It is almost impossible to describe the experience of seeing the work of the legendary Polish director Krystian Lupa. Imagine a trance-induced theatrical experiment that draws you into a bottomless abyss insidiously. Lupa chisels an unimaginable territory that you wouldn’t even dare or be able to dream in your deepest slumber. The way Lupa’s actors speak and move on the stage is reminiscent of a broken phonograph that repeats unspeakable horrors of humanity in a monotonous, indifferent tone. Nothing is dramatized or emphasized. Lupa’s dramaturgy visualizes a flat terrain without horizons. Characters wander on this barren land, aimlessly but desperately, with lava boiling and roaring underneath yet invisible and inaudible.

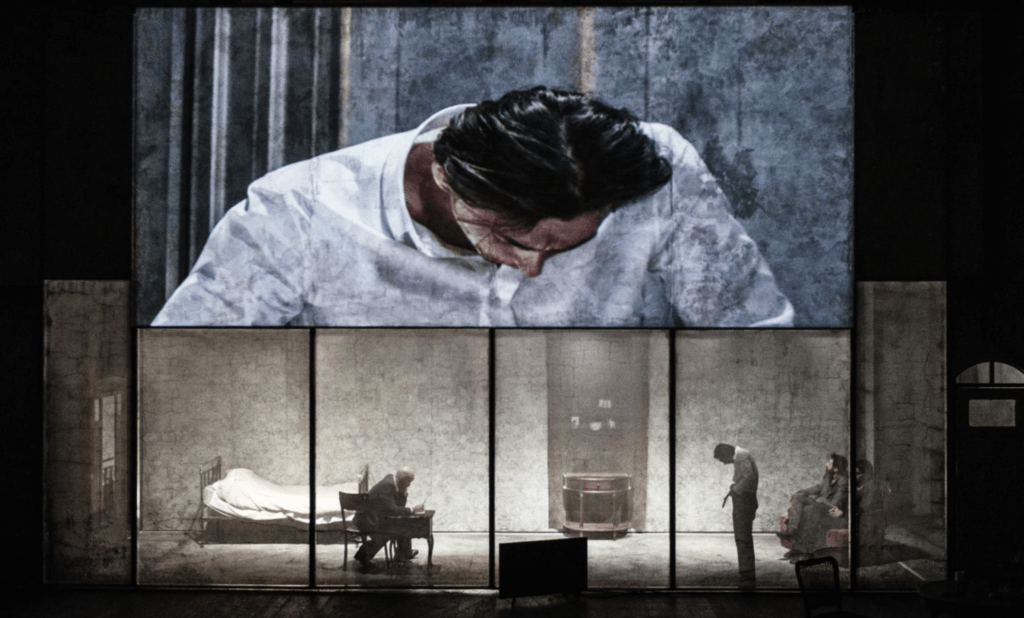

The Trial, directed by Krystian Lupa, Divine Comedy Festival 2017, Teatr Łaźnia Nowa—Duża Scena, Photo credit: Magda Heuckel

Franz Kafka thus couldn’t find a better suitor than Lupa to envision his 1914 novel The Trial on the stage; it recounts the bizarre, incomplete and horrifying story of a man, Josef K., who is arrested and prosecuted by an invisible authority for unknown reasons. The production, which was supposed to premiere at Teatr Polski in Wrocław in 2015, was interrupted and postponed by Lupa in protest against the scandalous appointment of the theatre’s new artistic director, Cezary Morawski, by the Minister of Culture. Lupa resumed rehearsals a year after, and this 7-hour epic rendition finally premiered at the Old Theatre (Stary Teatr) in Krakow.

