Every time I go back home, Athens-Greece that is, I make sure to attend theatrical performances. Greece has a long history in theater, deriving from ancient times, and contemporary Athens has become a boiling cultural pot. The years of financial crisis have been devastating to the people, but for Greeks, the sense of community and expression through art have always been the answer to difficulties. There are numerous groups and scenes around the city, and the level of performances is high even though the means are very limited. For that very reason, many monologues are chosen to be presented.

A monologue is what a solo recital is for a musician, an incredibly demanding task that calls for masterful craftsmanship. The performer’s palette of tools – diction, rhythm, nuance, phrasing, stamina, command of all facial and body muscles – needs to be in a state of readiness. At the same time, the creation of a monologue, dramaturgically, calls for a playwright who is also in command of his tools and all theatrical devices and is able to sustain the audience’s interest for a whole evening through the mouth of a single performer.

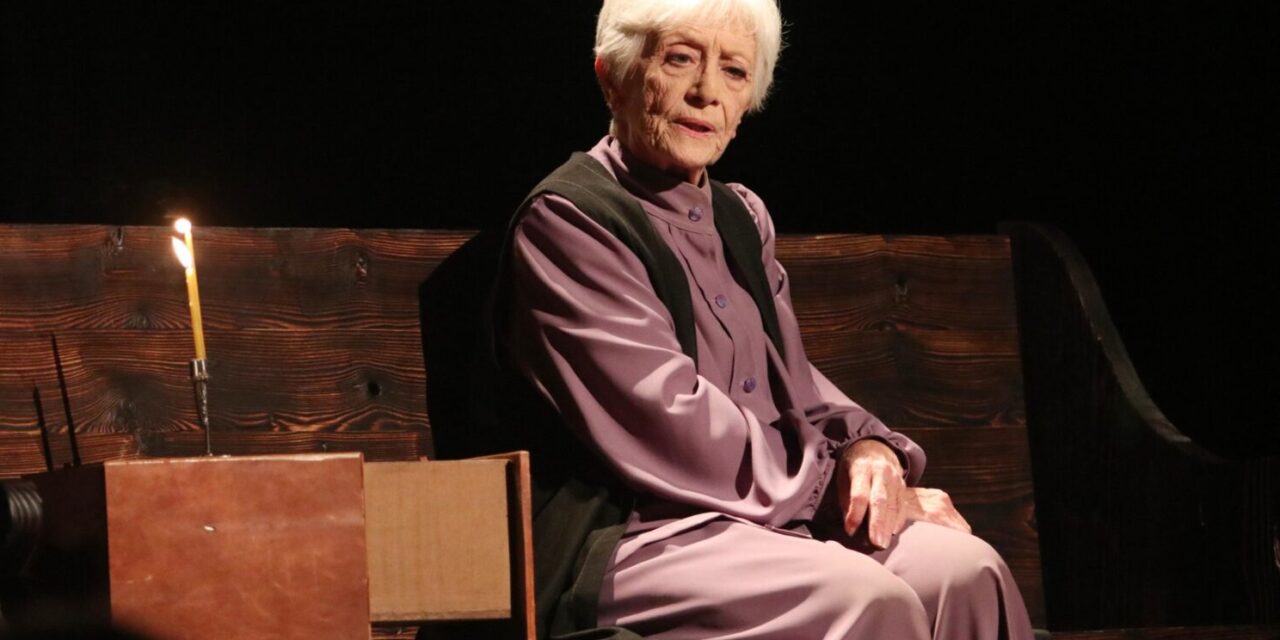

I was extremely fortunate to attend a performance that combined all of the above – Rose, written by the renowned Martin Sherman, with Despina Bebedeli, one of the greatest living Greek actresses, at Gialino Music Theater. In Rose, Sherman, after Bent, deals once more with the Holocaust. In this play, he creates a magnificent balance between the tragic historical events and the hopeful perspective of the narrator. Rose is a survivor. She is in her eighties when we meet her and shares with the audience the story of her life which began in a tiny Russian village, took her to Warsaw’s ghettos and a ship called The Exodus, and finally to the boardwalks of Atlantic City, the Arizona canyons, and salsa-flavored nights in Miami beach. The whole play is lightened by the use of humor, and the author’s political statements make it resonate as still very timely. The Greek translation by Mimi Denissi was very successful in transferring the spirit of the author and in preserving the rhythm and flow of the text.

I cannot imagine a more suitable protagonist for the part of Rose than Despina Bebedeli. The actress, almost the same age as Rose, from the very first minute, managed to capture our attention and kept us engaged until the last word of her monologue. Sitting on a bench, with minimal movement, she managed to act out the story by using every facial muscle, her expressive eyes, her hands and mostly her trained voice – a voice that, if you had your eyes closed, you could not believe it belongs to a woman of this age. Seventy-eight year-old Bebedeli seems to have no limitations. She can phrase long sentences in one breath, she sings beautifully, and she can manipulate colors and dynamics; her tone is clear and strong, and her stamina admirable. This is not surprising as she is one of the last tragediennes and has excelled in parts like Hecuba. Her acting is a real lesson for younger generations and can be used as an example not only for actors but also for classical singers who can learn from her what diction, inflection, and connotation is.

Twenty years following its premiere, Rose is a story that is, unfortunately, still relevant. Listening to it in Greek, by a woman who convinced us she could be the grandmother of us all, truly enhanced its global character.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Antigoni Gaitana.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.