It is not an easy prospect to adapt into opera one of the most acclaimed social realist novels of nineteenth-century Spain. Leopoldo Alas’s La Regenta was first published in two volumes in 1984 and 1885, and while it was not particularly revered in the writer’s lifetime, it has subsequently been acclaimed as a biting portrait of the petty concerns and vigilant culture of provincial society. There is something of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary in its tale of a young wife whose affair with a womaniser ultimately leads to social ostracism from the bourgeois society of which she is a part. The novel’s epic quality also evokes Anna Karenina and the piercing observation of the foibles and hypocrisies of the upwardly mobile middle classes further draws parallels with Dickens’ satirical prose novels.

Published by Penguin in an English translation by John Rutherford in 2002, La Regenta (which translates as “The Magistrate’s Wife”), focuses on the tale of a beautiful young woman, Ana Ozores married to a much older man, Víctor Quintanar, the retired magistrate of Vetusta (a fictional town that appears a mirror of the Asturian city of Oviedo). She wants to be a dutiful wife to a husband she cares for but less friendly interests in the town have other plans for her. The cathedral’s canon, Fermín de Pas, has his eye on her and she seeks fulfilment in religion, seeing him as a caring confessor and unaware of his controlling, sexual feelings for her. There is also the womanising Álvaro Mesía hovering in the distance who hopes to seduce her – Ana ultimately falling victim to two men who each want to control her whatever the consequences for the Magistrate’s wife. In the end, her confused husband, overly obsessed with reputational damage, is killed – he rashly challenged Álvaro to a duel that he loses. Rejected by the Church and Álvaro, Ana is shunned by the upper middle-class society that so wanted to see her fall.

What could have been a sprawling work is usefully contained in a chamber opera format configured sensibly not to compete with the novel. María Luisa Manchado’s score seeks to highlight the dissonance of a woman increasingly frustrated by the small-town gossip of Vetusta’s supposed great and good with a libretto from Amelia Valcárcel that posits the naïve Ana as an outsider in a town that expects everyone to tow the line. At the piece’s opening, a woman sits at the back of the stage in a petticoat, crying and clawing, clinging to the back wall and unable to pick herself up from the floor. The context has been set – Ana has been abandoned and rejected – what follows tells the audience how and why.

Urs Schönebaum’s sparse but effective set is a black box with a high balcony evoking separation between Ana and the community that seeks to manipulate her, as well as a pit or arena in which that same community can gleefully and voyeuristically observe the abuses perpetrated upon her. A sole chaise longue functions as the room’s only décor – an image of languor and social status for the Magistrate’s wife. María Miro’s mannequin-like Ana is always in that public arena, inside a vacuous doll’s house where she is often aggressively dressed like a doll by two maids. Her dresses — costumes are designed by Clara Peluffo — are tellingly those prepared for cut out paper dolls with the flaps to fold her into place still painfully visible. Ana is there to be manipulated and acted on, a passive presence, unengaged and separate who wants to please but finds herself unable to read the wider machinations going on around her. Vetusta’s “respectable” society stand on the balcony above her, always looking down at her, always observing her every move. The community which takes such pleasure from her plight are a motley crew, dressed in outfits from the seventeenth to the mid twentieth century, the production seems to be suggesting that not much has changed for the town’s inhabitants across three centuries. They work as a pack, pulling out umbrellas to give them height and at times to further distance themselves from Ana. The canon, his mother, and the womanising Álvaro all emerge from the balcony – all part of the society from which Ana can’t escape. They can walk away, Ana cannot.

The costumes provide a nod to the late nineteenth-century world of the original novel while playfully picking up references from both previous and later eras. Vicenç Esteve’s Álvaro Mesía sports a lilac jacket that evokes the classical cut of Casanova – his dainty steps and ability to creep up on Ana capture an elusive, self-obsessed and vain presence: he just wants to have fun. David Oller as Fermín captures the wooden awkwardness of a priest wracked with both guilt and a sexual desire he knows is wrong but cannot control.

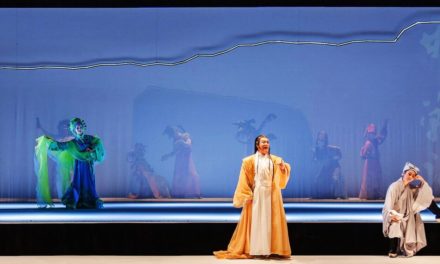

The provincial community maliciously watch the young wife Ana Ozores (María Miro) in La Regenta. Photo: Esmeralda Martín, courtesy of the Teatro Real

Bárbara Lluch’s staging is clean, focused, sensitive, and intelligent. Ana may be the piece’s protagonist but Lluch sensibly realises that she is a plaything, a trophy for her uneasy and emotionally distant husband, a source of entertainment for the bored town’s inhabitants, a toy for Álvaro and a weapon for the twisted Fermín. Sapo (the toad) here played by a skipping, impish green haired Gabriel Díaz who pops up across the action to laugh and scorn, ultimately drags the abandoned Ana across the floor – a reminder of her negligible worth in a town where appearances are all. The fact that she is tossed into a wheelbarrow on two occasions as if she were waste further accentuates this sense of her as a disposable commodity. There is a welcome feminist sensibility running through this sharp production.

Jordi Francés conducts the Orquesta Titular del Teatro Real energetically, propelling the sometimes-uneven score forward. The choral scoring undertaken by Manchado has a real charm, capturing the multiple controlling interests of a conservative community – the chorus of La Comunidad de Madrid is never less than impressive. Individual string writing was also strong with a tense pizzicato embodying the polarised relationships Ana has with the controlling community. I was particularly struck by the imaginative mix of piano and glockenspiel — the harsh, stark sound ringing across the pit. At the end, as Ana’s fall from society is complete, a violin solo by Vesselin Gellv plays, cutting lyrically through the silence, then vocalised beautifully by María Miro’s humiliated Ana to poignantly close this biting new chamber opera.

La Regenta, co-produced by the Teatro Real and the Teatro Español. at the Sala Fernando Arrabal, Naves Español en Matadero from 24-29 October 2023.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.