“You into words?” Jamie Lloyd’s magnificent treatment of Cyrano de Bergerac very much is. Refracted through Lloyd’s modestly masterful staging, Martin Crimp’s vigorous, insightful adaptation of Edmond Rostand’s 1897 play becomes a searing meditation on language and desire. Sure, the same concerns are already at the forefront of the original play, but Crimp’s version takes things up a notch by burrowing deep into the characters’ psyches and unearthing what it finds there through playfully lucid poetry.

Cyrano de Bergerac flows through its three-hour run like butter melting in a frying pan. This is not only because much of it is in rhyming verse, but also because the cast—led by a magnetic James McAvoy—has an exceptionally muscular grip on the play’s language. It still tells a somewhat bizarre story—but one that feels charmingly convincing in this production: Cyrano, the legendary poet/soldier with a legendary nose, sublimates his love for the beautiful Roxane by helping the tongue-tied Christian woo her. As the courtship blossoms through a series of dazzling love letters written by Cyrano, the swashbuckling hero must decide how far he is willing to take this game—and whether he will ever come clean.

This romantic tale unfolds in a world where contrasting currents are in harmonious contact. On the one hand, Lloyd’s production has a vaguely contemporary ring to it: The actors are dressed in tracksuits, down jackets, and overalls. Vaneeka Dadhria’s live beatboxing creates the soundscape. Soutra Gilmour’s set consists of a svelte wooden box with a few chairs and microphone stands. The language exudes a fresh, modern-day tinge. On the other hand, Crimp’s re-write preserves the work’s original setting—France, 1640—and keeps many of the period-specific allusions intact, while slightly adjusting the others. Cyrano’s oversized nose is still an indispensable element of the play, but this production is so at peace with its stripped-down aesthetic that McAvoy does not wear any prosthetics or makeup on his nose. Crimp’s precise language is sufficient by itself to conjure vividly the notorious nose that drives the story to its extremes.

Fittingly, we are in a world where quick-witted eloquence serves as the greatest currency, where men rise and fall by how elegantly their speech rhymes. Rap battles and spoken word performances are the settings in which Cyrano’s ripostes and repartees take flight. He frowns upon prose and glorifies rhyming verse. Swinging a microphone and writhing to the sound of beatboxing, he “kills” someone using poetry. But Crimp’s text is also interested in going from poetry to poetics, asking why its characters are obsessed with their locution. There are reflective moments when Cyrano defends his creative autonomy against potential patronage when the risk of having his free speech smothered by censorship feels more high-stakes than an impending war. This Cyrano ends up being at once a celebration of language and an elegy for its limits.

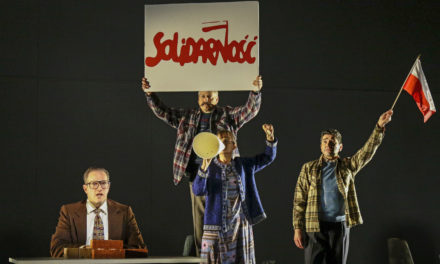

The cast of Cyrano de Bergerac at the Playhouse Theatre. Photo: Marc Brenner

James McAvoy’s soulful, electrifying performance gives the production its pliant backbone. His emotional range is stunningly wide: one moment his face is twitching with self-confident excitement, and the next he is delivering a deadpan (but deeply felt) speech that turns Roxane on. It is an expertly modulated rendering that takes McAvoy to some unexpected, dark places. His Cyrano is intensely sympathetic, but not cloying or melodramatic. There is a calm about him that represses an abundance of tempestuous feelings while offering a glimpse of them.

Crimp’s version endows Roxane with admirable depth and a distinctive wit of her own, peppering the play with probing interjections about her agency in the narrative. Anita-Joy Uwajeh’s pitch-perfect performance taps into these flourishes with great gusto. As Christian, Eben Figueiredo displays a pleasingly edgy demeanor, and his portrayal of the character’s final moments is charged with unanticipated nuance. There are memorably strong supporting performances, too: Michele Austin transforms the poet-cum-baker Ragueneau into a maternal mentor to Cyrano, and Tom Edden’s De Guiche is a vividly imagined antagonist. The ensemble’s cohesive work draws much strength from Polly Bennett’s discreetly stylish movement direction.

Powered by these captivating performances, Cyrano charts a vast tonal landscape. The first three acts’ breathtaking rhythm and rapier-sharp humor are radically abandoned after the interval, when the characters are plunged into an exacting war. Past this point, Lloyd’s staging takes such a static and dim turn that one would expect it to fall flat, but it doesn’t: it just rears up in a different register. The final scene, in particular, is shatteringly effective in its stagnancy. Crimp broods upon and elongates Rostand’s concluding moments, picking them apart from both Roxane’s and Cyrano’s perspectives, and leaving us with a gut-wrenching tableau.

Lloyd and Crimp have clearly dug deep, deep into Rostand’s play and revamped it with strategic elegance, not to mention panache. It may not have a stupendous nose, but their Cyrano is definitely one to behold and admire.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mert Dilek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.