Construction began on the Gwanghwamun Public Square in 2008 and was completed in July of 2009. The goal was to transform the traffic-heavy Sejongno Street in the heart of Seoul into a space designed for people. The City of Seoul promoted the development project with slogans such as: “A square that restores the history of Gwanghwamun,” “A square that evokes the atmosphere of the historic capital’s administrative center,” “Korea’s prime public space,” and “A center of urban culture and citizen participation.” Yet recently, Gwanghwamun Square has become the diseased and ailing “body” of Korean society.

On most weekdays, city life in the Gwanghwamun district seems dull and unremarkable. But upon crossing a street and entering the square itself, one immediately notices the yellow Sewol Ferry tent and other smaller tents rustling in the cold wind. These tents, pitched by workers and artists, have stood steadfast for over one thousand days, occupied by people who deserve mourning and remembrance, people who had their basic rights taken from them, people whose satirical voices and words of condemnation have been silenced. These protesters cover the body of the public square like painful wounds. Unless these wounds are treated, unless these silenced voices are restored, the square—and Korean society—will continue to suffer. The wounds will fester until society cries out in deeper pain. Perhaps it will even draw its final breath.

A theatre was built in this wounded body of the square. Former President Park Geun-Hye’s regime used a blacklist to manipulate the culture sector and silence the arts. Moving beyond the initial burst of anger and despair, artists have responded by breaking free from disgraced authority and declaring themselves the Other to state power. Moreover, they have pledged in the name of this Other to embrace all who have been oppressed and alienated. Here, I am reminded of Giorgio Agamben’s words. He writes that the excluded and the exiled are not simply pushed outside the law; they have the potential to halt the law and thus regenerate it. That is why I cannot help but be ecstatic for the Black Tent theatre standing in Gwanghwamun Square.

Theatre Announces Itself as Other

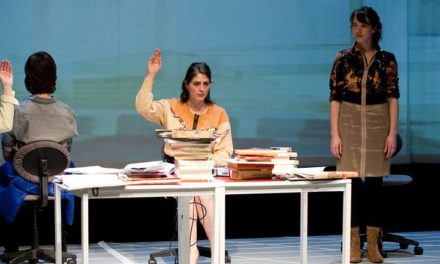

His and Her Closet, 416 Family Theatre Company Yellow Ribbon. Photo: IDSupporters & Black Tent Theatre

The Black Tent theatre has hosted productions such as Red Poem (directed by Lee Hae-Sung, Theatre Company Gorae), His and Her Closet (directed by Kim Tae-Hyun, 416 Family Theatre Company Yellow Ribbon), and Mime (created by Yoo Jin-Kyu and others). Other pieces have patiently awaited their turn onstage, including The Politics of Censorship: Two Citizens (directed by Kim Jae-Yup, Theatre Company DreamPlayThese21) and Ssitkŭm (directed by Lee Yountaek, Yeonhuidan Georipae), even as the President’s impeachment was underway. Taking a closer look, there are several similarities among these productions. They all deal with issues that the current government had not only avoided but did everything in its power to hide and dismiss: the comfort women, the Sewol Ferry disaster, union suppression, irregular labor issues, censorship, and so on. The productions so far had already been presented in existing theatres, although, of course, it is significant for actors and audiences alike that these plays were seen in a public space that harbors the various wounds of Korean society. However, there was one work that stood out among the rest—His and Her Closet by the 416 Family Theatre Company Yellow Ribbon.

His and Her Closet: The Other in the Square

I first saw His and Her Closet, written and directed by Oh Se-Hyuk, at the Guerrilla Theatre in Daehangro in the summer of 2012. The piece dealt with the oppression of workers and irregular labor, but unlike many other plays that explored the same issues, it did not sternly denounce the structural contradictions of neoliberalism. Placing a small wardrobe center stage, it instead relied on playful satire and comedy to focus on the everyday lives of the working class and their strength to endure. This healthy affirmation of life became the heart of the production’s critical power, especially in contrast to the owner characters who use illicit means to lay off factory workers and break up unions. Notably, when His and Her Closet was remounted at the Black Tent theatre, all of the roles—from the apartment complex watchman Honam and his wife Soonshim to their son and the union leader—were performed by mothers who lost their children in the Sewol Ferry disaster instead of the original company members.

