Natalya Vorozhbit is Ukraine’s leading playwright and co-author of Maidan: Voices from the Uprising, a verbatim play about the recent political protests in Ukraine. The play premieres in an English translation by Sasha Dugdale at the Royal Court this month. Verbatim is a documentary playwriting technique that theatre artists across the globe use as a way of responding to current events and giving voice to otherwise marginalized members of their societies. It involves conducting interviews with those connected to the events under discussion, which are then transcribed, edited and composed into a play text. Vorozhbit discusses how the play came to be, her own experiences at the Maidan protests, and her work as a playwright both in Ukraine and abroad.

Molly Flynn: How did you decide to write a play about the people of Maidan?

Natalya Vorozhbit: In December, when the protests first began, I started meeting a few times a week with the director Andre Mai and our Ukrainian New Drama colleagues. At these meetings, we exchanged our impressions of what was happening. We felt strongly about the fact that we needed to react not only as citizens, but also as professionals. It was clear even then, that what we were experiencing was something definitive, something historic, and that we were living through a time of change. We thought of using a diary format in our very first meeting. So, we went to Maidan, where the protesters were camping out and we asked them to tell us about their experiences of the day-to-day and about key events that had taken place. We recorded all of the interviews on video or on Dictaphones. Then, in March, we started compiling the interviews. We transcribed and edited them to compose a script for the play. The basic idea was to try to capture the event, to capture the emotions. It can be easy to forget things at times of such intensity. A month after some kind of event, a person recounts it completely differently than the way they’d describe it while it’s actually happening. People reflect on how it all came to be, they interpret the event and justify what happened. What we collected were fresh and unaltered reactions.

The play is composed of interviews with people from different social demographics; students, doctors, Cossacks. How did their opinions about the protests differ from one another?

The Cossacks simply said – we don’t like the old regime, we want to live in a normal country, and we will be here until the end. The students understood very clearly that they wanted to get rid of the old regime – they wanted freedom: freedom of choice, free elections, freedom of movement. They were shocked when the violence started. How could it be that in the twenty-first century they were beaten for attending a political protest?! It just didn’t make sense to them. What kind of Soviet mentality was this?! These were free people with a modern mindset. The doctors, in their interviews, almost never expressed their opinions about what was going on. They simply told us what they’d observed. That’s probably a result of their profession. Almost nobody used their interviews to describe why they came to Maidan. That was obvious to everyone.

Were there any interviews that were especially surprising to you?

With over 30 hours of interviews, it is, of course, difficult to choose just a few. One surprise was that I found my aunt at Maidan who I hadn’t seen in 20 years. She experienced it all and we included her interview in the play. There was another incredible interview with a teacher from the University. He had been to see a neurologist because every time he heard the Ukrainian national anthem at Maidan, he started to cry. He told us how she cured him. The interviews with students were really remarkable – they were so surprised about what was going on. Maidan itself was an astounding. The people, the spirit, the past, the mysticism, the cosmos – It was as though some kind of portal just opened up in the centre of Kiev and out came the heroes of the past, long-forgotten values and folkloric melodies from the middle ages. The voices of our ancestors crept in and the live voice of Shevchenko resounded. I felt it so strongly. The Cossacks were real and the anthem they sang was the real one. They sang the way our ancestors must have sang around the fire asking the gods to send them rain and food in exchange for their bodies and souls. The spirits heard our call. They claimed their sacrifices, and they continue to do so. We are waiting for freedom. In those days, the Gods were also not so quick to give away the rain.

You were involved in the protests from the very beginning, right?

Yes, I was there from the first day protesting against Yanukovych’s decision to join Russia’s customs union. Until that time the country had been working towards greater integration with the EU. In my circles, everybody took an active part in the protests. We all went to Maidan to help however we could, physical presence, food, medicine, friendship, building barricades…

Was there a particular moment when you understood how significant these protests, and the tenacity of the protesters who stayed out in the square in sub-zero temperatures, could be for Ukraine?

The first time I felt fear. It was the night of the 10th and 11th of December when the police and Berkut started storming the protesters. It was freezing out and about 500 hundred people were still there when we left at midnight. The assault started at 1 am. This was already after the attack on the students and we understood that history could repeat itself. A thousand soldiers descended on Maidan. The bells of Mikhailovsky church began to ring calling to the people of Kiev for help. And people came from all over the city to defend Maidan. They arrived by car and on foot (the metro had already closed at that point). They came straight to the center of Maidan knowing full well that it could be dangerous and, on the way, they looked into the faces of the soldiers surrounding the protesters. I stood there with a friend, right by the stage, until 7 am the next morning. The square was absolutely full of people, and that is when I realized that this was all real. There was so much pride for our people, for how they stood up to the attack. 500 hundred people are one thing, but 10,000 is something completely different.