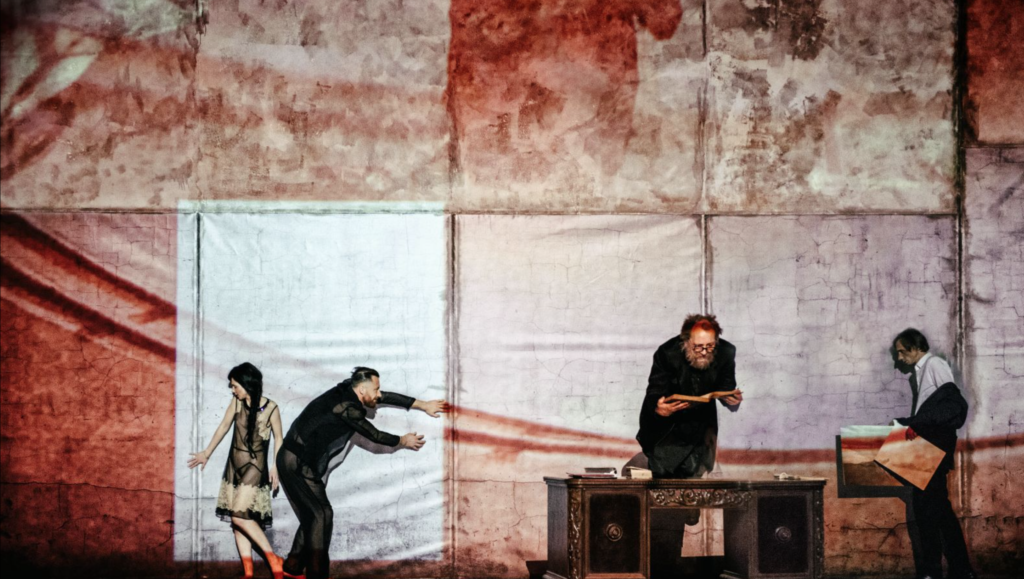

The Trial, directed by Krystian Lupa, Divine Comedy Festival 2017, Teatr Łaźnia Nowa—Duża Scena, Photo credit: Magda Heuckel

Lupa’s adaptation of The Trial, therefore, gains a specific meaning in the context of Polish theatre’s crisis: the increasing intervention of government and various forms of censorship under the conservative party. The hopelessness and desperation of the protagonist K. in the face of absolute yet veiled power are what many theatre artists are experiencing in Poland. Lupa’s Trial puts audiences in the seats of the prosecutor, witnessing the human bodies and souls decay on stage. Almost unbearable to watch is the end of the second part of the show, where actors are lying on hospital beds for almost two hours. K., played by the phenomenal Andrzej Kłak, sickens and decomposes in a prolonged and brutal manner in front of us. He is humiliated, stripped and attired in dresses by an actress as if he were a doll. Wholly eviscerated, K. cannot find his way out of the impossible labyrinth of the Law. Then, a character reminds us that we’re in 2017, and tells a story (allegedly written by Kafka) of a man burned alive at a central square. It is impossible not to relate this story to the tragedy of the 54-year-old chemist Piotr Szczesny, who, in protest against the new government, set himself on fire in front of the monumental Palace of Culture in Warsaw and died shortly after. The sheer contrast between Piotr S.’s extreme action and Lupa’s paralyzed and plagued actors on stage suggests the lack of response and the overwhelming feeling of artistic homelessness that many Polish actors are experiencing now.

The Trial, directed by Krystian Lupa, Divine Comedy Festival 2017, Teatr Łaźnia Nowa—Duża Scena, Photo credit: Magda Heuckel

“Modern business-people and lawyers are, in fact, powerful sorcerers. The principal difference between them and tribal shamans is that modern lawyers tell far stranger tales.” Yuval Noah Harari’s words summarize the absurdity and cruelty of invented laws depicted in Kafka’s The Trial. We thought we had passed the time of kings and queens, or the mysterious power used to dominate us. Yet there are far stronger and stranger powers that control and regulate our bodies and minds. Except this time they are invisible and untouchable. After all, storytelling is what makes human beings powerful but also destructive. At the end of Lupa’s eerie adaptation, a character simply says, “You know what happens next.” People who are familiar with the novel immediately experience the final scene of K. being stabbed in the heart and his final words “Like a dog!” reenacted and resonating in their imaginations. We don’t need to see it to know what happens next. Just like we don’t need to know the reasons before we sentence someone.

A special report on Divine Comedy Festival was prepared with support of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute – the national institution of the culture of Poland. To learn more about polish theatre go to http://culture.pl/en/category/performance

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kai-Chieh Tu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.