There are plenty of theatre translators who start out as actors, directors, playwrights or other practitioners. Happening to have a second language, they move into translation as an extension of their creativity. Coming to theatre translation ‘from the inside’ – from inside theatre, that is – they enjoy a certain advantage both in terms of what networks they may already have in the theatre industry and insofar as they already have a handle on theatrical language and the way in which a piece of theatre is created.

But what of translators coming from the other direction? What of the professional translators who would like to move into translating plays but whose background lies in translating other types of text? These translators, who can often be well-qualified, well versed in theory, and highly experienced professionals in their own right, can find it difficult to be accepted into the arena of theatre. An assumption that such translators are not able to handle dialogue that is to be spoken by actors can lead to opportunities being scarce. Furthermore, these translators can themselves feel unable to tackle theatre texts precisely for the lack of such experience.

I have remarked on a number of previous occasions, including in this recent article for Words without Borders, that exacerbating this problem is the fact that there are no ‘safe spaces’ for theatre translators to hone their craft. In the UK, theatre scarcely features in translation training, and likewise there are no vocational theatre courses where translation is an option as a specialism. Translators who are interested in theatre but who do not happen to be theatre practitioners are left with no option but just to try it out and hope for the best.For the more widely spoken languages, perhaps this is not too great a problem. Given the relatively small amount of translated theatre that is produced in the English-speaking countries, there may well be enough Spanish- or French-to-English actors-turned-translators to go around. But aside from this survival-of-the-stagiest state of affairs seeming somewhat harsh on other budding theatre translators of these more common languages, it also leads to there being a tiny or non-existent pool of translators from the less widely spoken languages, with the result that access to good, rehearsal-ready translations of plays from, say, Georgian or Thai, is greatly reduced. For both ethical and practical reasons, then, I have often regretted the absence of any kind of practice-focussed environment for existing translators to develop specifically as translators of theatrical texts.

Fortunately, one theatre company in East London is setting out to change this.

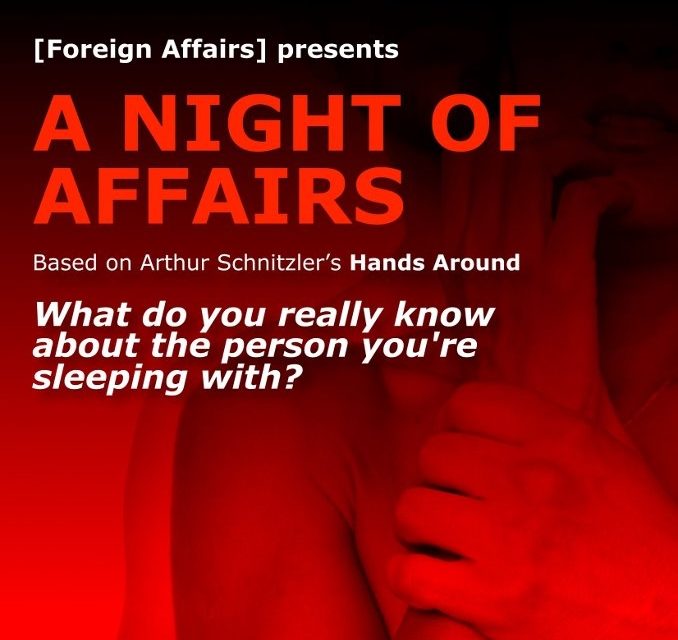

Established in 2010 by co-artistic directors Trine Garrett and Camila França, [Foreign Affairs] has since its inception been a vocally international company with ‘a focus on pushing artistic, social and creative boundaries through translation, ensemble work and performance in unconventional venues.’ Its founding ideal, ‘to cultivate a creative environment in which people from all walks of life can come together to explore work and develop new and exciting ideas to share with the world’, has led to collaborative projects with theatre makers from throughout the world, most recently in productions of Danish playwright Jakob Weis’s Helmer Hardcore, translated by Paul Russell Garrett, and, in collaboration with the University of Cambridge, of Arthur Schnitzler’s Professor Bernhardi.

Recognising the absence of opportunities for translators to move into the realm of theatre from without, Garrett and França conceived ‘[Foreign Affairs] Translates!’, a bespoke, practice-based training programme aimed at translators from any language wanting to try their hand at translating plays. In its inaugural year, applications were opened in Spring 2016, with translators invited to present a theatre translation project to be worked on during the programme.

Aside from the requirement to translate into English, no limits were set on the background of the translators: no previous theatre experience was required and translators for whom English was not a first language were also welcome. Plays from any language and any genre were accepted.

