Quantum’s marketing slogan for this season is “theater that moves you,” and its production of King Lear delivers on all of the meanings of that phrase. Let’s start with the most prosaic: it’s actually going to make you move, first and foremost to the fabulous site of the former Carrie Blast Furnace, which I’m willing to venture will be a new discovery for more than a few of you dear Readers. Monumental, massive, and stunning in its decay, the Carrie Furnace is a place that is uniquely Pittsburgh, testifying both to the ambitions and achievements of the city’s past leaders and to the transience of its once-powerful steel industry.

In other words, it’s a perfect backdrop for the story of Lear, who likewise finds his power and status hollowed out over the course of the action. Scenic designer Tony Ferrieri puts the crumbling infrastructure of the former steelworks to breathtakingly beautiful use in telling Lear’s story. The first act uses the gargantuan architecture of iron pipes, stairways, and platforms as part of the set, with a throne fashioned out of a cairn of flat stones in the foreground lending the production a mythic Stonehenge-meets-Steampunk vibe. For the second act, you have to move again, this time on a quarter-mile journey through the site’s desolate landscape – along a path lined with paper lanterns – to a pastoral ring on the periphery that is enclosed with corrugated steel walls. Here, Ferrieri and lighting designer C. Todd Brown make the ghosts of Pittsburgh’s industrial past stand-in for Lear’s diminished sovereignty: the brightly-lit furnace looms majestically behind the audience seating while three enormous shrouded steel monoliths stand silent sentry in the background of the action on stage.

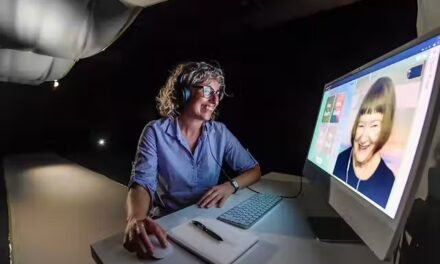

L to R: Dana Hardy, Connor McCanlus, Catherine Gowl, Jeffrey Carpenter, Ken Bolden, Lissa Brennan, Monteze Freeland, and Michaelangelo Turner; at the Carrie Furnaces National Historic Landmark Site, courtesy of Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area. Photo by Heather Mull, courtesy Quantum Theatre.

The long trek from the site of the first act to the site of the second is no mere gimmick – it echoes the trajectory of the action. Act one of this version of the play – which has been judiciously edited by James Kincaid and Julian Markels – ends with Lear, Kent, Gloucester, and Edgar all having been cast out into the wilderness and headed toward Dover. Act two draws them, and us, to Dover for the play’s tragic resolution. Their journey is our journey, and it felt right to have to walk a distance in the dark through a strange and disorienting terrain as a way of marking the passage of time in the play’s action.

Of all the site-specific Quantum productions I’ve seen over the years, this may be the one that has best married site to play and integrated all of the design elements into an eloquent world. Echoing the aesthetic of the set, Susan Tsu’s elaborately layered costumes pull from both the medieval world and the protective clothing of the early twentieth-century steelworker. Handknit cowls and belted leather jerkins are accessorized by protective goggles, hardhats, and welder’s masks, effectively ghosting the spirit of Pittsburgh’s former grandeur into Lear’s loss of his dominion. The costuming coup de grace, however, is a massive, detailed topographical map of England that serves as Lear’s cape in the opening scene, replete with such features as the mountains of Cumbria and the white cliffs of Dover. Steve Shapiro’s ominous, rumbling sound design seamlessly integrates the soundscape of the surrounding area into the production, such that there are times when the crescendo and decrescendo of a passing freight train seems to be coming from the surrounding speakers rather than the nearby tracks. As the sun sets, Brown’s lighting gives added depth and dimension to the complicated architecture of the site and effectively establishes both the frenzy of the storm in the first act and the placidity of the pastoral setting in the second.

This production of Lear won’t just make you physically move; it is also extraordinarily moving, thanks largely to Jeffrey Carpenter’s nuanced and sensitive handling of the main role. Shakespeare gives Lear a lot of ranting and raving to do in this play – the guy is betrayed and then gaslit by his thankless, greedy daughters, after all – but Carpenter gives Lear’s anger and madness modulation and shape, punctuating big outbursts of rage with moments of quiet tenderness and baffled self-reflection. In the first act, Lear’s primary relationship is with the Fool, played with cheeky bravado by a southern-accented Tami Dixon in longjohns and a hardhat. In the second act, that place is taken by his banished daughter Cordelia (Catherine Gowl), and the scene in which he struggles to recognize her when they finally meet again is exquisitely poignant, importing a modern understanding of the confusion of dementia into Shakespeare’s depiction of “madness.”

Jeffrey Carpenter and Catherine Gowl. Photo by Heather Mull, courtesy Quantum Theatre.

Also deeply stirring is Connor McCanlus’s portrayal of Edgar, who is framed as a would-be patricide by his half-brother Edmund (a role given unexpected complexity and depth by Joseph McGranaghan). McCanlus’s Edgar first appears as a louche child of privilege, nonchalantly smoking a cigarette and oblivious to his brother’s power-hungry machinations. His decision to feign madness after Edmund’s plot succeeds shows him to be a coward at heart, and as the play proceeds from there, McCanlus beautifully tracks Edgar’s slow and uneven evolution into the courageous son who finally comes to avenge the wrong done to his father Gloucester (Ken Bolden) and himself.

As Lear’s fiercely loyal counselor Kent, the magnificent and majestic Monteze Freeland anchors the play’s moral center while also keeping the storytelling on track with crystal clear delivery of much of the play’s exposition. Rounding out the strong ensemble are Lissa Brennan as Goneril, Dana Hardy as Regan, Jessie Wray Goodman as Oswald, and Michaelangelo Turner as the good Duke Albany.

Director Risher Reddick, who is new to the Pittsburgh theater scene, has shaped the story of the play with lucidity: so clear are the actors’ intentions and actions that shortly after the play begins, you no longer feel that you are listening to Shakespearean language (which may well be the highest praise one can heap on a production of a Shakespeare play). Riddick has added songs that frame and contextualize the action, and has used staging adeptly to establish character status and effect transitions between the many locales called for by the story. A few of the staging choices are more puzzling than enlightening – for example, I wasn’t sure what to make of the group of welding-masked people warming themselves by a fire in the storm scene – but overall his directorial choices serve to bring the heart of this tragedy to the fore through vivid stage pictures and a strong emphasis on the emotional journeys of the characters.

So stirring and captivating are the final scenes of this production that when the (ahem) “atmospheric mist” started to fall midway through the second act on the night I saw the show, guess what? No one in the audience moved.

This article was originally posted in The Pittsburgh Tatler on 15 May 2019 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Wendy Arons.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.