre is proposing to cut 230 jobs.

The cuts are far-reaching and affect languages, music, secondary teaching, geophysics and many other subjects. The proposal includes cutting more than half of the theatre academic staff and one technician. This would make it impossible to deliver the programme as it currently stands and undo over 50 years of hard work building a full theatre programme. It is also proposed that theatre will no longer be a stand-alone programme and will be merged with English Literature. My colleague James Wenley has written an article putting the cuts at our university in the context of wider challenges affecting performing arts education in Aotearoa.

Thinking about what would be lost if these cuts proceed has led me to attempt a brief history of our Theatre Programme. As a graduate and a staff member here for nearly 25 years, I’ve witnessed first-hand the massive contribution this programme has made to the arts in Wellington, in Aotearoa and beyond.

The programme was established in 1970 as Drama Studies. It was the brainchild of an English Professor, Don McKenzie, who had a passionate commitment to creative arts and created a lectureship in drama with a commitment to teach drama not as literature but as a dynamic live artform through a combination of theory and practice. That commitment to integrating practical creative work with academic study has never wavered and remains as strong today as it was 53 years ago.[1]

The Drama Studies programme was launched by an energetic theatre director and scholar Phil Mann, who had come from the U.K. via California. Phil provided the model for many scholar-practitioners who would follow him in later years, regularly directing professional theatre productions in the city alongside his teaching role. His many acclaimed productions included the now-classic world war two drama Shuriken (1983) written by his close colleague in the English Department Vincent O’Sullivan.

The original course was called Drama 2: Introduction to Drama, and was restricted to 30 students. Among the students in the first class was Robert Lord, a playwright who in 1973 would become one of the founders of Playmarket, the national scriptwriters agency and script development orgnaisation. Drama 2 was based in a run-down house in Kelburn Parade until a small studio theatre was created in the house next door at 93 Kelburn Parade. This was known as Drama House and was licensed for an audience of about 40. Despite its small size, Drama House proved remarkably flexible and was the site of many memorable productions, and continues to be used as a performance and workshop space today.

After a couple of short-lived appointments, in 1978 Phil was joined by David Carnegie, a Canadian theatre scholar who had previously run Otago University’s drama programme and was one of the founders of the Fortune Theatre in Dunedin. With David’s expertise in dramaturgy and theatre history, he and Phil were a formidable team. Recognizing the close links between the professional theatre and the emerging New Zealand film industry, they introduced courses in film production, history and criticism. From 1979 these were taught by Russell Campbell, who, like Phil, balanced his teaching with creative work in the film industry. The close link between the study of film and theatre was unique to Victoria, and a strong attraction for students aiming for careers in film, television and performing arts. In 1986 Vic students created the scholarly magazine Illusions, which covered New Zealand theatre and screen, and was initially edited by Russell Campbell and based in the theatre and film precinct in Fairlie Terrace, which also housed the Playmarket office for some years. So Drama Studies had become a catalyst for building networks in theatre and film in Wellington and beyond.

In 1983 drama students and academic Adrian Kiernander created the Wellington Summer Shakespeare, which continued as a summer tradition for the next 40 years. Some of the first productions were led by some of New Zealand’s leading theatre directors – for example Colin McColl, future director of Downstage and the Auckland Theatre Company, Simon Bennett, co-founder of BATS Theatre and a prolific television producer and Dame Miranda Harcourt, internationally renowned screen acting coach.

In the 1980s Phil and David were joined by John Downie, an English playwright and director who was recruited to teach both theatre and film. John introduced courses in scriptwriting, and together with Phil encouraged the growth of group-devised theatre, which in turn led to a tradition of students forming their own theatre companies to create original work. In the ‘90s some of these companies – such as Trouble and Jealous – created award-winning productions.

In 1990 Theatre became a majoring subject in the BA, although there were still only courses at second and third year levels. In the early 90s it became the Department of Theatre and Film and another milestone occurred in 1994 when the department moved into much larger premises in the former Architecture School at 77 Fairlie Terrace. The theatre was named Studio 77, a vast improvement on the rudimentary Drama House around the corner, with the luxury of a solid, well-designed lighting grid, flexible seating blocks, walkways running around the upper level of the theatre and an audience capacity of up to 100 people.