Over a thousand days have passed since the tragic incident, but these mothers’ plea for help has still not been answered by the government. So the victims have taken to the streets, the square, and other public spaces in order to be remembered. Meanwhile, the state warns its citizens not to do anything, to stay in place. [Translator’s note: The crew of the Sewol Ferry repeatedly broadcasted the announcement, “Stay in place,” as the ship rapidly sank into the ocean. This was a major factor in the high number of deaths. The phrase is often used critically after the accident, referring to the passive obedience ingrained in Korean society.] Exploiting the public’s reluctance to confront and share the pain, the government coaxed us into forgetting the tragedy. When the government failed to fully silence the victims’ families, it attacked their creditability. It accused them of distorting and exaggerating what happened. The state did everything in its power to absolve itself of liability: from the most blatant denials to the most sophisticated of rationalizations. It tried to render the bereaved invisible. It also insisted that we forget the past and move forward. As the victims’ families were discredited and ignored over and over again, their experiences became something that could no longer be spoken.

His and Her Closet, 416 Family Theatre Company Yellow Ribbon. Photo: IDSupporters & Black Tent Theatre

These mothers stood onstage. Drawing on their memories of standing in the square, camping out, demonstrating, and gathering signatures for petitions, they now stood before a theatrical audience. When the seven performers took on dramatic roles, sometimes with feigned innocence and sometimes with actual awkwardness, the audience saw not only their acting but also the pain and struggle inscribed on their bodies. It became clear that the many plays about the Sewol Ferry over the past two years were all written in an “indirect voice.” This production by the 416 Family Theatre Company, on the other hand, didn’t have to mention the cruise ship by name for these women’s bodies to exceed everything that the Korean theatre had tried to express about the Sewol Ferry disaster.

I imagine it would have been difficult for these traumatized women to open their hearts and connect emotionally with the characters in the play. Setting aside the process of learning how to act in a play, it would have also been difficult to embrace the humor and ironic distance of the characters and the dramatic situations. Psychologists say that the first step towards healing is for others to acknowledge those with trauma as they are, to protect them and build a support structure for them in the community. If that is the case, then the Black Tent theatre allowed these women to resist the state’s illegal and oppressive measures against the Sewol protesters. They could connect energetically with the community without any prejudice or interference. The Black Tent theatre served as a space where they could be free from oppression and rediscover their creative energies. In this theatre built on a public square, at least, audiences no longer saw these women as Other. As we watched them speak and act onstage without inhibition, we realized that we share their situation, oppressed and abused by the state. In the end, it was not by virtue of the play or the actors’ skill that this production was important. Sorry to say to the playwright, it may not even have mattered whether the text was His and Her Closet.

His and Her Closet, 416 Family Theatre Company Yellow Ribbon. Photo: IDSupporters & Black Tent Theatre

The women onstage did not act; they were present. Experts say that the basis of healing is securing a sense of safety and restoring a connection with the community. We must acknowledge these mothers as they are, protect them, and stand with them in solidarity. In that sense, this theatre, this production, and this director all provide promising answers to the question: What should the theatre, as an institution and artistic practice, do? The Black Tent, where things that couldn’t be spoken before are spoken freely and those who couldn’t be seen before are seen clearly, is unmatched as a vital public space where the freedom that we have lost in our everyday lives can be restored. This theatre is not a place for trivial feelings or fantastic dreams. It is the only public theatre that we currently have where we can engage and interact with the Others of our time.

Lee Kyung-Mi is a theatre critic and adjunct professor at the Korea National University of Arts.

Translated by Kee-Yoon Nahm

This article was originally published in Korean Theatre Journal, the official journal of the International Association of Theatre Critics – Korea. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lee Kyung-Mi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.