In other interviews, you’ve said that you don’t like using the verbatim playwriting technique. Why is that? And why did you decide to use verbatim for this play?

I don’t like verbatim because it involves so much technical work (collecting interviews, transcribing, editing). I’m lazy and I don’t like taking interviews. The genre leaves very little room for the author’s voice. There’s really no possibility to talk about yourself. But this was the only way to talk about Maidan. When you write a play or create any kind of artistic work, you need distance. You have to let time pass. We haven’t lived through this yet so we can’t reflect upon what has happened, and we won’t be able to anytime soon. That’s why verbatim was the most honest and appropriate method for us to use to embody these events. Any other way would be dishonest. An attempt to make a feature film about Maidan right now would be an absolute failure. A documentary is the only way.

You grew up in Kiev and moved to Moscow to study playwriting. In Moscow, you became a leader of New Russian Drama and one of the founders of Teatr.doc – Moscow’s first documentary theatre venue. What was it like when you moved back to Kiev in 2004?

Yes, that’s right. I lived in Moscow for 10 years and returned to Kiev in 2004 in the wake of the Orange Revolution. I felt very strongly about those protests as well and was an active participant. It felt natural to return at that time because subconsciously I always wanted to come home. I was never comfortable in Moscow. But soon after I came back I felt like I was in a void. All my friends and colleagues, everyone I was the most interested in remaining in Moscow. I had a nice home here, I felt comfortable, but I didn’t have any like-minded people. There wasn’t any interesting contemporary theatre. But together with a few people I knew, I tried to build a community conducive to the creation of a new kind of theatre. For example, we founded the theatre festival ‘A Week of Relevant Plays’. That’s how we discovered some new names in playwriting and began creating a community for New Ukrainian Drama. Our work is starting to become recognized and some state theatres have begun staging works by contemporary authors. Life here has definitely become more interesting, but we are still at the beginning of this journey.

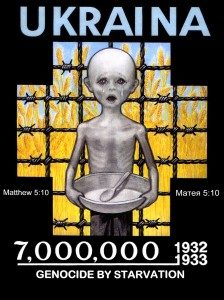

Your play The Grain Store is based on stories your grandmother told you about Holodmor. It was commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company and premiered in Stratford-Upon-Avon in 2009. Is it true that the play has never been staged in Ukraine? And, if so, how could that be?

It is true, the play has never been staged in Ukraine. In 2008 there was a young director who spent the whole year rehearsing it in Kolomyia, in Western Ukraine. That was at the time of the Orange president, Yushenko, but when the regime changed and Yanukovych took office the play was banned a week before its premiere. The topic of Holodmor became immediately irrelevant. Also, The Grain Store is an expensive production, it was written on a grand scale for the Royal Shakespeare Company and our theatre is a poor theatre. And, lastly, our audiences don’t like to suffer. Or, more accurately, our directors believe they don’t like to suffer and therefore choose not to stage plays about the most important topics for Ukraine, such as Holodmor.

Poster by Leonid Denysenko

A lot of the English language media coverage about recent events in Ukraine has focused on how divided the country is – divided by language, by ethnicity, and by national allegiances. Do you think that’s an accurate portrayal of the situation?

As far as the country being divided by language – that’s a myth. There have been no infringements on language since Ukraine gained independence. Nor have there been any on national allegiances. At Maidan, we stood with people of all different nationalities, including many Russians. At the moment, in Slavyansk, Mariupol and in Donetsk no one is under pressure to speak Ukrainian. But there is a war there, and this war is against all of Ukraine. The country is not divided, it should be said loud and clear that our country is, quite the opposite, united by the sanctity of recent events. There are two regions of Ukraine – Donetsk and Lugansk – that do actually want to secede from Ukraine. I would say that this is a division of social mentality. There is also, of course, the influence of Russian propaganda that has been systematically imposed to activate the criminal spheres in these regions. This wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t been for the intensity of that propaganda. It is no secret that these areas have the most criminal activity of any regions in Ukraine. The entire government has been corrupted. To them, a new government and integration with Europe mean that they’ll lose their influence in the East, and that is something they will fight for in any way they can.

How did you explain Maidan to your 5-year-old daughter?

I tried to tell her the truth in words a child can understand. I often took her with me to Maidan. She even spoke onstage at one of the concerts. She saw the tents and the Cossacks. She searched for her imaginary heroes there and it seemed to her fair enough that she might find them at Maidan. To her, it was largely a conflict between the Cossacks and Berkut. She was on the side of the Cossacks of course. On the night when Maidan saw the most violence when hundreds of people were killed, we could hear the shooting and explosions from our house. As she was falling asleep that night she asked me what the noise was, and I told her the truth. I simply told her in a calm voice. She wasn’t afraid, but she won’t forget.

This article was first posted at http://ceel.org.uk Reposted with permission of the author. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Molly Flynn.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.