‘As a theatre company we aim to bring people together through shared stories from our neighbours around the world that can inspire, enlighten and engage. In a cultural landscape where the Brexit decision has only highlighted the need for tolerance, understanding and empathy we continue to cultivate a space to promote multicultural exchange and dialogue.’ Trine Garrett – Co-Artistic Director [Foreign Affairs]

For this pilot year, three applicants were selected, working from Swedish, Hungarian and Croatian. Siân Mackie translates August Strindberg’s To Damascus, a surprisingly comic exploration of solitude and nihilism with uncanny resonances for our modern-day ‘age of loneliness’; Jozefina Komporaly translates András Viksy’s The Unburied. The Saint of Darkness, a reimagining of the life story of Mother Teresa and the Antigone myth with a contemporary eye on the unburied bodies of 21st Century geopolitics, and Valentina Marconi translates Zlatko Sviben’s stage adaptation of Ivana Šojat’s novel Unterstadt, a family saga tracing a German-origin family through the turbulence of the Croatian 20th century.

The translators were engaged in a series of readings, practical workshops, and one-to-one mentoring sessions to support them in the translation of their plays as texts to be embodied and voice by actors.

As one of the mentors, along with Roland Glasser and Paul Russell Garrett, I was delighted to be involved in this important work. It is rare for a translator to have such detailed and supportive attention paid to him or her in the creation of a translation. The workshops included several sessions where the various drafts were read by a group of actors, allowing the translators to hear their work spoken and acted and also to receive feedback from the company without this feedback coming in the pressured and often implicitly hierarchical environment of a rehearsal room. Another workshop involved the translators, mentors, actors and [Foreign Affairs] creative team participating altogether in sessions exploring practically how the words in a scene from a play can be interpreted into movement, music or emotion. And the one-to-one mentoring sessions allowed for extended, detailed conversations about their work.

What has struck me as powerful in this process is the absence of any particular ideology or methodology in the translation process. Sharing in the development of three translations of three very different plays by three very different translators, I have become even more convinced of the importance of matching the translation process to the play and not vice-versa. Rather than being seen as ‘representative’ of Sweden, Croatia and Hungary/Romania, of these countries’ cultures or, somehow, of the source languages themselves, the translations have focussed instead on the plays as individual works. Similarly, rather than prioritising notions such as ‘speakability’ – which is bound up with naturalism and may not be a useful concept for works from other genres – space has been given for a detailed exploration, again, of what target-language options are available stylistically, and which ones may best match the translator-translated text partnership.

Once again, this kind of breathing space is extremely rare, especially when initiated not by an academic or literary organisation, but by a theatre company. We were able to tackle questions which, in other contexts, could be left to the translator to handle alone or addressed hurriedly and unsatisfactorily in an already under-way rehearsal process, by which time other production pressures may find themselves taking precedence.

The outcome has been that the translations that [Foreign Affairs] will be sharing at London’s Arts Theatre on December 9 and 10 are bespoke, original creations that, while still ‘faithful’ insofar as they remain translations (rather than moving into the realm of adaptation), are the result of a detailed – and, crucially, facilitated and supported – creative journey based on the translators’ responses to the individual plays.

Following this year’s pilot programme, [Foreign Affairs] intends to continue running [Foreign Affairs] Translates! into 2017 and beyond.

‘Working with these three incredible female translators has been a privilege and a joy. We are proud that [Foreign Affairs] Translates! has had such a positive and demonstrable impact on the process of these plays being translated into English. By helping the translated words move from page to stage in such a vital way we feel we have truly helped these non-English language plays to gain a stronger voice. We are thrilled by the feedback this pilot programme has received from both the translators and the academic and the theatre community, and will be taking this forward as we look to secure funding and expand the programme in 2017 and beyond.’ Camila França – Co-Artistic Director [Foreign Affairs]

I certainly hope it does. If theatre translation in the English-speaking world is to reach its full potential, and if, as a result, theatre producers are to have better access to high-quality translations of plays from throughout the world, this cannot be achieved unless translators, whatever their background, have more spaces like this in which to develop their skills.

The [Foreign Affairs] Translates! showcase takes place Above the Arts in London at 7:30pm on Friday 9 and Saturday 10 December 2016, with a post-show panel discussion on both nights. Tickets can be booked at the Arts Theatre online.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by William Gregory.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

![[Foreign Affairs]. Photo by Cameron Slater Photography](https://thetheatretimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/15388627_10153999016177341_1012167683_o-1024x512.jpg)