To celebrate its 35th anniversary, the internationally renowned Kodo drumming troupe staged three days of performances at Tokyo’s Suntory Hall in mid-August, with a different theme for each show.

On the first night, Kodo played together with the New Japan Philharmonic; on the second, the troupe showcased its latest, musically nuanced program, Rasen (Spiral); while the closer featured a collaboration with two contemporary-dance companies — the theatrically inclined Dazzle and the acrobatically stunning Blue Tokyo.

The whole event, which was comprised of wadaiko (traditional Japanese drumming), music and dance, pressed all the right buttons for a wide range of performing arts fans. However, it also displayed the creative direction Kodo has taken after the troupe began being fostered by its artistic director since 2012 — the 66-year-old kabuki onnagata (a male actor specializing in female roles) Bando Tamasaburo V.

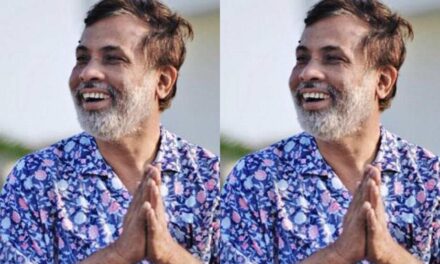

Artistic direction: Kabuki star Bando Tamasaburo V believes Kodo needs to expand beyond just drumming to capture a greater share of the global audience. | © TAKASHI OKAMOTO

Originally a spinoff from Ondekoza, a troupe founded in 1969 that was a pioneer in extending wadaiko’s reach from local festivals to theaters nationwide, Kodo made its well-received debut at the Berlin Festival in 1981.

There were just a few hundred wadaiko and kumi-daiko (theatrical drum-performance) troupes in Japan when Kodo started, but there are now around 5,000 — with some performing overseas as well. However, Kodo is a major force among them. The company has toured consistently since it began, showing the world its trademark local-festival style of dressing the drummers in happi coats and hachimaki headbands as they beat their taikodrums with bachi (thick drumsticks) in synchronized barrages of sound. This has become the epitome of wadaiko in many people’s minds.

In 2000, however, Kodo was shaken from its seemingly settled position following a fateful encounter with destiny in the person of Tamasaburo. Back then — unheard of in either the wadaiko or kabuki worlds—the famed actor was invited to join the troupe at its Kodo Village base on Sado Island in Niigata Prefecture to direct a new program titled The Kodo One-Earth Tour Special, which premiered in 2003. That invitation, it transpired, was the result of a strategic decision by Takao Aoki, the troupe’s managing director, to set Kodo on a new course away from the one that had become something of a stereotype.

Planning a set: Bando Tamasaburo V joins members of the Kodo drum troupe for a rehearsal at its base on Sado Island in Niigata Prefecture. | © TAKASHI OKAMOTO

When Tamasaburo’s fresh approach with One-Earth — a production that stressed the exquisite over the dynamic, with drummers wearing jeans — was a hit with critics and audiences alike, it was clear that Aoki’s instinct had not failed him.

Next came Amaterasu, a 2006 music-dance piece created by Tamasaburo that took its title from the name of the ancient Sun Goddess of Japan — and in which the kabuki actor performed for the first time with Kodo.

More coproductions then followed before Kodo decided their courtship was over and it was time, in 2012, to officially make Tamasaburo the troupe’s artistic director and entrust its future to him.

They bang the drums: Drummer Masayuki Sakamoto (left) and Kodo Ensemble Leader Yuichiro Funabashi are currently touring Rasen (Spiral) across Japan. | NOBUKO TANAKA

“As they are percussionists and musicians, not just exclusively wadaiko players,” Tamasaburo tells The Japan Times, “I believed they could be more expansive and rise to the challenge of expanding their ability to express their own world. I didn’t want to see them remain narrowly slotted into a limited wadaiko category.”