In the late 1990s, the university re-structured departments into schools, and theatre and film became programmes in the School of English, Film and Theatre (soon to be joined by Media Studies). I joined the programme in 1999, following Phil Mann’s retirement, to find it was on the cusp of a major expansion of staff and programmes.

In 2001, after some years of planning, the Theatre Programme joined forces with Toi Whakaari: NZ Drama School to introduce the Master of Theatre Arts in Directing (MTA), which was taught for the next 15 years. This was a rigorous two-year course in director training, with the first year mostly based at the university, mixing theory and practical work. The second year was primarily creative work, directing a variety of productions, based at Toi Whakaari. Today, many MTA graduates are leaders across creative industries in New Zealand and overseas.

Also in 2001, the programme introduced an honors degree which meant for the first time theatre students had a pathway to studying for an MA or PhD. This led to an exponential increase in postgraduate students. In 2005 Theatre introduced its first stand-alone 100 level course THEA 101. For the first time Theatre had a full academic programme from 100 to 400 level and a growing number of postgraduate students.

The rapid expansion of the programme required an increase in academic and technical staff. Theatre got its own technician, Anneliese Mudge, after some years of sharing a technician with the Film Programme. As students increased so did the academic staff numbers, from 3 to 6 over the years 2001-5. Bronwyn Tweddle brought expertise in German and physical theatre, Matt Wagner in Shakespeare and dramaturgy, and Megan Evans in Asian and Intercultural theatre, building on the work Phil Mann had done in introducing Non-Western theatre into the programme. Courses in scenography were introduced, encouraging many students into careers as designers and technicians for theatre and screen industries.

In 2016 a review found that the MTA had become financially unsustainable, so it was discontinued, ending the formal partnership with Toi Whakaari. However new partnerships emerged with other university programmes, and a one-year MFA (Creative Practice) was introduced in 2018, with streams in Design, Film, Music and Theatre. From the beginning, this more flexible qualification has been popular with recent graduates as well as established practitioners aiming to develop their practice.

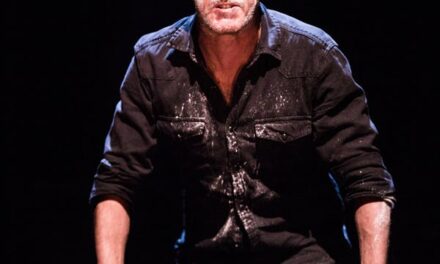

The Cyranoid THEA 301 production 2023 Directed by Nicola Hyland. Photo: Bebby Photography

In the last ten years there has been an influx of new and diverse academic and technical staff into the programme, representing a fresh generation of artist/scholars and introducing new areas of expertise including Māori performance, children and young person’s theatre, improvisation, devised theatre, musical theatre, producing, site-specific theatre, arts marketing, production and stage management. The programme continues to mount full-scale student productions in Studio 77 alongside a range of smaller performances and an annual MFA season at BATS Theatre.

The roll call of graduates from Drama Studies and the Theatre Programme includes many who have gone on to high-profile arts careers. Our graduates form the backbone of the Wellington theatre industry, working in management, technical and creative roles at BATS Theatre, Circa Theatre, Taki Rua Productions, Playmarket, Capital E National Theatre for Children and Creative New Zealand. There are also many more who have used transferable theatre skills such as teamwork, creative leadership, improvisation, marketing and communication to forge careers in a multitude of fields. The tradition of students forming their own theatre companies continues to this day, with strong links to BATS Theatre and the Wellington’s NZ Fringe, both ideal platforms for new generation work. From its earliest days with Phil Mann and David Carnegie, the Theatre Programme at Te Herenga Waka -Victoria University of Wellington has been an integral part of the arts eco-system in Wellington, and is connected to theatre organisations and academic networks throughout Aotearoa and internationally.

As I write, there is hope of a deus ex machina – a last minute reprieve although a government funding boost for universities. Whether or not this occurs, the proposal to significantly reduce New Zealand’s oldest and largest university Theatre programme must be a reminder of the need to work tirelessly to ensure that the value of performing arts education is recognized by those in power.

[1] For more detail on the founding of Drama Studies, see Rachel Barrowman, Creative Victoria. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2018, 46-58.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David O'Donnell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.