Going on to talk about his artistic policy and his thoughts on refashioning Kodo for rising generations, he continues, “If we were still in something like the 1980s bubble economy time, when people had plenty of money to spend, the entertainment world wouldn’t need to worry much about filling their theaters’ seats. However, times have changed and far fewer people spend money going to theaters now, so the range of viable performing arts has narrowed.

“Accordingly, to reach out to more than just fans of traditional wadaiko, Kodo needs lots of variety in its repertoire to suit different audiences and occasions — some material for showy festival stages and some for top-class concert halls.

“If it had stayed wedded to its traditional formula, Kodo would have been deadlocked and would have really struggled to survive in today’s competitive world, which is saturated with recreational opportunities.”

When he was appointed as the company’s artistic director, Tamasaburo gave himself a target to create programs without using popular taiko folk numbers such as “Oodaiko” (“Big Drum”), “Yataibayashi” (“Festival Music of Drums on Trolleys”) and “Miyake” (an island in the Izu chain) that had been at the core of its shows.

Instead, he worked with all the members to put together a new set list of original numbers — some by modern classical music composers such as Isao Tomita and Maki Ishii, others by Kodo’s drummers and the artistic director himself.

Since 2013, all the shows have drawn from that new material. Thanks to Tamasaburo, they have also featured highly visual sets and stylish costumes — including a huge snake puppet in that year’s “Shinpi” (“Mystery”).

“To widen their musical scope, I thought I needed to force them apart from the familiar set list,” Tamasaburo explains. “I never said I wanted to eliminate those traditional numbers forever, but bold steps have been necessary to change their long-term practices.

“To be honest, though, it’s quite hard to create colorful variations every year, because Kodo is a percussion troupe, not a full-scale orchestra. So that was exactly why I asked them to adopt different ways of expression, including getting their drums to sing and whisper, rather than just bashing them hard.”

Kodo ensemble leader Yuichiro Funabashi, 42, and core member Masayuki Sakamoto, 32, think the August event was a success and a great chance for the troupe to unite before advancing to the next stage.

“The new program, Rasen, draws on our heritage of old traditional taiko pieces and integrates them with modern numbers so they naturally blend together and become up-to-date music,” Funabashi says.

Lead spot: Yuichiro Funabashi, 42, says he’ll never forget what Bando Tamasaburo V once told his Kodo drum troupe: “Artists are finished as artists when they forget humility.” | © TAKASHI OKAMOTO

Sakamoto elaborates, saying, “The title, Rasen, suggests how the program contains old and new numbers rising and whirling together as our methods of expression have changed dramatically to have more depth and refinement… I’m full of excitement about a world in which it becomes common for people to play Western and other instruments and Japanese drums together and create music like nothing ever heard before.”

Funabashi recalls something Tamasaburo told them — “Artists are finished as artists when they forget humility” — before commenting, “When I heard those words I was young, so I just nodded, but I now feel the reality of them much more. Actually, Tamasaburo has always been so humble in himself, and he’s humble regarding his own creations, too. He’s never satisfied and is always thinking and questing for further possibilities. I always keep in mind his humility toward art.”

Whirl of ideas: Kodo drummer Masayuki Sakamoto says the title of the troupe’s latest production, Rasen (Spiral), is meant to represent the swirling together of ideas that have defined Kodo in the past and will be a part of its future. | © TAKASHI OKAMOTO

Tamasaburo believes that Kodo can’t survive just as a troupe of Japanese drummers.

“If audiences overseas are only fascinated to see them because of their uniqueness, they won’t come back again,” he says. “So I want them to be world-class percussionists and stage performers and real artists who are also comfortable with European music so they can fill up any kind of venue, thanks to their musical quality.

“But being real artists, that’s the first priority. It’s the same in the world of kabuki.”

Drum row: Members of the Kodo drum troupe will tour latest production Spiral across the country through late December. | © TAKASHI OKAMOTO

This post originally appeared on The Japan Times on September 22, 2016, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.